by FRANK COLLINS

Writer: David Leland; Producer: Margaret Matheson; Directors: Mike Newell, Edward Bennett, Jane Howell, Alan Clarke

Because this site’s editor, Dave Rolinson, was involved with the Tales Out of School DVD (writing its 12,000-word booklet), it seemed fairer to ask a guest writer to review it: so here’s a review by Frank Collins, who writes the excellent, highly-recommended film & TV review blog Cathode Ray Tube. Many thanks to Frank for letting us reproduce this review.

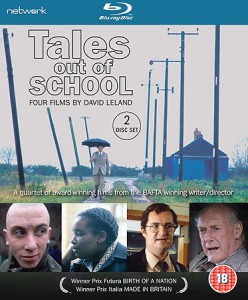

David Leland’s quartet of dramas from 1983, under their original umbrella title of Tales Out of School, gets a very welcome release from Network this month. All four films, Birth of a Nation, Flying into the Wind, RHINO and Made in Britain, were commissioned by Central Independent Television, the ITV franchise that emerged from the restructuring of the original ATV, and were produced by Margaret Matheson, who had become Controller of Drama after a successful if controversial time at the BBC where she had produced Alan Clarke’s banned television play, Scum. After a steady career as an actor during the 1960s and 1970s, Leland’s reputation as a writer willing to tackle socially sensitive subject matters grew through his work in 1981 on Play For Today, on Psy Warriors and Beloved Enemy.

Both plays had also brought him into contact with director Alan Clarke whose work, radical and realist in tone, had become fiercely political and controversial (he had directed the banned production of Scum for Matheson and the later cinema version). Their paths would all cross again on the production of these four films, with Clarke directing the Prix Italia award-winning Made in Britain, the final film of the quartet. As Leland outlines in both of the excellent documentaries that supplement this release, he had been concerned with the structure and power of mass education for some time.

Tales Out of School firmly belongs in the tradition of social realist drama that stretches back to the work of Loach, Garnett and Sandford on Cathy Come Home in 1966, and was contemporaneously in 1982, in what was seen as a very politically and socially divisive period, perhaps then exemplified by Bleasdale’s recent Boys from the Blackstuff. In his four films Leland traces a number of still contentious ideas about education, questioning the institutional roles and teaching practices within schools, the power of the education system, the law and the judges and courts that dispense order and structure within a complex web of relationships between pupils, teachers, parents, education officers, the police, magistrates and social workers. By doing so he asks us to consider how these institutions, and schools particularly in the first two films, shape the futures of young people, perhaps through a repressive and conformist curriculum that is more concerned with processing young minds for the job market above all else. This also brings in themes about identity, marginalisation, oppression and race, class and gender.

Birth of a Nation (ITV, 19 June 1983), directed by Mike Newell, examines some of these questions and suggests a number of recurring themes and debates that then unfold throughout the other films. Essentially, Leland is concerned with how schools, the curriculum and teaching disenfranchise the child by simply processing their behaviour and abilities to make them suitable as components in a workforce.

However, he also shows how shortsighted this was at a time when there were few jobs available to a teenager, having done what teachers had encouraged them to do, thrust out into the real world of mass unemployment, union strikes and Thatcherite free market policies that were eroding the old traditions of a society and its relationship to the working class. He seems to be saying that we should not be surprised when pupils and teachers reject this state of affairs and demand changes in the way that knowledge and experience is transmitted from adult to child.

The film opens with one of Leland’s major themes, a brief sequence in the opening titles of children at play, instinctively learning by doing, defining themselves without recourse to institutional systems and their freedom of play placed in direct contrast to the demands of school, where children are contained and stratified according to their ability to pass exams. The sequence leads into hordes of pupils being addressed in an assembly by their headmaster Mr. Griff (Richard Butler) who immediately underlines the irony of the film’s title by telling his charges that “this school is like the nation. There are far too many people who are content to get away with seven out of ten. With more attention, with more concentration, with harder work these people could easily get eight out of ten or higher!”

The headmaster simply sees these children as a future workforce that will ensure the strength of the nation itself. As he does this, one of those who is “content to get away with seven out of ten”, Stephen Harris (Tony Seaborne) is adding graffiti to the toilet block and sitting down to enjoy a soft porn mag. Newell immediately contrasts the non-conformist individual with an overhead shot of the entire assembly where there is now a police sergeant, one of many symbols of the law appearing throughout the four films, addressing the pupils and conferring upon them the status of “citizens” subordinate to law and order.

