by DAVID ROLINSON

After passing away in late April, writer John Sullivan (1946-2011) was paid tributes by many people from different walks of life, who reminisced about his great shows and great moments. Inevitably the long-running Only Fools and Horses (1981-2003) was central to those tributes, as so many of us remember visits to the Nag’s Head like reunions with friends, and can trace our lives with memories not just of the show but of the circumstances in which we watched it. Sullivan wrote some of television’s finest and most popular comedy series, but even that isn’t high enough praise. Sullivan’s best work belongs in the lineage of the great writers who inspired him, such as Johnny Speight and Ray Galton and Alan Simpson. Like them, Sullivan reflected everyday life back at his audience with respect for their experience and intelligence, and the audience’s recognition of truth produced not only laughs for his one-liners and set-pieces but also an emotional commitment and sense of social awareness of the kind critics usually associate with genres other than this less critically-respected popular form. He was a television writer in its purest sense, and in the ways by which we define key television playwrights: he mastered a genre whilst refining its capabilities and playing to his audience’s awareness of its functions, and for a while became as visible a “name” – whose credit on a programme produced certain expectations – as any more vaunted auteur. At his peak – surely the 1980s, given that unbroken run of success that included the early years of Only Fools and Horses plus Just Good Friends (1983-86) and Dear John (1986-87) – he changed the way we speak to each other.

Born into a working-class family in Balham, South London, Sullivan left school at 15 with no qualifications, though he had enjoyed writing and had a love for Charles Dickens, who “was writing about areas that I knew about and the class system that was familiar to me”.1 He often talked about the inspiration of his family, particularly his father, a plumber with a hatred for the class system that was heightened by his spell in a prisoner of war camp. Sullivan’s childhood, family and pre-fame experiences fed into his writing. This goes beyond characters being drawn from real people, and into dynamics that run through his work: family relationships, generational tensions and political positions, and how they impact on dialogue, and especially – harder to describe than it is to experience – atmosphere. He drew from experience, honing real incidents into classic set pieces, such as the chandelier incident (in Only Fools episode ‘A Touch of Glass’), which had befallen his father with less comic consequences.

As Sullivan told Steve Clarke, he was typical of working-class kids who “wanted to get out and earn some money to help the family out”, and though he took the 11-Plus “it never seemed to matter if we passed or not because we were all going to work in factories anyway”.2 Writers and producers in light entertainment and comedy offer a neglected alternative narrative to the well-known history of British television drama practitioners of the same period who came from working-class backgrounds, passed their 11-Plus and moved through grammar school and University before seeking out television as an anti-elitist mass medium. The likes of Dennis Potter and Tony Garnett discussed the tensions in their formal separation from their class experience, and it motivates their work in very different ways. In comedy, Speight, Galton, Simpson, Sullivan and others spoke from within that experience. It is unsurprising that Steptoe and Son (1962-74) had such an impact on Sullivan: “I suddenly realised what you can do with comedy, because it was so funny and just filled with drama and pathos”. Steptoe was to have a profound impact on early Only Fools, in the sense of being trapped by family circumstances (“You suffocate me”) either because they are frustratingly unable, or complexly unwilling, to escape. The conventional sitcom format reinforces that to an extent: hence Raymond Williams’s shift from highly praising Steptoe and Son’s first episode to worrying, in the 1970s, that the series form “prevents any full working-through” of its issues, a statement that I’ve compared with academic work on the form’s alleged conservatism.3

Sullivan’s early jobs included working as a messenger for Reuters and for the advertising agency that David Puttnam and Alan Parker worked for, but more lucrative work followed: cleaning cars, plumbing, or working for a brewery, during the latter of which Sullivan co-wrote a script (after Paul Saunders learned that Speight earned £1,000 per script). Although rejected, their joint script Gentlemen, with an Ealing-sounding set-up (an old-fashioned establishment under threat from a more polished but hollow rival), seems to have recognisable Sullivan elements: aspiration in limiting circumstances, a dignity in labour/community and, in the ex-soldier clinging to a role in a dingy environment, the seeds of the much later Heartburn Hotel (1998-2000).

