OLIVER WAKE

With his 1956 play Look Back in Anger, John Osborne (1929-1994) famously kick-started the theatrical trend for “Angry Young Men” and drama which explored the grimmer side of contemporary life, putting society’s discontents centre-stage. Amongst a body of further stage plays, Osborne also produced a clutch of screenplays for cinema and, more pertinently for us, television.

Television had played a modest part in the success of Look Back in Anger. The play was at break-even point when an extract was broadcast from the Royal Court theatre by the BBC close to the end of its run.1 Following this exposure, the rest of the run sold out and the play was transferred to the Lyric theatre to meet excess demand.2 Six weeks after the excerpt was televised, the full play was broadcast by Granada, directed by its theatre director Tony Richardson. Writing in The Manchester Guardian, Bernard Levin found that the play made “tremendous television.”3 Look Back in Anger was produced for television in Britain again twice, by the BBC in 1976, to mark the play’s twentieth anniversary, and as an ITV/Channel 4 co-production of Judi Dench’s stage version in 1989.4 Extracts were also performed in two episodes of The Present Stage, ABC’s 1966 series exploring modern drama.5

Continue reading “John Osborne”

Look Back in Anger, BBC, tx. 16 October 1956. ↩

The effect of the televised extract is detailed in John Russell Taylor, Anger and after: A Guide to the New British Drama, Revised edition (London: Methuen, 1969), p. 35, amongst many other sources. For further information, including how the impact of the televised extract has been exaggerated, see John Wyver’s fascinating post ‘From the ’50s: Look Back in Anger (BBC and ITV, 1956)’ on the Screenplays blog (posted 30 June 2013), available here. ↩

Bernard Levin, ‘Truth Duller Than Fiction’, The Manchester Guardian, 1 December 1956, p. 5. ↩

Play of the Month: ‘Look Back in Anger’, BBC1, tx. 21 November 1976; Look Back in Anger, ITV, tx. 10 August 1989. ↩

The Present Stage: ‘Look Back in Anger’ (1 & 2), ITV, tx. 17 and 24 April 1966. ↩

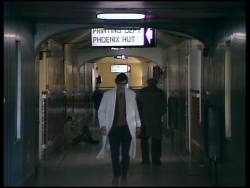

Funny Farm depicts a night shift by nurse Alan Welbeck (Tim Preece) on a psychiatric ward. As reviewer James Scott put it, the play comments on “conditions in our mental hospitals – understaffing, overwork, bad pay, old inadequate buildings” and unsatisfactory “patient treatment and cure”, points which are heightened by the play’s “understatement” and rejection of “sensationalism and sentimentality”.

Funny Farm depicts a night shift by nurse Alan Welbeck (Tim Preece) on a psychiatric ward. As reviewer James Scott put it, the play comments on “conditions in our mental hospitals – understaffing, overwork, bad pay, old inadequate buildings” and unsatisfactory “patient treatment and cure”, points which are heightened by the play’s “understatement” and rejection of “sensationalism and sentimentality”.