It’s here that we are also introduced to the film’s central characters, recently appointed teacher Geoff Figg (Jim Broadbent) and veteran master Vic Griffiths (Robert Stephens) who will both epitomise the debate that Leland begins about the use of discipline in schools, where corporal punishment allegedly irons out the inconsistencies in recalcitrant pupils. After several more examples of pupils’ behaviour which also includes bullying and vandalism, the view point switches to Figg as he moves around the school and we see through him ‘traditional’ teaching methodologies contrasted with the open learning adopted by Tom Twentyman (a fabulous performance from Bruce Myers) and his Rural Studies class.

With Twentyman the pupils appear to be concentrating more whereas with the far stricter Mr. James other pupils are easily distracted by a gang of ex-students gathering at the school gates, whom he describes as a “most colourful collection” who “failed to acquire qualifications before setting foot in the real world” and informs his class that they now look back on lost opportunities. Figg’s class are also shown as a disruptive bunch, another “colourful collection”, seen as the lard of CSEs compared to the butter of O’ Level pupils being prepared by James, that the school has given to Figg and whom he eventually sees as deprived of the kind of open learning that Twentyman ascribes to.

Slowly we see Figg coming to understand that these children are subjected to punishments on a regular basis through an accepted, and rarely challenged, code of conditioning of behaviour. The drama therefore positions Figg and Twentyman as a liberalising agenda, one which understands that education should be about what the child wants to learn, naturally, rather than the traditional concept of what one of Figg’s pupils, Sylve, describes as: “copying out” and who demands of Figg “you’re the teacher, you’ve gotta take it out of your head and put it into mine. That’s your job.”

Thematically, Twentyman’s open classroom, where ‘play’ becomes a form of self-education, and Figg’s approach to frank group discussions about sex can be seen in bold contrast to Griffiths’s obsession with his overly complex and rigorously administered timetable and curriculum, Hodgeson’s devotion to that curriculum and Twentyman’s failure to grade his students’ work, and the headmaster’s middle class ignorance about what does happen to his ex-pupils beyond the school gate. It’s this binary of views that Leland explores and the consequences of Figg eventually shopping Griffiths and his punishment book to the local press. Hodgeson (Fred Pearson) also prefigures much of current education policy to constantly test all pupils, to determine their learning through rankings and league tables.

Elsewhere in the drama we see that little has changed, by the 1980s, about the gender norms that the pupils are contained within. A domestic science lesson therefore has a teacher demonstrating to girls how to make a Royal pudding, not by actually giving them the valuable experience of making the pudding and therefore perhaps learning from their mistakes in a practical fashion, but by simply getting them to write down the recipe as she, and only she, prepares the pudding.

Here, Leland makes a point about diminishing resources in education when a pupil questions this situation and the teacher retorts “this term you’re lucky you can watch me make things and I’m lucky to be here to make them.” There’s a rather unflattering shot of the female teacher, emphasising her rear, as she writes out the recipe and this is bookended and contrasted with the male pupils preparing for a PE lesson as the male PE teacher physically berates the fat kid of the class for being late.

The PE teacher cuts a rather strange figure and, although it is not implied in the film, there are instances where his interest in himself, sunbathing with an extremely small pair of briefs on and listening to the break-time gossip between Griffiths, Figg and Twentyman about some of the boys forming “wanking gangs”, raises questions about his own repressions. Again, this is reinforced later with a lingering shot of the PE teacher, naked from behind, that glorifies in his male physique as he stares at the centrespreads of pornographic magazines in his locker, symbols of female objectification perhaps he wanks over, yet all the while hypocritically humiliating one of the boys the others were talking about in the garden for doing much the same.

After the boys are put through an exercise regime and one of them is ritually humiliated, Leland cuts to the playground where one of the juniors is threatened with castration by Harris, the senior we saw vandalising the toilets at the start of the film. This perhaps suggests a learned behaviour, particularly from the PE teacher who physically punishes and mentally abuses his pupils. The older boys then repeat this pattern in their attitudes towards the younger ones. In a reverse of Harris’s menaces we later see Figg offering to reciprocate with Harris’s confiscated knife to “cut off your balls” when he catches him threatening a younger boy. It leads to a pivotal scene where Harris is forcibly held down by five adult men in Griffiths’ office to be beaten and where Figg is clearly revolted by the situation as much as the young boy waiting outside the office is utterly frightened by it.

Leland’s attitude is to demand what kind of learning can possibly go on in an environment based on fear and violence especially when Griffiths sees punishment as a result of the equation “treat them soft and they think you’re soft” and following the rules laid down in the oft-mentioned Staff Handbook. There seems to be a constant battle between male and female, between young and old where women are “lucky” to still be in the profession or are in secretarial roles and feared for the grim regimes they create in the school office and men are figures of narcissistic self-worship, become anal retentive patriarchs or are the ones who dole out the punishments.

