by TOM MAY

Play for Today Writer: David Edgar; Producer: Margaret Matheson; Director: Mike Newell

This essay continues from Part 2.

Part 3: Analysis of Destiny and its afterlife

Please note that, in order to explore this programme and its political context, this essay quotes racially offensive language.

Visual motifs, setting, culture and class

In its adaptation to television, the play’s text was sometimes faithfully translated, but Edgar made significant alterations and changes of emphasis. The medium is used to historicise the play with exact dates – “15th August 1947”, “20th April 1968”, “19th June 1970” and “1977” – being presented. The stage version’s text does not as clearly indicate the year of the contemporary scenes.

In its adaptation to television, the play’s text was sometimes faithfully translated, but Edgar made significant alterations and changes of emphasis. The medium is used to historicise the play with exact dates – “15th August 1947”, “20th April 1968”, “19th June 1970” and “1977” – being presented. The stage version’s text does not as clearly indicate the year of the contemporary scenes.

As on stage, the painting showing the putting down of the Indian Mutiny is a key visual motif.1 This is shown three times throughout the play: in the opening India scene, in the Northern Ireland army HQ, and in the hospitality room of the City of London merchant bank in the final scene. A gramophone is added to the India set, alongside the stuffed tiger referred to in the text. There’s much connotative period detail, but less specificity: the play text states its setting as Jullundur in the Punjab. On television, it is merely “India”.

As on stage, the painting showing the putting down of the Indian Mutiny is a key visual motif.1 This is shown three times throughout the play: in the opening India scene, in the Northern Ireland army HQ, and in the hospitality room of the City of London merchant bank in the final scene. A gramophone is added to the India set, alongside the stuffed tiger referred to in the text. There’s much connotative period detail, but less specificity: the play text states its setting as Jullundur in the Punjab. On television, it is merely “India”.

Posters and banners are made prominent. In Turner’s antique shop in 1970, we see a poster with the soon-to-be ironic message: “VOTE CONSERVATIVE FOR A BETTER TOMORROW”, and a poster of Edward Heath looms over the seated Turner from its position attached to the shop window. This scene also presents the garishly dressed Goodman, who has a carrier bag with the Union flag emblazoned on it. This appropriation of the national symbol signifies the sort of commodification of identity loathed by Turner and Rolfe, and represents Goodman as Turner’s enemy, embodying rootless, speculative capital. In the Labour Club scenes, a poster reads “With your help, Labour will go from strength to strength”, and a later picket-line scene includes a poster bearing the slogan “Britain can win with Labour”. The Nation Forward public meeting opens with the prominent display of the capitalised “TADDLEY PATRIOTIC LEAGUE” banner, which emphasises the movement’s nativist attachment to local identity.

Posters and banners are made prominent. In Turner’s antique shop in 1970, we see a poster with the soon-to-be ironic message: “VOTE CONSERVATIVE FOR A BETTER TOMORROW”, and a poster of Edward Heath looms over the seated Turner from its position attached to the shop window. This scene also presents the garishly dressed Goodman, who has a carrier bag with the Union flag emblazoned on it. This appropriation of the national symbol signifies the sort of commodification of identity loathed by Turner and Rolfe, and represents Goodman as Turner’s enemy, embodying rootless, speculative capital. In the Labour Club scenes, a poster reads “With your help, Labour will go from strength to strength”, and a later picket-line scene includes a poster bearing the slogan “Britain can win with Labour”. The Nation Forward public meeting opens with the prominent display of the capitalised “TADDLEY PATRIOTIC LEAGUE” banner, which emphasises the movement’s nativist attachment to local identity.

In 1987, Edgar, reviewing Paul Gilroy’s book, There Ain’t No Black in the Union Jack, argued in favour of a left-wing localism over nationalism:

the future of the radical project will be located not in generalised and ideologically dubious evocations of a vaguely popular-fronted Churchilliana, but in the struggles of specific and often local communities whose rootedness in tradition and immediate social relations is the essential basis of a radical response to social change.2

The Labour Club in Destiny is a positive exemplar of this kind of social environment, a setting that nurtures radical actions such as solidarity with the striking Asian workers. In contrast, the NF headquarters is presented as a nativist dead end, peopled by the uninitiated. In the original text, Tony and Liz make a banner with “A union jack, behind an applique white family”, which bears the archetypal fascist slogan “The future belongs to us”, which elicits Cleaver’s approval.3 This is removed, suggesting lack of agency on these minor characters’ part, with Cuthbertson’s domineering Cleaver having less meaningful interaction with them.

Settings are critical to the play. The text’s Act 2 Scene 3, where Clifton meets with the striking Asian workers, is moved from the Labour Club to the picket-line outdoors. This is represented on television via a bare and dark studio set, presumably the result of budgetary disciplines. We see a brick wall, lamps, a staircase and a few posters. The scene is distilled, with some of the more direct dialogue from the original cut, such as Patel’s “And with a racist party, in the bye-election. Making propaganda. Leafletting. And so on.” Later, the entire Act 3 Scene 2 of the play is excised, losing dialogue between the Asian strikers, Platt, Attwood and a policeman. In addition, Patel’s aggression towards Attwood, pushing him and branding him “You bastard blackleg scab” is cut, softening Patel significantly. The picket-line setting on television lacks the veracity that a more drama-documentary aesthetic would have created; there is a paucity of extras, and the sound effect of a distant-sounding crowd.

Settings are critical to the play. The text’s Act 2 Scene 3, where Clifton meets with the striking Asian workers, is moved from the Labour Club to the picket-line outdoors. This is represented on television via a bare and dark studio set, presumably the result of budgetary disciplines. We see a brick wall, lamps, a staircase and a few posters. The scene is distilled, with some of the more direct dialogue from the original cut, such as Patel’s “And with a racist party, in the bye-election. Making propaganda. Leafletting. And so on.” Later, the entire Act 3 Scene 2 of the play is excised, losing dialogue between the Asian strikers, Platt, Attwood and a policeman. In addition, Patel’s aggression towards Attwood, pushing him and branding him “You bastard blackleg scab” is cut, softening Patel significantly. The picket-line setting on television lacks the veracity that a more drama-documentary aesthetic would have created; there is a paucity of extras, and the sound effect of a distant-sounding crowd.

This minimalist setting is also used for Crosby’s meeting with Clifton where they discuss a “common front” against the fascists; in the original text, this had been in Clifton’s home, but is made more public here. The sad, nostalgic speech Crosby had spoken to Platt on stage is here shared with his Labour opponent Clifton: “I remember long ago when I was a small boy […] a homely, dainty patriotism”. He is given additional dialogue describing the NF’s “grisly xenophobia”. This is another move that softens and humanises Crosby, who is presented as fundamentally different from the NF and Rolfe and someone who represents the moderate tradition of engaging with political opponents. The scene has ideologically charged symbolism: a Tory visiting a picket-line for friendly dialogue; though the impact is lessened by the picket line being so empty. Its void-like aesthetic is in the mould of Gerald Savory’s unadorned staging for the maligned Churchill’s People (1974-75). Savory described his methodology thus: “A mast, a sail, a few upturned boxes, the sound of the sea and wind is a ship.”4

This minimalist setting is also used for Crosby’s meeting with Clifton where they discuss a “common front” against the fascists; in the original text, this had been in Clifton’s home, but is made more public here. The sad, nostalgic speech Crosby had spoken to Platt on stage is here shared with his Labour opponent Clifton: “I remember long ago when I was a small boy […] a homely, dainty patriotism”. He is given additional dialogue describing the NF’s “grisly xenophobia”. This is another move that softens and humanises Crosby, who is presented as fundamentally different from the NF and Rolfe and someone who represents the moderate tradition of engaging with political opponents. The scene has ideologically charged symbolism: a Tory visiting a picket-line for friendly dialogue; though the impact is lessened by the picket line being so empty. Its void-like aesthetic is in the mould of Gerald Savory’s unadorned staging for the maligned Churchill’s People (1974-75). Savory described his methodology thus: “A mast, a sail, a few upturned boxes, the sound of the sea and wind is a ship.”4