Going it alone, Sullivan sought further education, both in classes (shades of Rodney) and in television. Having had numerous script rejections, he tried to learn more about television by applying (in 1974) for a job at the BBC. His jobs included props and scene-shifting: he helped put down the waterproofing and kerbstones for the Morecambe and Wise Singin’ in the Rain homage (Christmas 1976). The popular narrative of Sullivan going from scene-shifter to scriptwriter is only partly true: already a (failing) writer, the job was a way in, as he exploited this position to approach producers and stars, gaining commissions for The Two Ronnies (1971-87) and the 1977 pilot that led to four series of Citizen Smith (1977-80).

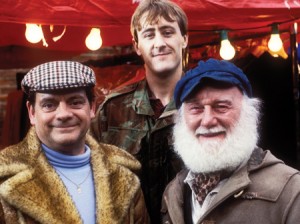

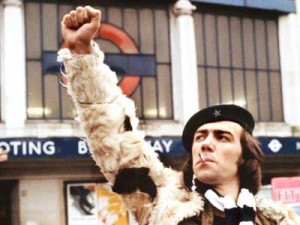

Sullivan’s work skilfully underscores reality with surrealism/the absurd. It’s there in the memorable dialogue in his Sid and George sketches for The Two Ronnies. David Quantick rightly picks one out: “The scene where Sid, in a rare moment of existential doubt, asks George what the point of life and human existence is, and receives the reply, ‘Something to do, I suppose,’ would make Beckett envious.”4 It’s in Citizen Smith, where the conflation of social observation and outright absurdity in Wolfie Smith’s actions for the Tooting Popular Front is grounded in the frustrated aspirations of a dreamer, whose personal relationships bring him up against different models of working-class experience and masculinity. Sullivan’s follow-up Over the Moon (1980), with another aspiring dreamer, this time a football manager, got as far as a pilot and script commissions before the plug was pulled, and there was little initial enthusiasm for what became its follow-up, Only Fools and Horses…

Sullivan’s concept of a sitcom based around “pubs, clubs and tower blocks”, in “a modern, vibrant, multi-racial new slang London where a lot of working-class guys had suits and a bit of dosh in their pockets”, would be focused around wheeler-dealers of the type experienced by Sullivan and producer Ray Butt (whose own story is fascinating; his dad had a stall on the Roman Road, where Tommy Cooper “used to sell saccharine and elastic”). The BBC had already rejected this idea when ITV started Minder. “Shit. That idea’s gone,” thought Sullivan, who was “choked because I thought they’d done that modern London”. Even when the series got the go-ahead, it was subject to much negotiation and its future questioned, especially after the relative failure of its first season.

Of course, Only Fools became a ratings juggernaut, a weapon against the BBC’s critics, and part of the attempt to construct a promotional brand through the repetition of “iconic” moments: Ricky Gervais dancing, Basil Fawlty thrashing a car, “Del falling through the bar”, all moments designed not only to trigger memory of the programmes but of the mode of transmission, of communal viewing in a fragmenting media landscape. But the moments were so removed from context that they’re almost a negative shorthand, and Del falling through the bar has been much parodied. It is one of the finest moments in British television history, but that’s because of context. The fall itself was not the joke – having witnessed a less dramatic version of this incident in a pub, Sullivan held onto the idea for years until finding the right context. ‘Yuppy Love’ (1989) puts political discourse about social mobility against the realities of the class system. Rodney is trying to go up in the world through education, and meets the higher-class Cassandra, while Del goes for the surface elements, in his yuppy makeover referencing Oliver Stone’s Wall Street (1987). Del may call yuppies his sort of people, but they sneer at his dropped aitches. Del and Trigger are already floundering in this environment before the fall: my favourite part of that scene comes when Trigger, encouraged to “talk about money” to City types, says, “I saw one of them old five pound notes the other day”. The fall symbolises how out-of-place they are, how unfamiliar with the terrain, and how dependent on a form of support that, it transpires, isn’t there. Yes, it’s a great stunt, superbly planned (the surprise heightened by the lack of cuts as we get a single developing shot – ironically, refusing to separate it as a moment) and performed (even David Jason’s hair is funny). As Quantick put it, “the moment manages to puncture Del Boy’s dignity while highlighting his nervousness outside his comfort zone, and is also side-cripplingly funny. Which is not bad for a five-second sight gag.”5