When Hodgeson refers to unruly pupils “as thugs and prostitutes on a street corner” he is adding further layers to the classification of men and women, girls and boys in the film and tangentially underscoring the theme of sex education and gender roles within the story. The teaching about sex becomes an issue when Hodgeson discovers that Twentyman has been letting his pupils read informative and yet explicit text books about sex (‘Open Sex, Open Mind’ sums up quite emphatically a lot of the ideas about all education and not just that concerned with sex) and the headmaster reprimands him for circulating other literature about the subject.

Quite wonderfully Twentyman then demonstrates that the headmaster’s indignation is misplaced. After showing him a spanking magazine, one in which teacher/pupil scenarios are played out where, as Twentyman suggests, the headmaster could easily “divine the cause” of such sexual fetishes, he then reveals that ‘Open Sex, Open Mind’ is actually a book from the school’s library and the information is freely available to pupils and that pupils are now well aware that they are in a “spanking school” after Figg’s unwelcome publicity.

The theme of reproduction, probably best encapsulated in the birth of Twentyman’s child at the end of the film, is both the subject of that other institution, the NHS, and its own powerful management of his wife’s labour and connected to other ideas about the passing on of knowledge between generations, of securing the future through education. This is also supported by the proliferation of images of the natural world in Twentyman’s classroom and the school garden, where children are allowed to indulge in self-discovery in a miniature pastoral that is a direct contrast to the anonymous school and its urban surroundings.

After a former golden girl pupil, Alison, confronts the headmaster with her prospect of the dole even after “I did what you wanted. I did as I was told. I learned what I was told to learn. I reproduced it on paper. The way you wanted it” Leland revisits the spectre of well-educated youngsters, never taught to fend for themselves independently, now thrust out into an employment market devoid of jobs, the result of an education system geared towards a shallow reproduction all of its own. As the lost generation stalking the school gates eventually trash the school, Newell’s camera picks out Twentyman’s still intact room for Rural Studies amongst the wreckage, the calm at the centre of the hurricane, and the film ends with a succession of images of the room, taking in a caged magpie fluttering in distress, the school cat dining on a dissected rabbit, close ups of school photographs of Twentyman’s own youth, and current images of him happy with his own pupils.

Birth of a Nation is both blackly comic and acutely observed, perhaps overly biased towards Figg and Twentyman’s liberal responses, but it raised many questions on first transmission and quite a few of them are perhaps even more relevant today with an education policy wallowing in league tables and Cameron’s desire to to create a free market within state education. This desire is of course simply a continuation of Secretary of State for Education Keith Joseph’s free market ideas for the school curriculum, the training of teachers and dictating the role of the LEAs which he was in full pursuit of by the time he took on the job in 1981.

Leland’s themes move on to another stage in Flying into the Wind (ITV, 26 June 1983), the second film in the quartet and directed by Edward Bennett. Here, the emphasis is less about the school teacher’s job to educate the future workforce for a jobless market and is more firmly focused on how children can be educated outside of the system and the quality of instinctual learning away from a strictly controlled curriculum. The story concerns the parents of a young girl and boy and how they are prepared to go to court and argue that under the “… or otherwise” provisions of the Education Act of 1944 (which states “It shall be the duty of the parent of every child of compulsory school age to cause him to receive efficient full-time education suitable to his age, ability and aptitude, either by regular attendance at school or otherwise”) they should be allowed by law to home educate their children.

The film opens in 1969. A series of static shots establish the environs of a local school as the dominant, and physically containing, institution for education. We move into a classroom where a reading lesson is taking place. In the middle of the classroom is Laura Wyatt holding a book, ironically it’s Look and Learn and she is doing neither, seemingly anxious and distracted that she may be asked out in the front of the class to read aloud. Bennett cuts back to the austere establishing shot of the school, combining this with an equally anxious soundtrack of piano and sinister synths, as the diminutive figure of Laura leaves, to be followed moments later by a worried teacher. School as an educational institution is coded as threatening and unsympathetic.

Her parents Sally and Barry (Rynagh O’Grady and Derrick O’Connor) are summoned. Sally is pregnant with Michael, the other child who will figure centrally in the story, and Leland again emphasises the roles of parents, teachers, education officers and ultimately the police and the courts have in forming young lives from the moment they are born. There is a particular moment where Sally, distressed about her missing daughter, stands in the empty classroom looking at the rows and rows of empty desks, a vision that sees Leland’s recurring idea of how education impacts on a series of generations reintroduced. Barry’s factory foreman has a conversation, presumably informing him of Laura’s flight from school, that we are unable to hear due to the din of the factory floor, a temporary deafness that reflects the Wyatts’ discovery of their daughter’s own deafness, brought on after sleepless nights and instances of bedwetting and traumatic attempts to return her to school.