The picket-line scene is especially minimalist when compared with Leeds United!, a Play for Today in which director Roy Battersby employed extras as vast crowds of strikers and, as Dennis Potter observed in his review, used “long, steady pans and elaborate tracks” that subtly conveyed “deep emotional commitment”.5 In contrast, Newell does not intend Destiny to be a drama-documentary; its aesthetic is somewhere between the studio-based, anti-naturalist minimalism of Churchill’s People and what Ian Greaves and John Williams describe as the “realist aesthetic” of the entirely-location filmed Days of Hope.6 Newell’s predominantly studio aesthetic usually tends to reflect naturalism, though the picket-line scene stands out as minimalist. The scene’s complexity is heightened by Crosby’s lack of complacency, as he speaks to Clifton about the NF being “our creation” and resulting from the post-WW2 era. Critic Day-Lewis commented that Edgar had managed to show how “reasonable discontents” with the present had influenced the rise in fascist support, as well as “unreasoning fear of immigrant infiltration.”7

Rolfe’s introductory poem is read over a scene of him in business-wear sitting on a train carriage in the midst of modern Britain. In contrast, the theatre version depicted him in an empty set, standing in the centre, in a black overcoat and “with medals and a poppy”. Newell and cinematographer Crosby isolate Rolfe, who is alone on the carriage and given twitchy and despondent expressions by Hawthorne. Towards the end of this sequence, Rolfe spots an Asian and a black man walking past on the train, and gives them a frowning look: connoting that ethnic diversity is part of Rolfe’s doomy, declinist vision of Britain. During Colonel Chandler’s funeral, like the train sequence shot on film, and a rare use of outdoor location, Hawthorne emphasises Major Rolfe’s bitter anger with his shouted delivery: “Will it be any different next time!?” He is also given the hyperbolic abstract noun “Armageddon” when outlining his vision of the left-wing threat to Britain, which he sees as embodying unreasonable discontent.

One of the most compelling scenes is of Rolfe mourning his son’s death in Northern Ireland; its setting in Lisburn, Northern Ireland is implied through the addition of a soldier on the door as Rolfe enters. As in the original text, there is a coffin with a Union flag draped over it. The scene is made more naturalistic than on stage with Rolfe’s “You still won’t see? […] Will you?” losing its direct address; the change to third-person pronouns makes it more detached and private: “And they still won’t see, will they?” Dennis Potter’s glowing review focused especially on this scene:

One of the most compelling scenes is of Rolfe mourning his son’s death in Northern Ireland; its setting in Lisburn, Northern Ireland is implied through the addition of a soldier on the door as Rolfe enters. As in the original text, there is a coffin with a Union flag draped over it. The scene is made more naturalistic than on stage with Rolfe’s “You still won’t see? […] Will you?” losing its direct address; the change to third-person pronouns makes it more detached and private: “And they still won’t see, will they?” Dennis Potter’s glowing review focused especially on this scene:

The sight of Nigel Hawthorne weeping as he plucked at the folds of a Union Jack managed to be both disgusting and moving, thrilling and dangerous, an absolution and an accusation, at one and the same time. Great acting, great writing, great direction; among the very best I have ever seen. Malignancy charted.8

Hawthorne conveys how Major Rolfe’s personal despair and grief and are intermingled with politics and history, with a performance of physical stillness and quivering vocal passion. Hawthorne convincingly conveys the dark paradox of Edgar’s dialogue and how Rolfe feels more sympathy for the “12-year-old boy killer in the Divis flats” than the British generals and the ministers. The end of the scene is significantly altered; unlike on stage, Kershaw is present, as is gradually revealed.

The closing line of this scene (and of Act 2) of the stage version is omitted from the television version: Rolfe’s authoritarian statement “We need an iron dawn” and Rolfe holding up the Union flag. Instead, the Tory Kershaw is given rueful but defiant dialogue that Rolfe alone had spoken in the stage version. Its inclusion following Rolfe’s monologue directly links their shared desire for a right-wing counter-attack with the strike situation at Baron Castings: “They say they’ll get them in. Unthinkable, to use these people… Impossible not to, all other options closed”. This refers to their making use of the NF to break the picket-lines; this may be Edgar alluding to the situation at Grunwick in the summer of 1977 where the right-wing NAFF assisted George Ward, the photo processing plant’s boss. The last section of Kershaw’s dialogue is heard over the opening of the next scene: a tableau of the flag-wielding NF, applauding the abashed Turner, wearing an election rosette, all ready to set off for the picket-line. This scene is entirely new for the television version, showing Cleaver arriving to much heartier applause than Turner, followed by his imperative to his troops: “Right, let’s go!”

Following this, there is a significant and rare dialogue-less scene, using slow-motion. A striker’s placard bearing the slogan “DON’T SCAB, THIS IS YOUR FIGHT” is framed in opposition to a union jack. As we hear a police siren, we see Paul being led to a cell by the police. This scene creates a greater immediacy. However, the television version often reduces specificity and topicality: for example, removing Platt’s imperative alluding to the Birmingham automative plant, “Concentrate on hards from Longbridge”.9 Crosby’s “Roll on the North Sea Oil, say I” is likewise excised. However, Edgar does keep the oblique reference to David Stirling’s GB75 organisation, as Rolfe and Kershaw discuss “private armies”. This scene is subtler on television, with Kershaw’s aghast “Not in England…” replacing the blunter stage dialogue: “You’re seriously suggesting – army into Government? […] In England?”10 Kershaw’s affirmative quotation of R.A. Butler in this scene is deleted, making him less obviously a “One Nation” Conservative, a mantle Crosby claims in the television version. Rolfe’s dystopian vision is given greater detail with new dialogue: “Starts with unofficial strikes in Yorkshire […] OPEC countries raise the price of oil”. This locates Rolfe’s paranoia regionally and within 1970s geopolitics.

Following this, there is a significant and rare dialogue-less scene, using slow-motion. A striker’s placard bearing the slogan “DON’T SCAB, THIS IS YOUR FIGHT” is framed in opposition to a union jack. As we hear a police siren, we see Paul being led to a cell by the police. This scene creates a greater immediacy. However, the television version often reduces specificity and topicality: for example, removing Platt’s imperative alluding to the Birmingham automative plant, “Concentrate on hards from Longbridge”.9 Crosby’s “Roll on the North Sea Oil, say I” is likewise excised. However, Edgar does keep the oblique reference to David Stirling’s GB75 organisation, as Rolfe and Kershaw discuss “private armies”. This scene is subtler on television, with Kershaw’s aghast “Not in England…” replacing the blunter stage dialogue: “You’re seriously suggesting – army into Government? […] In England?”10 Kershaw’s affirmative quotation of R.A. Butler in this scene is deleted, making him less obviously a “One Nation” Conservative, a mantle Crosby claims in the television version. Rolfe’s dystopian vision is given greater detail with new dialogue: “Starts with unofficial strikes in Yorkshire […] OPEC countries raise the price of oil”. This locates Rolfe’s paranoia regionally and within 1970s geopolitics.

Edgar updates his text for its location in 1977 – a year that was in the future when he wrote the theatre play. To follow Platt’s “Send in the gunboats”, the line “show the IMF who’s boss!” topically refers to the IMF loan “crisis” of late 1976, replacing the theatre version’s “Sort the Saudies out that way”, which alluded to the Oil Crisis.11 In the NF public meeting scene, Edgar cuts Mrs Howard’s negative references to the Common Market and her mourning the loss of Samuel Smiles-inspired values of “self-help and discipline”, keeping the focus forensically on her regret at the loss of Empire.12 Maxwell’s dialogue in the same scene about capitalists compromising with the Communist East via détente is also cut; perhaps this seemed less germane in late 1977 than a year earlier. This scene also has Liz presciently referring to “home ownership” as a core Tory promise being betrayed and Mrs Howard speaks on behalf of the “silent majority” who, in reality, were won over by Thatcher’s politics, not the NF’s. It is easy to imagine Liz later becoming a working-class Tory voter, following the selling-off of council houses. Notably, the television version omits Bob Clifton’s intertextual reference in the play to the BBC’s most famous fictitious bigot: “Like when I’m on the doorstep, confronting the massed Alf Garnetts of the West Midlands.”13 This lessens the sense of the Labour candidate clashing with a section of the working-class electorate who are said to use words like “darkies” and who Johnny Speight satirised through Alf Garnett.14