The BBC-heritage branding of Del’s fall could even seem unintentionally ironic. That joke came eight years into Only Fools – its effect depends on our knowledge of those eight years, and its very existence depends on the BBC’s support of the show during its lean years. Therefore, BBC’s self-congratulatory use of it – to signal their support for comedy – seems justified. However, by the time that campaign ran, it was normal for failing new sitcoms to be pulled from the schedules and replaced by repeats of Only Fools (from the early years, when it was facing a similar fate). Countless series fell through the bar. And in his later years, the BBC was to press for an ill-advised Only Fools comeback after the satisfying ending in 1996, and made Only Fools spin-offs such as The Green Green Grass (2005-2009) and Rock & Chips (2010-2011), rather than original Sullivan projects.

The BBC’s dependence on Only Fools, and the once-pervasive repeat seasons, were understandable. Yes, it plays rightly on nostalgia: when I remember great moments from Sullivan’s 1980s work, it’s in the context of shared family laughter and recitation at school, and when as many as 24 million people have the same warm memories, this is clearly a very special writer. There are too many moments to list, from Cwying in ‘Stage Fright’ (1991) and Peckham Spring in ‘Mother Nature’s Son’ (1992) to the dubious leisure merchandise in ‘Danger UXD’ (1989). The repeats stood up, and will continue to do so. And like repeats of Till Death Us Do Part (1965-75) and Steptoe and Son, they’ll take on more of a sense of social documents. Comedy is an important part of television social realism, and I’ve recently included sitcoms, from Steptoe and Son to Rab C Nesbitt (1988- ), in a long chapter on the history of TV social realism.6

Stephen Wagg discusses Del (“culturally working class, but technically working for himself”) and the show in the context of the 1980s, and notes how Del’s flash style owes much to Sullivan’s “visit to a pub in the Old Kent Road in the late 1970s ‘to find that the tough guys with callouses on their knuckles, who used to like a pint, were now sipping umbrella-topped cocktails’.”7 As Wagg notes, the docks are declining, and community too, though Del’s world survives riots. The show’s politics are often fascinating. Del may be a Thatcherite, but the sitcom form means those values constantly fail, and thanks to Sullivan’s inspired schemes, often seem absurd. Those values are often challenged, sometimes by Rodney but by the show itself in ‘He Ain’t Heavy, He’s My Uncle’ (1991), when Uncle Albert visits the yuppified docklands developments where his birthplace used to be. As a Thatcherite, Del is in favour of the development, but while he speaks, Albert and Rodney walk away from him – it’s an unresolved moment with no comic outcome. The scene throws up all kinds of associations. Del’s speech is a bitterly ironic inversion of the lament for working-class unity in the last episode of Alan Bleasdale’s Boys from the Blackstuff (1982), and the fact that Albert’s birthplace was called Tobacco Road brings to mind Erskine Caldwell’s book Tobacco Road (1932, filmed in 1941 by John Ford). In Only Fools, there clearly is such a thing as society.

So there is anger in Only Fools, and moments of heartfelt drama. There is Grandad’s lament in ‘The Russians Are Coming’ (1981) that instead of “homes fit for heroes”, Britain produced “heroes fit for homes” (a scene that wears its Steptoe influence on its sleeve). There is ‘Strained Relations’ (1985), a raw and superbly-handled episode in which Grandad is buried, after the recent death of the peerless Lennard Pearce. Del opening up about how much of his bluster is performance puts much of the rest of the series in a different light. The move to 50-minute episodes gave more time for supporting characters, more breathing space for plots, and more scope for characterisation in a more overtly comedy-drama format which, like the best soap, allowed the Trotters’ lives to change in ways that mirrored changes in society and in families watching. There’s been academic debate on what Lez Cooke has described, in a piece on Clocking Off (2000-2003), as “the new social realism”, as single plays gave way in the 1990s onwards to series, there followed “a postmodern shift in the representation of social realism in twenty-first-century television drama”, as the concerns of single plays embraced different stylistic influences and hybridised with other forms such as soap8 I can’t help thinking that Sullivan’s work could be seen in that context. Of course, placing sitcom within debates on television drama is nothing new – aiming to explore ‘the boundaries of genre’, a section of Popular Television Drama: Critical Perspectives includes chapters on Butterflies (1978-83) and Dad’s Army (1968-77). I’ve written recently on how The Royle Family “develops a new sitcom-realist hybrid”, but perhaps the sitcom-tragi-soap elements of Only Fools make Sullivan’s work a neglected case study.9