Early on we also see Leland’s suggestion that children learn of the world around them through direct experiences, through connections with events in their environment beyond the school gates, through simple acts of curiosity. This expands on the same theme established by Twentyman’s Rural Studies classroom where children explored and learned about the things they wanted to. A neighbour asks for Barry’s help with an elderly lady having difficulties getting out of the bath and we see Laura follow him and watch her father help the old woman. Laura is often seen acting out a desire to see beyond a series of doors that close in her face – here when the neighbour closes the bathroom door and later in a hospital when her mother goes into labour with Michael. As Dave Rolinson observes in his notes accompanying this release, “All four films associate doors with access and opportunity, or discipline and barriers.”

The scene in the neighbour’s bathroom touches on a recurring motif of generational support – just as Laura is depicted as a frail, anxious girl dependent on her parents then so is the elderly neighbour being helped out of the bath. Flying into the Wind‘s themes about interdependency run throughout the film, showing supportive, learning relationships between adults and children outside of the school environment. The nature of dependency is also reiterated in a slightly darker form in the two concluding films in the quartet. Later we see Barry and his son Michael (the brilliant Adrian Wagstaff) learning from each other as they construct a boat, witness Michael’s curiosity at the recovery of the dead body of a tramp from the marshes near where they live and, most importantly of all, the relationship between Michael and the Crown Court judge, Wood (an exceptional Graham Crowden).

The Wyatts eventually discover that their daughter has suffered temporary deafness as a result of her traumatic reaction to school and the Education Welfare Officer Harper warns Sally that she must send Laura to school as it is the law and a failure to do so will result in court summons and potentially the child being taken into care. Sally makes her position very clear that it is school that is causing the damage to her child and she will not force her to go. Much of the 1969 sequences are concerned with the power of institutions putting pressure on the Wyatts and Laura to comply with the law, to ensure they conform to the status quo of the education system and its structures.

… “we have not taught our children. We have enabled them to teach themselves…”

The film jumps to 1980 and the ultimate expression of this attempt to make them comply with the law is centred on the sequences in the Crown Court where Wood is first heard, in voice over, and then seen reciting the 1944 Education Act. The film is at its most didactic here, with Leland clearly reflecting his case research, but this is then punctuated with sequences that completely open the film out as it shifts from the urban, almost claustrophobic, background of the film’s opening to the Wyatts’ farmhouse and its location in the misty, marshy Lincolnshire landscape.

Here we are introduced to the 11 year old Michael, exploring this landscape and working on the boat in his father’s workshop. As his mother informs the judge that she believes her son will learn to read and write in his own time and all she can do is create the ideal conditions in which he will learn, Judge Wood suggests this problem still has not been resolved. Her view is that “we have not taught our children. We have enabled them to teach themselves” and Wood ultimately visits Michael to test that theory. We next see him as a tiny figure in the landscape, beautifully shot by Clive Tickner, as the representative of the law, of the Education Act itself, comes to observe Michael in his natural habitat, as it were.

Again, we have that idea of the proscribed education curriculum being supplanted by pastoral learning, knowledge acquired through experience, observation and the natural world. Wood treads along the same path that his alter-ego, the tramp, previously trod, both men of the world but of different learning and experience. The tramp represents Sally’s philosophy of survival in a tough world, one that she herself acknowledges is rapidly and violently changing. Ironically, it’s a struggle that the tramp ends with his accidental drowning in the very environment in which he was a rootless wanderer and the jetty where he drowns is also the same spot, a physical and metaphorical crossroad, where the film introduces Michael and later when Michael leaves for school.

The idea that children must learn by example and be allowed to make mistakes is writ large in the section devoted to Wood’s visit to the farmhouse, come to see for himself the environment that Michael learns in. The boat that he and his father builds is not watertight and when Michael takes Wood out they eventually sink and have to scramble ashore. Likewise, the van that he and Wood travel in gets stuck in the mud and they both have to walk back to the farmhouse. Wood also tests his knowledge of the local wildlife and particularly the heron, whose nest they disturb as they attempt to escape from the sinking boat.