Edgar updates his text for its location in 1977 – a year that was in the future when he wrote the theatre play. To follow Platt’s “Send in the gunboats”, the line “show the IMF who’s boss!” topically refers to the IMF loan “crisis” of late 1976, replacing the theatre version’s “Sort the Saudies out that way”, which alluded to the Oil Crisis.11 In the NF public meeting scene, Edgar cuts Mrs Howard’s negative references to the Common Market and her mourning the loss of Samuel Smiles-inspired values of “self-help and discipline”, keeping the focus forensically on her regret at the loss of Empire.12 Maxwell’s dialogue in the same scene about capitalists compromising with the Communist East via détente is also cut; perhaps this seemed less germane in late 1977 than a year earlier. This scene also has Liz presciently referring to “home ownership” as a core Tory promise being betrayed and Mrs Howard speaks on behalf of the “silent majority” who, in reality, were won over by Thatcher’s politics, not the NF’s. It is easy to imagine Liz later becoming a working-class Tory voter, following the selling-off of council houses. Notably, the television version omits Bob Clifton’s intertextual reference in the play to the BBC’s most famous fictitious bigot: “Like when I’m on the doorstep, confronting the massed Alf Garnetts of the West Midlands.”13 This lessens the sense of the Labour candidate clashing with a section of the working-class electorate who are said to use words like “darkies” and who Johnny Speight satirised through Alf Garnett.14

In the scene in Turner’s shop, the television version cuts down detailed explanatory dialogue about the 1970 General Election, instead conveying it economically through the use of a Daily Express front page. However, Goodman does say “I’m a Selsdon Man, like ’im!”, pointing to the image of Edward Heath. The Colonel’s poem begins while we see Turner taking down and folding up his Conservative election poster. This makes more explicit the link between Turner and the dying Tory MP Colonel Chandler, and emphasises Turner’s sense of grievance and betrayal by his “own” Party, which he sees as being invaded by spiv capitalists like Goodman. Turner’s status as shopkeeper is emblematic: Margaret Thatcher’s greatest inspiration was her father, Alfred Roberts, not just a Conservative councillor in Grantham but, importantly, a grocer.

Although cultural allusions are significant, the television version gives a reduced role to music. We hear The Last Post at Colonel Chandler’s funeral but the programme does not retain the text’s use of an unspecified piece by Handel as the stage blackouts at the end of Act 1 or the use of “A German recording of the SS marching song’ Horst-Wessel-Lied at the end of the scene set in 1968.15 More significantly, Edgar chose to remove Tony Perrins’ guitar and vocals musical setting of Rudyard Kipling’s poem The Beginnings,16, which Turner describes as “a patriotic song”.17 This was originally used towards the end of the Taddley Patriotic League meeting. This five-stanza poem, with its refrain “the English began to hate”, was arguably dramatically superfluous following the audience contributions and Maxwell’s speech, added to which it is unlikely that a disaffected working-class youth would know and sing Kipling in 1977: as Orwell argued, in Kipling’s day, the masses were “bored” by the Empire and his audience was primarily “the ‘service’ middle class, the people who read Blackwood’s’.18 Orwell also mentioned how erroneous much left-wing criticism of Kipling as a “fascist” could be, arguing that he was a “Conservative [who] identified with the ruling power and not with the opposition.”19

While this omission may have been a wise move, creating greater naturalism, it means the television play has less connection with a source of mythical Englishness. Rob Young and Peter Ackroyd, in different books about national identity and music, feature extensive discussion of Kipling’s strange collection of stories, Puck of Pook’s Hill (1906), where ash, oak and thorn leaves give the children access to earlier times. In his biography of Kipling, published the year the television Destiny was recorded, Angus Wilson discusses how the collection embodies some of Kipling’s most cherished themes; he mentions how ‘The Knife and the Naked Chalk’ expresses the archetypal libertarian right-wing myth of “the terrible price to be paid by the individual for society’s advances”.20 It is easy to imagine the child Peter Crosby as an avid young viewer of the 1951 television adaptation of Puck of Pook’s Hill.21 Kipling’s ideas do circulate in the television play.22 Edgar keeps the illusion to the “White Man’s Burden”, a famous phrase attributed to Kipling, in the opening scene in India.

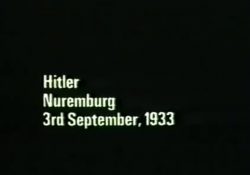

The music used at the end, following the Hitler quotation’s delivery in RP-accented voice-over, is a recording of the sombre ‘March’ from Henry Purcell’s Music for the Funeral of Queen Mary, first performed at Queen Mary II’s funeral in March 1695. Purcell is perhaps best known for his opera Dido and Aeneas (1689) and the song ‘Nymphs and Shepherds’ (1695), famously recorded in 1929 by the Manchester Children’s Choir with the Hallé Orchestra. Purcell’s music has been used in an eclectic range of films: Powell and Pressburger’s A Canterbury Tale (1944), A Clockwork Orange (1972), Kramer Vs. Kramer (1979) and Trevor Griffiths and Ken Loach’s Fatherland (1986).23 Purcell’s music, described by Peter Ackroyd as having a “plangent sadness”, is used by Newell to connote a funereal mood at the play’s conclusion, with national decency in jeopardy as malevolent forces unite.24 The Hitler reading maintains the sense of historicity, with the text appearing on the screen, in white font on a blank black background, accompanied by its exact date.

The music used at the end, following the Hitler quotation’s delivery in RP-accented voice-over, is a recording of the sombre ‘March’ from Henry Purcell’s Music for the Funeral of Queen Mary, first performed at Queen Mary II’s funeral in March 1695. Purcell is perhaps best known for his opera Dido and Aeneas (1689) and the song ‘Nymphs and Shepherds’ (1695), famously recorded in 1929 by the Manchester Children’s Choir with the Hallé Orchestra. Purcell’s music has been used in an eclectic range of films: Powell and Pressburger’s A Canterbury Tale (1944), A Clockwork Orange (1972), Kramer Vs. Kramer (1979) and Trevor Griffiths and Ken Loach’s Fatherland (1986).23 Purcell’s music, described by Peter Ackroyd as having a “plangent sadness”, is used by Newell to connote a funereal mood at the play’s conclusion, with national decency in jeopardy as malevolent forces unite.24 The Hitler reading maintains the sense of historicity, with the text appearing on the screen, in white font on a blank black background, accompanied by its exact date.

Although the television version keeps the allusion to Kipling, it removes all textual references to Winston Churchill and Lord Mountbatten.25 It also removes Kershaw’s scornful reference to “Mr Wedgwood Benn” and the theatre version’s topical references to “moderate” Labour figures such as Reg Prentice and Roy Jenkins, which had clearly defined Paul as an oppositional leftist insurgent. This is evidence of Edgar trying to aim at a less specialist television audience. However, he does also change Rolfe’s dialogue about the Tories “Genuflecting to the fashionable myths” to them “still genuflecting to the sacred cows of Congress House”. This greater emphasises the Major’s hatred of trade union power; Congress House being the TUC’s Headquarters since its opening in 1958.26

Social class is important throughout. Within the India scene, army rank and hierarchy are emphasised, as is Rolfe’s more lowly educational background: the fact that he didn’t go to prep-school, unlike his commanding officer Colonel Chandler. Rolfe thus lies closer to Turner in class than the Tory grandee Chandler and refers to himself as being from “the lower middle-class”. Turner’s petit-bourgeois class is disclosed in his reference to “old virtues, thrift and prudence, despised” and details such as the front page of the Daily Express being visible on his desk in the 1970 sequence, its headline signifying historicity: “Marginals are falling to Heath – TORIES RACE TO VICTORY”. Edgar further emphasises Maxwell’s sense of social superiority to the plebeian Turner in this new dialogue for the television version: “I have had all morning with Turner and his medical paranoias”. Maxwell sees Turner’s base conspiracy theories as beneath his socialism-infused vision; Maxwell was identified by Day-Lewis as a paradoxical “racialist-Trotskyite”.27 When he finally abandons the NF, due to his preference for “the masses” and distrust of Cleaver’s messianic leadership style, Blatchley plays him as more clearly scoffing than the original text suggested. Cleaver ultimately enforces his traditional views of class on the party when arguing with the “bolshie” Maxwell: “some were born to lead, others were born to follow”.

