by DAVID ROLINSON

Play for Today Writer: Roy Minton; Producer: Mark Shivas; Director: Alan Clarke

“This place gets more like a bleeding madhouse every day…”

Funny Farm depicts a night shift by nurse Alan Welbeck (Tim Preece) on a psychiatric ward. As reviewer James Scott put it, the play comments on “conditions in our mental hospitals – understaffing, overwork, bad pay, old inadequate buildings” and unsatisfactory “patient treatment and cure”, points which are heightened by the play’s “understatement” and rejection of “sensationalism and sentimentality”.1 Dennis Potter praised this “gentle and observant drama” as “Beautifully acted, compassionately written and intelligently directed”.2 The play also dramatises writer Roy Minton’s contention that “Psychiatric therapy is fundamentally an agent for the state”,3 and provides an example of Minton’s productive collaboration with director Alan Clarke. My book Alan Clarke didn’t have a chapter on Funny Farm in its own right – I discussed it only in relation to other collaborations and tendencies across Clarke’s work. This essay aims to correct that omission, and features some new research findings.

Funny Farm depicts a night shift by nurse Alan Welbeck (Tim Preece) on a psychiatric ward. As reviewer James Scott put it, the play comments on “conditions in our mental hospitals – understaffing, overwork, bad pay, old inadequate buildings” and unsatisfactory “patient treatment and cure”, points which are heightened by the play’s “understatement” and rejection of “sensationalism and sentimentality”.1 Dennis Potter praised this “gentle and observant drama” as “Beautifully acted, compassionately written and intelligently directed”.2 The play also dramatises writer Roy Minton’s contention that “Psychiatric therapy is fundamentally an agent for the state”,3 and provides an example of Minton’s productive collaboration with director Alan Clarke. My book Alan Clarke didn’t have a chapter on Funny Farm in its own right – I discussed it only in relation to other collaborations and tendencies across Clarke’s work. This essay aims to correct that omission, and features some new research findings.

The play was officially commissioned as a Play for Today by producer Mark Shivas on 31 May 1974, as a 75-minute drama (a fact that would later become problematic). Minton signed his contract on 13 June; the target delivery date was 31 July; it was delivered on 27 August and accepted on 16 September.4 On 13 November, Shivas requested an additional payment for Minton (okayed on 19 November) on the basis that he “will be attending rehearsals and recording” from 23 November to 19 December, although when the request was okayed the end date was given as 11 December.5 Shivas stressed that Minton’s “presence is quite necessary”, an indication of the work required or of the collaborative process that Minton enjoyed with Clarke, who was still at this stage very much a writer’s director. The relevance of this close collaboration will become apparent. The play was ultimately transmitted on 27 February 1975.

Like Minton’s Scum – or, indeed, Scrubbers, a film to which he was just one, unhappy, contributor – Funny Farm has a title that is unsettlingly direct, confronting perceptions. “In two words Roy Minton sums up most people’s views of the mental hospital”, argued Scott. “Madness scares the hell out of us, so we feel compelled to make bad jokes about “the looney bin”, “the laughing academy” or, ‘the funny farm’.”6 Patients use gallow humour themselves in the play, as in Arthur’s observation – and variations on it – that “This place gets more like a bleeding madhouse every day”. The title also predicts the strain of humour in the play, in dialogue, interactions and grim repetitions of unsettled behaviour, as Welbeck experiences – in Minton’s words – “the tears, the vacancies, the obsessions” of his patients.7

The setting – as so many medical dramas know – affords the placing together of various personalities from various backgrounds, but in this play their specific psychiatric conditions are not the pretext for diagnosis. They have meetings with a specialist, but we are not privy to them – instead, we follow nurse Welbeck and his routine on the ward, and experience their varied behaviour during his visits or in their own conversations. The characters include Les, who claims that his nerves were damaged in military service, and who is now dedicated to exercise: “You’ve got to be perfect”. Jack’s promotion to suited office work seemed to trigger a collapse (“I don’t know what happened to me”), while serious teenage illness seemed to have a lasting mental impact on Walter, whose overt generosity and helpfulness gives way to a hysterical bid for freedom. There is the aged Mr Scully, experiencing advancing dementia; and Sidney, who never recovered from dismissal from his gardening job and cottage after requesting more pay from a boss whose inherited wealth means that he, Sidney stresses, had never worked a day in his life. Others include Mr Chadd, who constantly bursts into song and asks others to moderate their language; Jonathan the self-challenging artist; Graham the chess obsessive; and Jeff the Elvis fanatic who, in Arthur’s words, is often “giving it some fist in the wanking pit”. Listing characters like this, and noting that their differences will produce interplay, might bring to mind the likes of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (released later in 1975), Dennis Potter’s Emergency Ward 9 engagement with hospital soaps, or even the sitcom Only When I Laugh (1979-82). Its state-of-the-nation concerns evoke the concept, though not the execution, of Britannia Hospital (1982). However, let’s stop this list now while it still resembles context: Funny Farm is a very different piece, with a sparseness and concern with institutionalisation that is characteristic of the work of Minton and Clarke in this period, separately and in collaboration. Its subject matter makes it clearly a Play for Today and a play for today.