He seeks to understand the extent of his knowledge and asks Michael about the number of species of heron and this becomes the symbol of the boy’s limits, one that the camera returns to at the end of the film where we see another series of school rooms, one which shows a picture of a heron on the wall just before Bennett’s camera swoops down to a sullen Michael in the middle of other school children in the school assembly, unable to join in the hymn because he is unable to read, at the limits of his experience. The children sing “All Creatures Great and Small” on the soundtrack, another link with the natural systems that Michael was nurtured within. Wood it seems has decided that just to simply ‘look and learn’ will not provide Michael with the ability to read and write. The structures of the institution have seemingly closed around him and like the boat full of holes, Sally’s arguments did not quite hold enough water to convince the court that Michael should continue to be home educated.

The film certainly raises questions about the efficacy and limits of a pastoral home education but also further establishes that there are other ways of educating children and that these can be tested in a court of law. The juxtaposition of various elements – the court and the structures of law in contrast with the open learning in a natural landscape, the generational difference between adults and children and the idea that sometimes these differences need to be reversed and the symbolism of birth and death – is more or less a development of those illustrated in Birth of a Nation. It’s a fascinating drama where Bennett’s directorial approach oscillates between the lyrical and the coldly formal.

Leland’s third film, RHINO (ITV, 3 July 1983), the acronym for Really Here In Name Only and attached to persistent child truancy, returns to a school environment similar to that of Birth of a Nation, its opening sequence underlining the effects of bullying and delinquent behaviour on other pupils and the teaching staff. But it is not just about the rights of the teacher, here upheld when Mr. Bartlett (James Warrior) persuades the headmaster of the school to suspend bully Tony, as the film is also more an exploration of how a teenager, Angie, simply fails to have a voice when she becomes enmeshed in the web of adults using their positions of power within the education system, social services and police and judiciary to direct the route that her life will take.

Angie (a standout performance from Deltha McLeod) firmly believes she already has a direction (“I have responsibilities”, she informs the school) and that it is to provide the domestic support to indolent brothers and an absent father as well as a parental duty to her brother’s abandoned child, Charley. In effect, Angie represents life beyond the school gates rather than within the school, reflecting the concerns that were raised in Birth of a Nation about the eventual fate of those who don’t achieve any qualifications at all. Her life is not centred on the classroom and, in discussing Jane Howell’s visual interpretation of this idea, Dave Rolinson eloquently summarises a number of shots in the opening of film placing her and other pupils “simultaneously inside and outside the school, suggesting institutionalisation (confining them within this building), and connecting school to the outside world.”

The theme of children “requiring bugger all” from the education system is reiterated as is the difference between the likes of Angie and Bartlett’s own “high-flyers” who will be pushed into succeeding at exams. In an echo of Laura’s refusal to attend school in Flying into the Wind, Angie’s friend Phil hates school so much that she throws up every morning she attends. In a discussion between Angie and Mr. Jellis (Derek Fuke), the Education Welfare Officer, we see the differences between Angie, having to face up to being a teenager on the verge of adulthood in a harsh, strictly controlled world, and Charley, under Angie’s charge, still a child learning through play and, much to Jellis’s annoyance, flooding the kitchen as he mucks about with buckets of water.

Jellis finds Angie’s lack of control over Charley an indication of her inability to look after the child whereas Angie just simply sees Charley engaged in harmless but developmental play that can be cleared up later. The idea of play as learning is contrasted with Jellis’s questioning of Angie’s desire to choose her favourite subjects at school. “Sometimes we have to be told what to do for our own good,” he states and reminds her that it is a tough world she is about to enter. He, like many of the adults in the film, underestimates her understanding of the world around her. She knows it’s tough and, like many teenagers finding themselves at odds with the education system, she criticises the way she is being educated, where “school don’t teach me nothing I need now.” School simply does not prepare young people adequately for the real world, Leland reminds us.

The most disturbing aspect of RHINO is that the authorities simply take her over, disabling her desire to run her own life, silencing her protestations as they pass her from court to care home and finally to secure unit. The spectre of institutional racism is raised too as all the figures of authority she comes into contact with and who discuss her case are white and in the main, male. The authority figure within her own family, her father, remains absent throughout the film until she finds herself in serious trouble for shoplifting and assaulting a policewoman, whom she claims called her a “nigger.” Leland frames this inequality within the case conference between Jellis, her social worker Joyce Barker and her teacher Bartlett, who believes Angie, seen as a “a large indolent lump in the middle of the classroom”, is going to become representative of the direct connection between race and crime. This is something which Barker refutes, even though Bartlett’s partially proved right when Angie assaults the policewoman and begins to reflect the negative stereotypes.