The depth of Edgar’s portrayal of the varying far-right characters reflects his support – expressed later, in 2005 – for the BBC’s public service remit to “give a voice to those who aren’t heard”.28 Similarly to the right-wing characters’ discourses in Peter Nichols’s The Common, the Tory Platt refers it now being “very dodgy” with the “new estates” [council estates]. In his 1968 speech, Cleaver uses sexist humour, which indicates Edgar’s greater gender critique in the television version: “a good speech should be like a woman’s skirt: short enough to arouse interest but long enough to cover the subject!”

Representations of ideologies

The sparsely populated room – and scattered seating pattern – connotes atomised individuals in contrast to the affable, cordial characters associated with Labour. This scene tellingly portrays the far-right’s organisational amateurism, yet also portrays how skilfully Maxwell draws out chilling, but humanly plausible, resentments from those gathered. Through Attwood, Edgar dramatises the social conservatism of working-class Labour voters, as more broadly depicted in a mainstream sitcom like Love Thy Neighbour (Thames, 1972-76). His resentment at immigration is subtly conveyed; Stacy Davies plays the part with negative body language, his folded arms conveying his telling class-based contempt for Mrs Howard. Edgar slightly softens this character for the television version by omitting his dialogue: “I’ll be quite frank about the blacks” – another signifier of a more implicit approach. This approach is seen later when Maxwell’s original dialogue “Richard, we can reprint Mein Kampf if it’ll make you –” is changed for television to: “Some, I suppose [are born to lead]. Meaning you…”

The sparsely populated room – and scattered seating pattern – connotes atomised individuals in contrast to the affable, cordial characters associated with Labour. This scene tellingly portrays the far-right’s organisational amateurism, yet also portrays how skilfully Maxwell draws out chilling, but humanly plausible, resentments from those gathered. Through Attwood, Edgar dramatises the social conservatism of working-class Labour voters, as more broadly depicted in a mainstream sitcom like Love Thy Neighbour (Thames, 1972-76). His resentment at immigration is subtly conveyed; Stacy Davies plays the part with negative body language, his folded arms conveying his telling class-based contempt for Mrs Howard. Edgar slightly softens this character for the television version by omitting his dialogue: “I’ll be quite frank about the blacks” – another signifier of a more implicit approach. This approach is seen later when Maxwell’s original dialogue “Richard, we can reprint Mein Kampf if it’ll make you –” is changed for television to: “Some, I suppose [are born to lead]. Meaning you…”

In the 2017 French film Chez Nous (This is Our Land), Émilie Duquenne plays a disaffected nurse who turns to the far-right and becomes a Marine Le Pen-style electoral figurehead. Liz might have been a comparable character, but her role is reduced in comparison with the play; unlike Tony, who retains his importance through his prison “reunion” scene with Paul. Liz’s longest bit of dialogue is cut to just: “I want a reason to have children”. This removes her story of disillusionment leading to her giving up sewing and her declinist arguments: “Our country’s rotting. Fabric’s perished. Ripping at the seams.” It also loses her articulation of finding a home and a sense of identity in the Taddley Patriotic League. Instead, Sandy’s speech about working-class voters stands for much of her resentment. Her sense of grievance felt is due to powerlessness, with centralised government seen as high-handedly ignoring local opinion and imposing its will: a feeling Rudyard Kipling would have empathised with, never being as at home with British culture following the growth of the Whitehall apparatus due to geopolitical developments and the invention of the telegraph after 1914.29

In the meeting scene, Maxwell’s skilful communication includes his allusive: “to use a light-hearted phrase, we all feel ‘Fings ain’t what they used to be’”. As well as synthesising the disparate grievances around the room, he taps into his audience’s nostalgia and its shared memories of popular musical theatre; indeed, as noted earlier, the programme was broadcast on BBC1 shortly after The Good Old Days, which offered a nostalgic version of Victorian popular entertainment. It is unlikely those gathered in the Taddley Patriotic League would have known that Lionel Bart’s light-hearted musical, Fings Ain’t Wot They Used T’Be, was first produced by Joan Littlewood’s left-wing Theatre Workshop.30 Maxwell may have known, though. He has a good deal of the socialist about him, bringing him into conflict with Cleaver. Maxwell’s smooth way with words, brilliantly captured by Joseph Blatchley, is contrasted by the dour, gauche Turner.31 Unlike in the theatre text, Maxwell delivers a short, near Hitler-style salute near the end of his speech, signifying Edgar’s view of the NF as ultimately a Nazi front. Maxwell’s complexity is shown by Edgar giving him the angry words “We are not ex-Tories with a thing about the wogs”, dialogue in the television version which replaces the theatre version’s “We are not ersatz Conservatives with a particular distaste for immigration.” Edgar also removes the pre-modifiers he originally gave to Maxwell’s noun phrase: “backwoods Conservative elitism”. This blunter, more colloquial dialogue adds to the portrayal of the public-schooled Maxwell as a clever populist. While Turner is portrayed with empathy and his motivation is convincingly established, his unreconstructed racism is not soft-pedalled: the television version keeps his line to Crosby (“Oh, after the nig-vote, are we?”),32 and gives him the additional line that makes him sound like a West Midlands Bernard Manning: “And have you heard the one about the Paki?”

Cleaver’s speech, on the day of Powell’s “Rivers of Blood” speech, is foregrounded in the television version, moved from being Act 1 Scene 6 to Scene 2: directly after the Indian independence day. Edgar creates a greater subtlety in this scene by omitting the characters’ toast to “The Fuhrer”, though the picture of Hitler and Union flags are prominently displayed as part of the mise en scène. The scene in which Cleaver and Maxwell school Turner as a candidate via cross-examination shows their far-right campaign’s central focus on how non-whites “take jobs that would normally be given to the whites”. This scene becomes gradually more chilling, as the manipulative Cleaver leads Turner towards Anti-Semitism, naming communists and big business people united by race: “Rothschild. Marx. Kissinger. Rosa Luxemburg. Oppenheimer. Lev Davidovitch Trotsky. What they have in common…” This litany omits the stage text’s references to “Warburg and Schiff” – probably the banker James Warburg and New York Times owner Dorothy Schiff – while adding reference to scientist J. Robert Oppenheimer. Turner’s weakness is played upon – to convince him, Cleaver asks him the name of the man who took his livelihood away, and Turner speaks it as if now convinced by his argument: “Monty Goodman”.

The wider right-wing view of Britain in 1977 is presented; Rolfe provides a response to the famous 1962 Dean Acheson quote about Britain’s having lost an Empire and not yet having found a role: “We have found a role. As Europe’s whipping boy”. He also refers to the nation as “seedy, drab” and a “flaccid spongers’ state”. Rolfe’s views echo Robert Moss, whose book The Collapse of Democracy (1975) is quoted at the start of Act 3: “the tentacles of bureaucracy and egalitarian socialism are strangling private enterprise.”33 In the theatre text, this is placed directly before a Hitler quotation from February 1933, making an explicit analogy between Weimar Germany and 1970s Britain. Yet Edgar undermines this doom-laden vision: the scenes in the Labour Club and the Pakistani restaurant have a mood of humdrum warmth to them, indicating a contrast with “Peterhouse School” Conservativism, which Edgar associates with Rolfe’s solitary individual traits.

Significantly, left-wing Labour agent Paul’s mocking comment about Major Rolfe being “to the right of Genghis Khan” is given instead to Peter Crosby, the moderate Tory. This is part of how Edgar makes Crosby more sympathetic in the television version and a stark contrast to both the Nation Forward characters and Major Rolfe. Significantly, Crosby is given no role in Kershaw and Platt’s use of the NF members to break the picket-line; their Machiavellian actions mirror the dog-whistle cynicism of Thatcher’s “swamped” comments. However, he does benefit from this, holding the seat for the Tories – though Crosby’s moderate Conservativism would have been tested under Thatcher as the 1980s progressed.