Arthur is the most complex of all the patients. He seems to be an identification figure, providing sardonic insights, but we realise that he is an alcoholic, who is at (or beyond) his last chance, and anxious about his prospects when he is potentially allowed to leave: “What the hell’s gonna happen?” Although he is aware of the impact of his condition on his wife and others, and tactful when other patients offer bland advice unaware of the nature of the condition (“What about a hobby?” “I’ve got one”), he is fatalistic about the lack of a cure for his liver and, possibly, his mind. He gets an unwelcome reminder when the ward is invaded by bullying recidivist James, who arrives drunk and demanding special treatment on the basis that he can pay. Friends and colleagues of Minton have connected the depiction of these issues with Minton’s initial trigger for writing the play. In Richard Kelly’s interview book Alan Clarke, Paul Knight recalled that in “about 1969” he and Minton’s then-wife committed Minton, who was experiencing alcoholism and gambling issues, to a mental home “because that was the only course – he was in a terrible state”. They put him in an “enormous and incredibly grim fortress-like Victorian building”, until Minton rang, at four that morning, to say: “Get me the fuck out of here.” Knight argues that, since Minton’s writing was often “based on his life”, “I suppose there was a bit of that episode in Funny Farm.”8

Arthur is the most complex of all the patients. He seems to be an identification figure, providing sardonic insights, but we realise that he is an alcoholic, who is at (or beyond) his last chance, and anxious about his prospects when he is potentially allowed to leave: “What the hell’s gonna happen?” Although he is aware of the impact of his condition on his wife and others, and tactful when other patients offer bland advice unaware of the nature of the condition (“What about a hobby?” “I’ve got one”), he is fatalistic about the lack of a cure for his liver and, possibly, his mind. He gets an unwelcome reminder when the ward is invaded by bullying recidivist James, who arrives drunk and demanding special treatment on the basis that he can pay. Friends and colleagues of Minton have connected the depiction of these issues with Minton’s initial trigger for writing the play. In Richard Kelly’s interview book Alan Clarke, Paul Knight recalled that in “about 1969” he and Minton’s then-wife committed Minton, who was experiencing alcoholism and gambling issues, to a mental home “because that was the only course – he was in a terrible state”. They put him in an “enormous and incredibly grim fortress-like Victorian building”, until Minton rang, at four that morning, to say: “Get me the fuck out of here.” Knight argues that, since Minton’s writing was often “based on his life”, “I suppose there was a bit of that episode in Funny Farm.”8

Whether or not the play echoes Minton’s life, its themes certainly echo other Minton dramas. For example, Funny Farm draws correlations between the ward, the military and society, in keeping with the concern with institutionalisation that runs through a lot of Minton’s work. For instance, Scum is said to have developed as part of an unrealised trilogy of plays about institutionalisation in the police, the army and Borstal.9 Ted describes life in this institution as being “Just like the forces. Good mates, comradeship.” Arthur invokes the army in a vitriolic response to Mr Chadd’s reminiscence about his lost friends in the trenches in the First World War. Mr Chadd misreads Arthur’s statement “then you’re one of the stalwarts who helped to make us the nation we are today” as friendly interest, but Arthur’s explanatory follow-up is brutal: “you’re one of the bastards to blame for the mess we’re in […] How dare you go winning wars […] You sit there canting bullshit about flags, orders and death […] yet there is not one solitary opinion about your boring cadaverous person. They should not have died.” Today’s youth, Arthur believes, “won’t go hurling themselves on rusty bayonets for any half-baked reason” like Mr Chadd and his “brainwashed mates”. Meanwhile, Les says that his “nerve went” during his time in military service, and he is now constantly moving as if movement is a displacement activity, physical activity that will occupy his mind.

These ideas echo an earlier Minton play also directed by Clarke, the playful Stand by Your Screen.10 In that play, Christopher Gritter (John Neville) is at home, not a hospital, but he is arguably still in an institution because his family has internalised social attitudes and pressures.11 Gritter hides behind screens in the living room, rejects traditional lifestyles and makes the class-conscious statement to-camera that “If you’re poor, you’re mad; if you’re rich, you’re eccentric.” Gritter’s prior breakdown is connected with institutionalisation, through his National Service, in which he was taught to kill without understanding why: “I am told not to think, but to do.” If his movement – ending the play running on the spot, in suit and slippers – anticipates Les’s later activity in Funny Farm, Gritter’s statement to his mother directly anticipates the later play: “Mummy, Mummy, where is the womb? The security and comfort, the inside better than the outside of the womb? Mother, why did you let me go? Why did you spew me out with that enormous shudder of pain and ecstasy into this temple of darkness?” Minton used the same imagery while promoting Funny Farm: “Hospitals provide a womb for a while. But the end result is debilitating. The recidivism is enormous.”12 The inevitability of recidivism is a feature in Funny Farm – from James’s belligerence to Arthur’s doubt – and for the trainees in Scum, but it is also a feature in Clarke’s work without Minton, such as Clarke’s previous Play for Today, A Follower for Emily written by Brian Clark.13 There, residents of an old people’s home return early from honeymoon to be in that safe environment.