She finds Bartlett’s stereotyping problematic and his view that all West Indian children create these issues through poor self-image is to her incorrect. “They’re English” she protests, reminding us of the opening of the film using newsreels from 1949 of Princess Margaret addressing the pupils of a Berkhampstead school about acceptance of other boys and girls from the colonies. The newsreel provides an ironic counterpoint to the discussion as she is seen endorsing the The Royal Commission on Population’s view that immigrants of ‘good stock’ from the Commonwealth would be welcomed ‘without reserve’.

Leland is perhaps suggesting here that Angie is the victim of that legacy, the result of the muticulturalist project’s inability to facilitate basic human rights and equality, but he also further undercuts it by then immediately showing a skinhead gang chasing a young Indian boy through a town centre as a direct response to the Princess’s liberal PR exercise. So much for welcoming without reserve. It also pre-empts some of the complexities about racial stereotyping and its association with crime and delinquency in the final film, Made in Britain.

The axis of the film depends on the multitudinous voices of authority controlling Angie’s fate. The case conference sequence is a typical motif, of teachers and social workers talking about and deciding her course in her absence, often in voice over as we see Angie wandering the streets, sitting in a laundrette or a cafe. It culminates with her being caught shoplifting. All we hear are their voices, not hers, until she is bundled, screaming, into a police car. To this point in the film, Angie has been questioning of the system but feels no one is listening and that all the efforts of Jellis and the others make no difference. With the authorities deciding her fate after she is arrested for shoplifting and assault, she is placed in care but her overwhelming desire is to return home and to then brazenly pluck Charley from his care home, an action from which there is no turning back. Eventually, the forces of law and order do make a difference to her life but it is a decidedly negative one in the aftermath of the case conference which had praised Angie for coping with everything thrown at her after her mother’s death and with the absence of her father.

Another thing to note is that RHINO is primarily set within an urban milieu and that the previous links to the natural world as a freer environment in which to learn, are absent. This is a world devoid of the open learning of Tom Twentyman or the idyllic farmhouse of the Wyatts and the only reference to it is Charley’s innocent play in the kitchen or clutching his toy boat (a symbol that refers back to the home made boat in Flying into the Wind) and Angie sitting on a park bench looking out across the hill at the rest of the city. As she gets deeper and deeper into trouble, she becomes less and less articulate and disturbingly, by the end of the film, is reduced to a silent, anonymous young woman, picked over by the unsympathetic officers at the secure unit, literally stripped of her identity, her individuality and reduced to a state of incoherent vulnerability, just as Laura and Michael are subjugated in Flying into the Wind but here Angie is controlled without the additional focus of parental care. By the conclusion, a bright, articulate young woman is beaten into submission by the state and her only response is “it’s not right, y’know. It’s not right.”

The final film, Made in Britain (ITV, 10 July 1983), is certainly the most celebrated of the quartet. Here, Leland brings the themes explored in RHINO and the other films to a conclusion that proposes some teenagers are beyond the system and can only be controlled by detention centres and prisons. The main character, skinhead Trevor (Tim Roth) is not submissive, as Angie eventually is, to the vast array of power structures that descend upon him.

After his case is heard at the beginning of the film, his social worker Harry Parker (Eric Richard), driving him to an assessment centre, reels off a battery of activities that provide an allusion to Foucault’s analysis of a whole set of techniques and institutions for measuring and supervising abnormal citizens in Discipline and Punish. Mechanisms used by such individuals as “psychiatrists, psychologists, team leaders, key workers” will “decide what they think should be done with you,” notes Parker. If there is one conclusion you come away with from the film is that it is precisely this concentrated intervention in Trevor’s life that creates and sustains his transgressive attitudes towards authority. As Leland remarks, we “must look to our society” to understand how and why “Trevor is made in Britain” and the film shows Trevor as a self-centred young man who understands that he is his own creation, a progeny of the system’s failure to manage his delinquency.

One of the major differences is that the film is shot with Steadicam and visually it certainly produces a tension in simultaneously how close and how distant the audience can be with the ever restless Trevor. Director Alan Clarke had been reluctant to make Made in Britain and only when he saw cinematographer Chris Menges’s work using Steadicam on Stephen Frears’s Walter for Channel 4 did he feel that he could make something of Leland’s script and translate the central character’s explosive energy to the screen. The camera movement therefore becomes insistent, kinetic and representative of the pent up anger that Trevor channels throughout the film.