Edgar claims the play “got some things right”: for example, Maxwell being a prototype Nick Griffin – who was first to stand for the NF in the Croydon North West by-election in 1981. But Edgar also admits that he got the involvement of big business in the far right wrong – though he includes a caveat that the anti-Common Market far right has drawn upon business support; Arron Banks and the rise of UKIP being the key current example.34

The theatrical text’s long discursive dialogues between characters on the political left are significantly truncated. The Labour Club-set Act 1 Scene 3 in the stage version contains lengthier discussions establishing the political context; this is the fifth scene in the television version. It opens with a “beer shot”, instantly foregrounding the setting as a working-class milieu. This scene also omits the Cliftons’ darts match and Clifton is dressed in a more formal and less “oldish, corduroy” suit than Edgar’s original text stated.35 Sandy’s northern origins are clearly articulated in the original; here, as played by Lloyd, she has a neutral, middle-class accent.

The theatrical text’s long discursive dialogues between characters on the political left are significantly truncated. The Labour Club-set Act 1 Scene 3 in the stage version contains lengthier discussions establishing the political context; this is the fifth scene in the television version. It opens with a “beer shot”, instantly foregrounding the setting as a working-class milieu. This scene also omits the Cliftons’ darts match and Clifton is dressed in a more formal and less “oldish, corduroy” suit than Edgar’s original text stated.35 Sandy’s northern origins are clearly articulated in the original; here, as played by Lloyd, she has a neutral, middle-class accent.

The television version reduces the lengthy scene in which Bob and Sandy Clifton discuss the campaign. Sandy is given greater agency as she provides an additional story of the discomfort of a “widow, 64” in the more multicultural Britain. This empathy for the angry, disaffected working-class voters is given fuller reign on television, with Sandy’s dialogue emphasising Labour’s core reliance on these voters. The original play’s later references to racist electors putting a “brick and a neat little pile of excreta” through the Cliftons’ letterbox are removed, making the Taddley situation less obviously like the charged campaign in Smethwick in the 1964 General Election, where Tory Peter Griffiths had won with an openly racist campaign. However, crucial local context is suggested by how Labour characters refer to Taddley as in “Enoch country”. The television version has much less focus on the Cliftons’ domesticity, removing their home as a setting and removing references to their child Ruth. This change in emphasis is perhaps surprising given the way Edgar so skilfully shows intersections between the personal and political elsewhere.

The television version reduces the lengthy scene in which Bob and Sandy Clifton discuss the campaign. Sandy is given greater agency as she provides an additional story of the discomfort of a “widow, 64” in the more multicultural Britain. This empathy for the angry, disaffected working-class voters is given fuller reign on television, with Sandy’s dialogue emphasising Labour’s core reliance on these voters. The original play’s later references to racist electors putting a “brick and a neat little pile of excreta” through the Cliftons’ letterbox are removed, making the Taddley situation less obviously like the charged campaign in Smethwick in the 1964 General Election, where Tory Peter Griffiths had won with an openly racist campaign. However, crucial local context is suggested by how Labour characters refer to Taddley as in “Enoch country”. The television version has much less focus on the Cliftons’ domesticity, removing their home as a setting and removing references to their child Ruth. This change in emphasis is perhaps surprising given the way Edgar so skilfully shows intersections between the personal and political elsewhere.

An entirely new scene is added, in which a new character, the young local militant Don Matthews, makes a rousing speech demanding that people join the picket-line.36 This speech follows an opening in which the television announcer reveals that the Tories’ majority at the previous election in Taddley was 1,127. In an echo of Turner’s opening to the Taddley Patriotic League meeting, Matthews’ delivery is faltering and nervous, with his clumsy pun falling flat and the Labour club drinkers need to be shushed to listen. He gives a stinging denunciation of “Taddley hatred” and criticises the complacency of many white workers who won’t support the Asian strikers. He refers, in New Left academic mode, to media simplification of history: “What’s the Nazis now? They’re comic bits in Colditz…” As a warning, he lists the groups the fascists would come for: blacks, Asians, Jews, Irish, the Unions and the Labour Party. He ends motivationally and colloquially: “We want you on that bloody picket-line. That’s all”.

Edgar claims that this addition was due to criticisms of the stage play – such as Radin’s argument that “some would say it was too kind” for putting the NF case “so clearly and persuasively”.37 This supposed extra focus on the right is backed up by how it is 21 minutes before the television version properly introduces any of the left-wing characters (barring Paul’s brief first appearance in 1970). Edgar’s insertion of the young militant’s speech is the playwright’s attempt to address the impression that all of the energy and drive was given to the far-right characters.

However, much else in this television version represents the left pessimistically. The key scene in which Paul and Tony are reunited, representing the contradictory left and right-wing facets of the working-class, is made notably more naturalistic on television. Paul’s sense of authority and power in the scene is reduced: instead of his cocky shouting out of the cell, “Hey, sergeant! Did you know, you got the bloody Master Race in here?” he is given the sadder, forlorn declaratives: “The bleeding Master Race… Oh, blimey…” Paul’s rhetoric is pared down; his dialogue is briefer and blunter: “Bloody ovens”.38 In the play, he has a closing, non-naturalistic address to the audience: “And, you know, it was like looking in a mirror, looking at him, me old mate […] The opposite. The bleeding wrong way round…” This scene’s ending, with Paul given the last say, is changed for television, as Tony shouts: “too good for ’em!” It is more disturbing and discomfiting, with the usually garrulous Paul cowed and silenced by his former friend and born-again fascist. Tony’s dialogue in this scene about “putting Britain first” is prescient of mainstream politics in 2017.

The television version also truncates the late scene in the Pakistani restaurant. In this scene, which is naturalistic in décor and lighting, the Cliftons, Paul and Khera discuss Patel’s arrest as an illegal immigrant. Edgar retains references to the Immigration Act 1971 but omits Khera’s pointed mentions of the history of the 1919 Amritsar massacre: he outlines how Brigadier-General Dyer had ordered troops to open fire on unarmed Indian protestors, resulting in 400 deaths.39 The television version also omits Khera’s statement that there is “more British capital in India, today, than 30 years ago”.40 It also changes the emphasis of this scene when Paul trenchantly calls for the Cliftons to choose sides. It omits his longer, more positive speech in the play about how strikers’ socialist consciousness has been raised by the strike: “Just, amid all that, some people learning. Talking, for the first time, ‘bout just how to do it, working out, quite slowly, tortuously […] But it is listening to people grow. Learning that it’s possible for them to make their future”.41 On stage, this was basically Paul’s parting shot before the election count scene. Replacing this for television, Edgar gives Paul a metaphor: “But sooner or later, Bob, you’re going to have to make up your mind which side you’re on. ’Cos you’re standing on a little pack of ice that’s floating in a sharky sea and there’s too many people on it, Bob, and the bugger’s melting away…” This new dialogue emphasises the polarised political situation that seems to exclude the moderate likes of Sandy and Bob and, perhaps, even Crosby.

This all has the effect of making the play more politically pessimistic, with less left-wing optimism – in keeping with the political mood of the later 1970s. It can even be seen as prescient of Kinnock and Blair’s moderation: Sandy, arguing for realism, seems to be more convincing than Paul, whose arguments in this scene fit Bob’s accusation that Paul sticks to his “cosy dogma”. He is a notably more left-wing Labour election agent than Bill in Melvyn Bragg’s contemporaneous novel Autumn Manoeuvres, who idolises Jim Callaghan and successfully guides his candidate to a narrow victory. Edgar’s pessimism is more prescient than Bragg’s 1978 optimism, in view of Thatcher’s subsequent electoral hegemony post-1979, though less so in terms of the far-right, which Thatcher through her “swamping” comments, and the Left through street protest, successfully repelled. Edgar argues that, by the play’s television production, the National Front were losing momentum due to the Anti-Nazi League and other anti-fascist organisations.42

The television play’s final phase contains some notable aesthetic choices. The climactic scene of the by-election count is split into two. It begins with the interior studio sequence of the count; this is much shorter than in the stage version. The Mayoress reads the vote tallies, including the increased Tory majority of 1,736 and Turner’s vote of 6,933 or 23.2% of the vote (this announcement is met with derogatory chants of “Nazi! Nazi!”). The vote is 60 lower than in the stage version, but still exceeds by 7.2% the NF’s actual strongest electoral performance: Martin Webster in the West Bromwich by-election in May 1973. Crosby begins his victory speech with an “Erm” but the scene is switched off on a television. At the Labour Club bar, Paul sadly mutters about Turner’s “seven bloody thousand” votes.