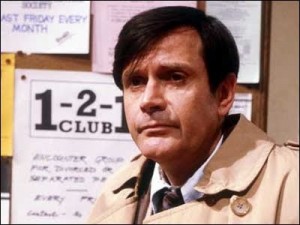

Only Fools connects, but even without that, Sullivan leaves a great body of work. As well as Citizen Smith, there’s the hit Just Good Friends, a romantic comedy in a different world (albeit playing on class tensions) with a strong female lead as Sullivan addressed concerns (notably from Citizen Smith’s Cheryl Hall) that he didn’t write women well. Dear John is one of my favourite sitcoms, and its American remake ran in decent slots on BBC1 as well. The skill as a dramatist which was so vital to his comedies found an outlet in comedy-drama such as Over Here (1996) and Micawber (2001), which also provided an outlet for his love of Dickens, though this angle on David Copperfield only emerged on ITV after an acrimonious falling-out with the BBC. The sense that comes across in the 1996 climax of Only Fools, of changing social status and financial success impinging on ducking and diving, comes across in other work too: Sitting Pretty (1992-93) for instance, or elements of Rock & Chips and The Green Green Grass. But The Green Green Grass shows that, even in Sullivan’s supposedly lesser work, there are moments of comedy gold. Comedy-drama Roger Roger (1996-2003) contains many of my favourite Sullivan moments, and in the Bodyguard joke, one of my favourite Sullivan gags. It’s unfortunate that Heartburn Hotel (co-written with Steve Glover) is trapped in the body of a studio sitcom (on which terms it’s patchy at best), as there’s a fascinating, bitter comedy drama in there somewhere. It places a left-wing dreamer against a right-wing realist/brutalist – nothing new there, it was a feature of Only Fools and Citizen Smith, in their twist on Galton and Simpson pairings such as Tony Hancock and Sid James in Hancock’s Half Hour (1956-61) and Harold and Albert Steptoe. However, if early Only Fools had a surprisingly nasty edge, Heartburn Hotel is at times unpleasant, but the shabby little-Englander setting and critique at work (the situation stemming from the Falklands and from a British Olympic bid) reminds us that Only Fools did not always share the worldview of some of the tabloids who endorsed it.

To be fair, tabloid critics were sometimes more astute reviewers of Sullivan’s work than broadsheet critics. I say this not to generalise about critical resistance to popular forms (there are exceptions), but to note that the tendencies and movements which broadsheets rushed to label neglected the type of studio situation comedy at which Sullivan excelled. The sophistication of Only Fools lies in its writing and performance, in storytelling craft, an ear for dialogue and its grounding in a community, rather than in format. It does not need faux-docusoap style to signpost the relationship with reality at the heart of its comedy of recognition. Maurice Gran has compared Sullivan’s work with modern TV comedy that “aims for irony and ends up snide and charmless”, especially “pseudo-documentaries” copying The Office (but “without the talent of Stephen Merchant and Ricky Gervais”), which “end up unkind”.10

With Sullivan, we don’t sit at a superior remove from characters at whose behaviour we cringe. We watch with affection, and as part of the community derive pleasure from well-turned phrases, well-told anecdotes and superbly-crafted incident. Though Sullivan moved towards creating and overseeing (for instance, on The Green Green Grass), his work disproves the broadsheet favourite call for British comedies to be written along the American model, with gangs of gag writers. Sullivan was a skilled gag-writer (Grandad in Only Fools: “I’ve had lots of sobering thoughts in my time. That’s what started me drinking”), but there is in his best work an organic connection of characters, jokes and incidents that is the result of craft, and evidence of a great television writer. Bonjour.

Originally posted: 8 September 2011.

[This piece first appeared on the This Way Up website on 9 May 2011. It is presented here with revisions, new material and endnotes.]