It also perfectly distills the walking contradiction of the character: he is intelligent and articulate but he’s also rebellious, self-centred, racist and violent. But he’s also the result of the system and as such is trapped in its spiral, eloquently illustrated when the Superintendent (the wonderful Geoffrey Hutchings) provides Trevor with a diagram, the endless loop of “no job, dole, thieving, prison.” It is one determined for him, one he actually accepts but often manipulates because he is as much distanced from what the system thinks is his life as he is from it.

When he bursts into the job centre in the first act of the film (his entry and exit through doors is always seen as an aggressive act), many of Leland’s previous observations in the earlier films are crystalised. A young lad, who clearly has not learned to read, has to ask Trevor to read the job ads for him, and we overhear a conversation between two girls about a dental reception job that apparently requires several O’ Levels and languages, where they conclude, “who d’you have to suck off to get that”. Ultimately Trevor takes that frustration with the criteria required by the job market and self-destructively uses it to vandalise the job centre after sardonically informing the clerk that he has umpteen qualifications and is “fluent in Urdu and Chapati.” It is a condemnation of the market and the impossible expectations foisted onto school leavers, whether you have qualifications or not, that Leland articulated in the character of Alison in Birth of a Nation. If that first film indicated a sense of origin for the contradictory nature of Trevor’s character then Made in Britain is perhaps an attempt to finally reveal the true face of Britain’s disenfranchised youth in the 1980s.

These explosions of anger culminate in the arrival of the Superintendent. After assaulting the kitchen staff at the centre, he’s thrown into an empty, dimly lit room. In a riveting twenty minute sequence, Trevor is first shown by the Superintendent his own history through diagrams on a blackboard and his probable destiny in the scheme of things – prison. Images of blackboards and their imparting of information are scattered throughout the films, auguring the strictures of the curriculum, open discussions about sex or in this case, a map of Trevor’s life. The word ‘wankers’ has also been seen on at least two of them, a salute from the other Trevors in the system.

After the Superintendent’s departure, Trevor articulates his position with uncompromising honesty to the two assessment centre officers, Peter (Bill Stewart) and Barry (Sean Chapman). He claims vehemently, “I’m British!” and that he’s proud of this heritage and despises Barry because he doesn’t share that sense of righteous patriotism, believing he doesn’t understand it because he’s spent “too much time locked up in here with these niggers.” He believes Barry “hates the blacks as much as I do only you don’t admit it.” Trevor believes he says many things people are actually thinking but are too afraid to voice in public.

Trevor equates this with a general fear of the ‘other’ in society. Anything the authorities don’t understand they lock away. In articulating his right wing anti-authoritarianism, he’s not exactly depicted as an anti-hero and is more a product of his times, his environment and the increasing intervention of the systems he’s been caught within, whereas he claims, he’s a “a star. I’m in exactly the right place at the right time.” In the sense that Trevor claims he’s British, perhaps as an aggressive ideologue he’s also a product of Thatcher’s legitimisation of selfishness in that infamous edict, there’s “no such thing as society.” He clearly sees the system has failed and argues “what are we going to do about you” when addressing Peter and Barry as representations of such a discredited structure.

We next see Trevor racing at a stock car rally. The stock car rally sequence features one final attempt by the system to channel and dampen his aggression but during the race, which he is clearly enjoying, Trevor’s car dies on him and his symbolic castration, dumped at the side of the track, simply fuels his anti-socialism further, almost as an admission that he doesn’t accept failure and to accept it is a sign of weakness. It precipitates a raid of the centre’s offices with Errol. Here, Trevor reads out Errol’s confidential file to him (like many of the youngsters in the films, Errol can barely read) and once again Trevor reiterates one of Made in Britain‘s controlling mantras – “your case conference coming up?” – that has been heard throughout the film, used as a bogeyman to keep inmates on the straight and narrow.

They steal a van and go on a spree of vandalism, attacking the homes of Pakistanis. This spree also raises the question of Trevor’s racism. He’s happy to cave the windows in of a Pakistani owned home and yet, for a period, befriends the young black man, Errol (Terry Richards), at the assessment centre. During the first act of the film Trevor actually mentors Errol, becoming the teacher who shows Errol an alternative to the a life of enforced education, even though it is all leading to purely criminal activity and a means to an end for Trevor before abandoning Errol and implicating him in the stealing of the van. It might be said that this briefly offers an insight into the tensions between different races in Britain, where Errol joins in with Trevor in verbally abusing the Pakistani residents, but it seems more like Errol is copying behaviour and Trevor’s racism is more opportunist rather than totally ingrained.