The television play’s final phase contains some notable aesthetic choices. The climactic scene of the by-election count is split into two. It begins with the interior studio sequence of the count; this is much shorter than in the stage version. The Mayoress reads the vote tallies, including the increased Tory majority of 1,736 and Turner’s vote of 6,933 or 23.2% of the vote (this announcement is met with derogatory chants of “Nazi! Nazi!”). The vote is 60 lower than in the stage version, but still exceeds by 7.2% the NF’s actual strongest electoral performance: Martin Webster in the West Bromwich by-election in May 1973. Crosby begins his victory speech with an “Erm” but the scene is switched off on a television. At the Labour Club bar, Paul sadly mutters about Turner’s “seven bloody thousand” votes.

Then, in an effective transition, we move to the play’s second exterior location sequence: this is at night, in a dark urban stairwell, lit by a streetlamp and initially seen from out of a tunnel. Paul and Khera are confronted by Tony and three unnamed NF thugs. Tony makes a racist insult – “Paul’s pet monkey” – and, as the sound of a car passes by, a fight breaks out. On stage, this fight had been more melodramatic, as it occurred at the election count itself, with crowds present. The far-right contingent is clearly portrayed as the aggressors, but Paul is far from pacifistic, picking up a broken bottle and chasing one of the men away. Onstage, he used a knife. Khera is given greater agency on television: he uses his own knife to threaten Tony, while uttering the telling dialogue that connotes Tony’s pawn-like status: “Tell me. Who do you think you are doing all this FOR?!” The scene is scarier for being in such a forbidding and naturalistically presented location.

Then, in an effective transition, we move to the play’s second exterior location sequence: this is at night, in a dark urban stairwell, lit by a streetlamp and initially seen from out of a tunnel. Paul and Khera are confronted by Tony and three unnamed NF thugs. Tony makes a racist insult – “Paul’s pet monkey” – and, as the sound of a car passes by, a fight breaks out. On stage, this fight had been more melodramatic, as it occurred at the election count itself, with crowds present. The far-right contingent is clearly portrayed as the aggressors, but Paul is far from pacifistic, picking up a broken bottle and chasing one of the men away. Onstage, he used a knife. Khera is given greater agency on television: he uses his own knife to threaten Tony, while uttering the telling dialogue that connotes Tony’s pawn-like status: “Tell me. Who do you think you are doing all this FOR?!” The scene is scarier for being in such a forbidding and naturalistically presented location.

As if in response, the television play cuts to a City of London bank, where we see in close-up “F.T. Index Prices” and “Market Prices” on BBC Ceefax on a TV screen. The next shot establishes the set, including the old Indian Mutiny painting. This final scene represents a softening of Turner, and a hardening of Major Rolfe. Turner’s line from the play is cut: “In Calcutta, bastards stoned us”, while Cleaver’s historicising reference to the Indian Mutiny being in “1857′ is retained. This links back to a speech by Colonel Chandler in the play’s opening scene (dialogue added for the television version) suggesting his greater enlightenment: “After all, it is their day, their freedom, all they fought for, hmmm…?” Turner’s lukewarm “if you say so, sir” reply prefigures his later gravitation to Nation Forward. Khera is also given the new line: “I’m a British citizen!” and we are shown Turner’s horrified reaction. At the end of the play, Turner grasps his manipulation, coming to the realisation that Rolfe’s firm, the Metropolitan Investment Trust, were behind his bankruptcy. The deflated Turner is shown to understand the real situation: that Rolfe has much more power than Goodman, and the far-right he has aligned with is in bed with City of London capitalism. We are left with the single, subtle imperative “Tell me” from Turner, in contrast to his three in the theatre text. Rolfe emerges as the powerful businessman overlord and collaborator with the demagogic Cleaver. It is Rolfe who is given the impassioned rhetoric; some of his separate lines in the play are synthesised into one sentence, as he affirms his belief in “An ideology red, white and blue in tooth and claw”.

Destiny’s afterlife and later work by Edgar and Matheson

Destiny has had a notable cultural afterlife. Commenting on the theatre version in Manchester, less than two months after the broadcast of the television version, Guardian critic David Ward argued that events had proven the points made by Destiny: “picket line punch-ups, left-right confrontations on the street, a race-dominated by-election”.43 Ward noticed that either Edgar or director Howard Lloyd Lewis had “inserted Mrs Thatcher’s now famous word ‘swamped’ into an early dialogue on immigration.”44 In another politically-charged alteration to the text, businessman Frank Kershaw’s name was changed to “Frank Ashley”, to avoid confusion with local Conservative councillor John Kershaw, who had recently attempted to halt the payment of a grant to a local theatre group “on the grounds that it was too left-wing”.

A radio version was broadcast on BBC Radio 4 on 23 July 1979 at 7:20pm, while the television Destiny was given a repeat in August 1979,45 gaining 4.4 million viewers, a higher rating than the first showing.46 Aptly, this was due to politics: specifically, the ITV strike by the EETPU and ACTT unions. This dispute over pay and overtime had started at Thames and the entire network was blacked out on 10 August – a situation that lasted for ten weeks and greatly benefited BBC ratings, from Doctor Who to Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy.47 Thus, Destiny won a somewhat small-scale “ratings battle” with BBC2, easily defeating its Sandor Vegh Masterclass (0.9m), Late News and Weather (0.9m) and Beethoven (0.2m).

In December 1983, the Monthly Film Bulletin featured Julian Petley’s review of an apparent video release of the television Destiny.48 This piece suggested that it was released on VHS in U-matic format and distributed by the BFI. It is unclear whether this was intended purely for viewing within Video Access Libraries, internal BFI purposes or commercial release.49 Indeed, it is unclear whether any release ended up happening. In his critique, Petley praises the play for avoiding being dry or using stereotypes, claiming that “Edgar captures only too clearly the very real fears and miseries which push perfectly ordinary people towards the extra-ordinariness of fascism.”50

Matheson moved away from Play for Today, citing BBC interference with her work, and went onto produce many notable television dramas, exercising her sense of “mischief” as Controller of Drama at the new Central Independent Television.51 In this role, she commissioned and produced David Leland’s Tales out of School (1983) quartet of plays which tackled issues such as contested ideals in comprehensive education – in Birth of a Nation, directed by Mike Newell –52 and the appeal of the far-right in Made in Britain.53 (Newell was later better-known for hugely successful films such as Four Weddings and a Funeral (1994) and Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire (2005).) At Central, Matheson also executive-produced Trevor Griffiths’ Oi for England, practically a companion piece to Destiny, which depicted racism and the persuasiveness of the far-right in Moss Side, Manchester.54

Edgar’s subsequent work for television included versions of stage work, like The Jail Diary of Albie Sachs,55 which he had adapted from Sachs’ autobiography and which centred on the arrest and solitary detention of the left-wing Cape Town lawyer in October 1963 by the South African authorities for suspected subversive activities. This adaptation was praised by Banks-Smith as “a simple beautiful play, raised from the personal to the universal.”56 This was followed by an epic four-part television adaptation of his successful stage version of Dickens’s The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby.57 Julian Barnes praised “the marvellous bustle” of Edgar’s script, transferred to television “without loss”.58 This involved Trevor Nunn, who also directed Edgar’s one feature film, the Tudor period drama Lady Jane (1986), whose mixed reviews singled out Edgar’s screenplay for praise.59 Edgar’s next television work was co-writing Vote for Them,60 which was shown in three episodes on Fridays at 9.30pm. The series was based on real events, in which soldiers in Cairo in 1943 set up a “mock parliament, to debate the kind of new world that they wanted to build in the peace”. Academic Neil Grant had extensively researched the Cairo Forces’ Parliament, and handed over speeches, agenda and “miles of audiotape” to Edgar to dramatise. Edgar comments on how he used dramatic license to connect “the various factual things we knew […] to make them humanly and narratively credible”, omitting the “specific roles of the actual people”, such as future Labour MP Leo Abse.61

In The Listener, Edgar discussed the process of writing Vote for Them within the context of “the recently renewed Great Faction Debate”.62 He locates his and Grant’s script within the tradition of docudrama, which uses specific historical events “as a source for treatment of general questions”, which he analogises to Shakespeare’s history plays.63 He cites Leslie Woodhead’s The Man Who Wouldn’t Keep Quiet (1970),64 about General Grigorenko’s persecution in a Soviet mental hospital, and Charles Wood’s Tumbledown,65 with its Falklands War backdrop, as exemplars of the television docudrama. He contrasts these with the drama-documentary genre, where “our interest is in the rights and wrongs of what is being represented” and there’s attention to “the credibility of the argument”.66 He gives Granada’s Invasion (1980) and Breakthrough at Reykjavik (1987)67 as exemplars of drama-documentary. Edgar argues that Vote for Them is primarily a docudrama, in its human-centred dramatising of general themes from specific events – but that it uses the drama-documentary device of having actors as older versions of the characters in the series giving “a retrospective observation on the events of their ‘fictional’ junior selves”.68 Reviewer Adam Sweeting had a mixed view of episode one, arguing that the dramatic action was “burdened with portions of undiluted social observation’ and the officer class “were rather predictably depicted as old buffers with plummy voices who play golf all the time.’69 Yet, Sweeting highlighted its interest in shedding “instructive light on the road from 1945” with the writers seeing the Cairo Parliament as a “socialist blueprint for the post-war nation”, and showing the soldiers out-arguing a Tory MP “proposing a return to ‘the free market” and choice’”. More glowing was Peter Lennon, after episode 3; he called it “splendidly directed”, “well organised” and “well written” and felt that, in a debate scene in the last episode, “the actors managed to recapture perfectly the mentality of a kind of very innocent, very generous-minded and very hopeful Englishman who appears long gone”.70

Edgar’s next television work was the single play Buying a Landslide (1992) for Screenplay,71 which depicted preparations for a US Presidential debate. Jennifer Selway described it as “an odd, nervy house-party elegantly portrayed by an all-American cast”, including Griffin Dunne and Peter Mahoney.72 His most recent work for television was the “stylised”, ideas-driven Citizen Locke (1994) about John Locke.73 Following stage plays focused on the fall of the Soviet bloc such as The Shape of the Table (1990), Pentecost (1994) and The Prisoner’s Dilemma (2001), Edgar returned to the subject of the British far-right in Playing with Fire (2005). This play was set in the early 2000s and influenced by the incremental local election gains then being achieved by the BNP in post-industrial northern “Old Labour” heartlands such as Bradford, Oldham and Burnley. This play, with its focus on the impact of globalisation and New Labour on communities outside of what Edgar has called the London “Latteland”, seems prescient of the rise in UKIP, nationalism and Brexit.74

Conclusion

Destiny has been more neglected than some Play for Today pieces. It was not included in the 1990 repeat season of Play for Today pieces on Channel 4 in 1990 that led to the canonisation of Penda’s Fen.75 Destiny was not included in Halliwell’s Television Companion (1986), despite its focus on single plays including lengthy discussions of The Right Prospectus and Penda’s Fen.76 In contrast to these and other commercially-released pieces, Destiny is an unjustly neglected Play for Today that sturdily translates an important stage play into a charged televisual representation of Britain in 1977.

Destiny received very little criticism or obstruction from senior BBC management who were largely supportive and appreciative of it, which was perhaps reflective of what Edgar has described as the “fragile armistice – even sometimes an alliance – between satirists, drama producers and documentary makers and their overlords”. Attempts to turn the BBC into a site of political and cultural opposition were at least tolerated in 1977. The radical intentions of Margaret Matheson were allowed in the case of Destiny, unlike with Scum.77 This shows something of a resurgence of the political Play for Today in 1977-78, following the fall-out from Leeds United! three years earlier. Yet, the play reflected a distinct lack of optimism within radical circles in the late 1970s, with Edgar providing a clear-sighted view of the era and accurately forecasting the left’s electoral decline. Destiny is reflective of the duopoly era when BBC television drama was, as Edgar has argued, “open to oppositional and provocative voices”. In this current era of political turbulence, significant events and shifts are going largely undramatised; in 2017, we could do with the thoroughly researched, humanistic and socially engaged dramaturgy of David Edgar on television. As the playwright has said, “to ask what a drama is telling the nation may be preferable to asking what it’s selling it.”78

Edgar claims that Destiny has had the most influence of all his plays. Particularly in its television version, it “contributed to persuading the British public that the NF was indeed a Nazi Front”. He recalls that, when he was in America and covering the 1979 UK General Election, he heard on the radio: “Whenever the (disastrous) NF vote came up, the psephological pundit would refer to it as ‘the fascist vote’. I thought, good… we won.”79

Thanks to: David Edgar and Margaret Matheson. Thanks also to Matthew Chipping (BBC WAC, Caversham), Ian Greaves, Justin Lewis, Mark Sinker, Johnny Walker and John Williams.

Originally posted: 2 June 2017 (Part 3)

Updates:

2 June 2017: minor typographical corrections and standardisation.

14 July 2017: added new paragraph and accompanying endnotes (on the video release); moved an endnote; punctuation standardisation.

Reviewing the theatre version, Michael Billington praised Di Seymour’s set, with its “towering backcloth of the Indian mutiny”, as “colourful and overpowering”. Michael Billington, ‘David Edgar’s study of the National Front transfers to London’, The Guardian, 13 May 1977, p. 10. ↩

David Edgar, ‘Racism and patriotism: should the Left be trying to recapture the idea of “One Nation”?’, The Listener, #3014, 1987, p. 44. ↩

Edgar, Plays, p. 375. ↩

Quoted in Ian Greaves and John Williams, ‘Must we wait ‘til Doomsday?’: The Making and Mauling of Churchill’s People (BBC1, 1974-75)’, Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television, Volume 37, Number 1, 2017, p. 9. ↩

Quoted in David Rolinson, ‘Women and Work: Leeds United! (1974) part 2 of 3’, British Television Drama, 31 March 2014. Accessed 28 April 2017. ↩

Greaves and Williams, p. 16. ↩

Day-Lewis, p. 15. ↩

Potter, quoted in The Art of Invective, p. 257. ↩

Edgar, Plays, p. 325. ↩

Ibid., p. 334. ↩

Ibid., p. 327. ↩

Ibid., p. 352. ↩

Ibid., p. 383. ↩

At this time in Till Death Us Do Part (1965-75). ↩

Ibid., p. 346. ↩

1915; published 1917. ↩

Edgar, Plays, p. 356. ↩

George Orwell (1942), quoted in George Orwell (Ian Angus and Sonia Orwell (eds.), The Collected Essays, Journalism and Letters – Volume 2: My Country Right or Left 1940-1943 (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1971), p. 219. ↩

Ibid., p. 228. ↩

Angus Wilson, The Strange Ride of Rudyard Kipling: His Life and Works (St Albans: Panther Granada, 1979 [1977]), p. 389. ↩

Puck of Pook’s Hill, BBC, tx. 25 September 1951-30 October 1951. This children’s serial was adapted for television by Vere Shepstone, with Jarrow-born music-hall star Wee Georgie Wood starring as Puck. ↩

Also, Frederick Treves would appear as a boarding-school headmaster in Alexander Baron’s Kipling adaptation Stalky & Co. (BBC1, 1982), a rather more establishment role than Mr Fletcher in Tightrope. ↩

It featured also in Kenneth Clark’s influential documentary series Civilisation (1969). Purcell was subject of Tony Osborne and Charles Wood’s film for Channel 4, England, My England (1995), featuring Michael Ball and Rebecca Front. Incidentally, Purcell specialist Ball also starred in Victoria Wood’s final work for television, That Day We Sang (BBC2, tx. 26 December 2014, a play based on the famous ‘Nymphs and Shepherds’ recording. ↩

Peter Ackroyd, Albion: The Origins of the English Imagination (London: Vintage, 2004), p. 442. ↩

Edgar, Plays, p. 329. ↩

Ibid., p. 332. ↩

Day-Lewis, p. 15. ↩

David Edgar, ‘What are we telling the nation?’, London Review of Books, Volume 27, Number 13, 7 July 2005, available here. Accessed 25 April 2017. ↩

Orwell (1914), collected in Orwell (1971), p. 93. ↩

At the Theatre Royal Stratford East in February 1959. ↩

As a pairing, they are almost akin to Peter Egan and Richard Briers in the 1980s sitcom Ever Decreasing Circles. ↩