After Clarke’s Steadicam vision follows Trevor through a shopping area, where briefly he looks in the window of a shop at what seems like an idealised home life in a consumerist dream he is unable to have, and then to what one assumes is his former school, momentarily reflecting on his past it seems, he runs semi-naked (another image of the triumphant masculine body that echoes back to the PE teacher of Birth of a Nation) through the Blackwall Tunnel before owning up about his recent delinquency to Harry Parker. Having just seen the ideal home life in a shop window, here he is disrupting Harry Parker’s home, frightening his wife and children in one of the few spaces in the film that can offer any human warmth.

All this it seems is merely the prelude to “turning myself in” and his eventual fate in a police station cell. His world, a maze of blank corridors, doors, and of empty rooms into which cameraman Menges follows him, leads to the emptiest space of all, the police cell where his pathology, and Leland’s own project, is fully realised after the police officer informs him of the extent of his life from here on in. “There’s two things you’re going to learn. At home, at school, at work, in the street you will learn to respect authority and you will obey the rules. Just like everybody else. That’s discipline. Most kids know that by your age. Shut it. And keep it shut”

The final shot is a close up of Trevor with a fixed grin, part delight that he has fulfilled his tragic trajectory and is on his way to a detention centre or borstal but also part fear that he is now dealing with authorities who will counter his violence with their own. It’s also a direct challenge to him to become even tougher and that’s a theme the omitted ending to Made in Britain was promising to show.

About the transfers

Assuming from the quality that these were all shot all on 16mm, these four films now benefit from these high-definition transfers. Quality is greatly improved, as is detail, colour and contrast. They retain their natural grain and briefly catch some great detail but don’t expect reference quality because both the source material doesn’t provide it, where the use of fast film stocks and the film gauge are not inclined to offer it in the first place, and the dramas are themselves very much shot within the realist and documentary tradition. Still, they look great and are probably the best they’ve ever looked. Certainly Birth of a Nation and Made in Britain benefit the most with Flying into the Wind being perhaps the softer in detail of all the transfers seen here.

Special Features

Twice Told Tales (38mins, HD)

This short documentary opens with a group of teenagers attending a screening of Birth of a Nation upon which they comment at the end of the film. From there it moves to Leland providing background to the development of Tales Out of School beginning with Margaret Matheson’s appointment as Head of Drama at Central. Alan Clarke and Leland had pitched another idea to her and she instead wanted to do something about education. Thus Leland began his intensive research and started writing the four films. What strikes you is how television commissioning at the time was a much more trusting process between producer and writer and was done with little hand-wringing. Leland even confesses his research took in his masquerading as a window cleaner and going into a school to clean the windows. He offers that he never provided any conclusions or suggestions as to what the solutions to the problems shown the films would be and provides background to his exploration of the 1944 Education Act and what happens when a child falls out of the system. This is a great little documentary that explores in good detail the themes in the films and how each film was developed and directed.

Digging for Britain (29mins, HD)

This second documentary focuses on the making of Made in Britain and Leland’s relationship with director Alan Clarke. Again we get interviews with Leland and Matheson as well as Stephen Frears who explains how excited Clarke was about the use of Steadicam. Clearly it opened the film out and developed it from Leland’s view of it as a locked down, static production. Leland also mentions the problem he faced with using language in the film and that he spent time with a social worker and local skinheads to develop the character of Trevor. He discusses the skinhead iconography and racist attitudes which eventually made their way into the film. There are some very fond memories of Clarke himself, rehearsing Tim Roth and the others, from actors Sean Chapman and Eric Richard and of the iconic sequence featuring Geoffrey Hutchings. There is also a fascinating glimpse of Made in Britain‘s original final scene, omitted from the finished version, where Trevor is seen digging trenches at borstal and the scripted scene is presented with a series of production stills at the end of the documentary.

Image Gallery (HD)

A good selection of images from each of the films and including a number from the omitted final scene of Made in Britain.

Booklet

Dave Rolinson provides an exceptionally detailed exploration of the films in this 36 page booklet, including an examination of their themes and production and the impact they had both in the media and at screenings in schools with an abundance of references from contemporary reviews.

Tales Out of School

Birth of a Nation /Flying into the Wind / RHINO / Made in Britain

Central Independent Television 1983

Network DVD / Released 4 July 2011 / 7957040 / 2 – disc Blu Ray / 300 mins approx / Region: B – PAL / Subtitles: None / Sound: Mono – English / Picture: 1.33:1 – Colour / Cert: 18

Network site entry for the blu-ray release.

Originally posted: 10 July 2011.

[This piece first appeared on the Cathode Ray Tube website on 10 July 2011.]

Pingback: ‘An ideology red, white and blue in tooth and claw’: David Edgar’s Destiny (1978) – Part 3 of 3