Edgar, Plays, p. 375. ↩

Edgar, Plays, p. 379. ↩

Edgar, email to May. ↩

Edgar, Plays, p. 327. ↩

Edgar, email to May. ↩

Radin, p. 20. ↩

Also, Paul’s long critique of idealised Second World War propaganda images which commanded “This is your England, Fight for It” is cut. ↩

Edgar, Plays, pp. 394-5. ↩

Ibid., p. 395. ↩

Ibid., p. 396. ↩

Edgar, email to May. ↩

David Ward, ‘Destiny’, The Guardian, 16 March 1978, p. 10. ↩

Ibid. ↩

BBC1, 10.20pm, Tuesday 14 August 1979 ↩

‘Daily Viewing Barometer’, BBC Audience Research Listening and Viewing Survey, Tuesday 14 August 1979. BBC WAC. ↩

Glenn Aylett, ‘STRIKE OUT’, Transdiffusion, 3 September 2005, available here. Accessed 12 May 2017. ↩

Julian Petley, ‘VIDEO: Destiny’, Monthly Film Bulletin, Volume 50, Number 599, December 1983, pp. 339-340. ↩

As Julia Knight has detailed, the first Video Access Library was opened in 1981; these were used to distribute work by video artists and work commissioned by the Arts Council. By 1986 there were five VALs in the UK – with two in Newcastle Upon Tyne. Julia Knight, ‘High Hopes for Video: The UK Independent Film and Video Sector’s Engagement with the Videocassette’, Post Script, Volume 35, Number 3, June 2017, pp.55, 59. ↩

Petley, ‘VIDEO: Destiny’. ↩

Knight and Rayner. ↩

Tales Out of School: ‘Birth of a Nation’, Central for ITV, tx. 19 June 1983. ↩

Tales Out of School: ‘Made in Britain’, Central for ITV, tx. 10 July 1983. ↩

Oi for England, Central for ITV, tx. 17 April 1982. ↩

The Jail Diary of Albie Sachs, BBC2, tx. 23 February 1981. Written by David Edgar, produced by Alan Shallcross, directed by Kevin Billingham. ↩

Nancy Banks-Smith, ‘Natural gas’, The Guardian, 24 February 1981, p. 9. ↩

The Life And Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby, Primetime for Channel 4 in association with the RSC, tx. 7 November 1982-28 November 1982. Adapted by David Edgar, produced by Colin Callendar, directed for the stage by Trevor Nunn and John Caird, directed by Jim Goddard. ↩

Julian Barnes, ‘Smashing against “the Wall”’, The Observer, 14 November 1982, p. 36. ↩

Lady Jane featured Helena Bonham Carter as 16-year-old Lady Jane Grey, forced to marry Lord Guilford (Cary Elwes), who reigned for nine days in 1553. Derek Malcolm praised its “lively and intelligent” screenplay, acting and “a feel for the time that’s entirely commendable”, though criticised its “slow, unvarying pace” and lack of cinematic approach. – Derek Malcolm, ‘An innocent on mean streets’, The Guardian, 29th May 1986, p. 11. David Robinson agreed, highlighting the authenticity of the locations, Edgar’s studious research and how the “political machinations” are “lucidly laid out”, but argues that, as cinema, “it is rather lifeless”. Robinson also criticised how Lady Jane and Guilford as presented as “20th-century-style liberals” who “turn their nine days into a communist revolution” – David Robinson, ‘Cruel city of comedy’, The Times, 30 May 1986, p. 15. Clancy Sigal highlighted its status as “one of the largest location pictures to be mounted in Britain”, which used eleven castles. Sigal also stated it was “intermittently effective if not very plausible” and would go down well with “thinking teenagers and royal enthusiasts intrigued by the notion that for nine days England may have been ruled by a couple of flower persons”. He describes Bonham Carter and Elwes as a “teenage Beatrice and Sidney Webb“, and slates Bonham Carter’s inability to convey passion “for a man, still less a nation“ – Clancy Sigal, ‘History with the glams’, The Listener #2963, 5 June 1986, pp. 35-6. Most critical was Philip French, described it as “a dull costume drama’, finding the “socialists before their time” theme far-fetched: “About the only things they didn’t ask for were abortion-on-demand and a day-time crèche in the Tower of London for ladies of the bedchamber and aristocrats awaiting education.” – Philip French, ‘Pulping the Yuppie’, The Observer, 1 June 1986, p. 21. ↩

Vote for Them, BBC Birmingham for BBC2, tx. 2 June 1989-16 June 1989. Written by David Edgar and Neil Grant, produced by Carol Parks, directed by James Ormerod. ↩

David Edgar, ‘Faction Plan’, The Listener #3116, 1 June 1989, p. 13. ↩

Ibid., p. 13. ↩

Ibid., p. 16. ↩

The Man Who Wouldn’t Keep Quiet, Granada for ITV, tx. 24 November 1970. Produced and directed by Leslie Woodhead. ↩

Tumbledown, BBC1, tx. 31 May 1988. Written by Charles Wood, produced by Richard Broke, directed by Richard Eyre. ↩

Edgar, ‘Faction Plan’, p. 16. ↩

Breakthrough at Reykjavik, Granada for ITV, tx. 6 December 1987. Written by Ronald Harwood, produced by Norma Percy, directed by Sarah Harding. ↩

Edgar, ‘Faction plan’, p. 17. ↩

Adam Sweeting, ‘Squeezing a laugh out of rock’, The Guardian, 3 June 1989, p. 21. ↩

Peter Lennon, ‘Democracy’s Last Stand’, The Listener #3119, 22 June 1989, p. 38. Writing in Thatcher’s penultimate year in power, Lennon argued that “its topical value has not yet fully sunk in. It would be worth an early repeat”. Sadly, this intriguing drama has not been repeated once in the subsequent twenty-eight years or been commercially released. ↩

Screenplay: ‘Buying a Landslide’, BBC2, tx. 2 September 1992. Written by David Edgar, produced by Chris Parr, directed by Simon Curtis. ↩

Jennifer Selway, ‘TV & RADIO’, The Observer, 30 August 1992, p. 65. ↩

Citizen Locke, Bandung Productions for Channel 4, tx. 30 April 1994. Written by David Edgar, produced by Tariq Ali, directed by Agnieszka Piotrowska. This was from the same production team as Derek Jarman’s Wittgenstein (1993); it featured John Sessions as John Locke and was directed by the Warsaw-born Agnieszka Piotrowska. Edgar had initially wanted to a do a play about Hegel for this philosophers’ series but his interest in Locke was whetted by his wife Eve Brooke, a Birmingham city Labour councillor, who had written a thesis on Locke. – Jennifer Selway, ‘Locke, stock, trouble’, The Observer, 24 April 1994, p. C16. Edgar described Citizen Locke as a “work play”, based on ideas, and not a biopic; Selway saw it as a “play being pulled in different directions”, with Piotrowska wanting more explicit sexual content, but mentions that commissioning editor Karen Brown cut a shipboard kiss to make it more implicit. Edgar is said to have “hated” a dream sequence where dancers were used to visualise sexual torment that Piotrowska thought was in Locke’s head. Selway reported that the Polish director fondly regarded Edgar as a “typical repressed British male”. ↩

Edgar, ‘My fight with the Front’. ↩

This repeat season, titled Films 4 Today, focused on filmed work that it connected with Film on Four via David Rose. ↩

Leslie Halliwell and Philip Purser used a star rating system to judge the value of past television programmes: “one to four asterisks denoting the extent of its social/historical/artistic interest” – Leslie Halliwell and Philip Purser, Halliwell’s Television Companion, second edition (London: Paladin, 1985), p. xx. This book, due to Purser’s influence, contains much focus on single plays. It gives ‘The Right Prospectus’ a *** rating and Penda’s Fen none – Ibid., p. 523. ↩

Edgar, ‘My fight with the Front’. ↩

Ibid. ↩

Edgar, email to May. ↩

Pingback: ‘An ideology red, white and blue in tooth and claw’: David Edgar’s Destiny (1978) – Part 2 of 3

Pingback: David Edgar’s Play for Today DESTINY (1978) – 3-part essay on British Television Drama website – Opening Negotiations