These ideas echo an earlier Minton play also directed by Clarke, the playful Stand by Your Screen.10 In that play, Christopher Gritter (John Neville) is at home, not a hospital, but he is arguably still in an institution because his family has internalised social attitudes and pressures.11 Gritter hides behind screens in the living room, rejects traditional lifestyles and makes the class-conscious statement to-camera that “If you’re poor, you’re mad; if you’re rich, you’re eccentric.” Gritter’s prior breakdown is connected with institutionalisation, through his National Service, in which he was taught to kill without understanding why: “I am told not to think, but to do.” If his movement – ending the play running on the spot, in suit and slippers – anticipates Les’s later activity in Funny Farm, Gritter’s statement to his mother directly anticipates the later play: “Mummy, Mummy, where is the womb? The security and comfort, the inside better than the outside of the womb? Mother, why did you let me go? Why did you spew me out with that enormous shudder of pain and ecstasy into this temple of darkness?” Minton used the same imagery while promoting Funny Farm: “Hospitals provide a womb for a while. But the end result is debilitating. The recidivism is enormous.”12 The inevitability of recidivism is a feature in Funny Farm – from James’s belligerence to Arthur’s doubt – and for the trainees in Scum, but it is also a feature in Clarke’s work without Minton, such as Clarke’s previous Play for Today, A Follower for Emily written by Brian Clark.13 There, residents of an old people’s home return early from honeymoon to be in that safe environment.

Arthur’s fears of recidivism are particularly important to the play’s concerns because they are tellingly exposed in a conversation with Welbeck. It is as though patient and nurse alike fear their ability, and desire, to leave the institution. Indeed, Welbeck, for all his hard work and clear dedication – he says that he likes the job, he enjoys helping people – has written a resignation letter. His reasons for leaving bring to our attention the problems with the profession that James Scott itemised in the first paragraph of this essay.

Arthur’s fears of recidivism are particularly important to the play’s concerns because they are tellingly exposed in a conversation with Welbeck. It is as though patient and nurse alike fear their ability, and desire, to leave the institution. Indeed, Welbeck, for all his hard work and clear dedication – he says that he likes the job, he enjoys helping people – has written a resignation letter. His reasons for leaving bring to our attention the problems with the profession that James Scott itemised in the first paragraph of this essay.

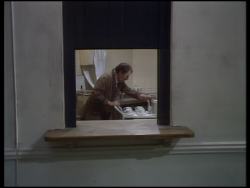

During his shift, Welbeck is asked to help on a geriatric ward – which he does, uncomplainingly attending to a patient’s basic, increasingly intimate needs – but makes it clear that his ward is already understaffed (with only two of its supposed five staff), which he says is not “fair either to us or the patients – they’re supposed to be under observation”. The sardonic reply to his question “What would you tell an inquiry?” is, “Which one?” Understaffing and overwork are key issues, as Shiva Naipaul summarised in his Radio Times preview of the play: “One patient has to be dressed, another to be spoon-fed, another to be cleaned, another to be comforted, another to be entertained, another to be rebuked” – but the nurse is the “bridge between the patient and his possible ‘cure'”, and consultants “often entirely dependent on” their information.14 Patients compete for Welbeck’s time in various scenes, attempt to help each other, or sit in boredom in the sitting room not watching the television. A female patient, Joyce, wanders in disruptively from another ward. Interviewed by Naipaul, Minton observed that “There are only the briefest of confrontations between him and the patient. He is always aware of the queue.”15 Alan Clarke added, “There should be the possibility of friendship – genuine friendship – between nurse and patient. Of course, that happens now – but not to the extent that it should. There ought to be a one-to-one ratio. One patient to one nurse. It is impossible for anyone to cope with all that distress.”16 This is one of the areas covered by the captions shown at the end of the play, which tell us that in cases of non-psychiatric illness “There are 121 nurses for 100 patients” but in cases of psychiatric illness “There are 36 nurses for 100 patients”. The Radio Times preview repeats this information and adds that the ratio between consultants and patients is 1 per 31 patients and 1 per 154 patients respectively. The preview adds other contextual information, including the fact that 65% of “British mental hospitals were built before 1891.”17

During his shift, Welbeck is asked to help on a geriatric ward – which he does, uncomplainingly attending to a patient’s basic, increasingly intimate needs – but makes it clear that his ward is already understaffed (with only two of its supposed five staff), which he says is not “fair either to us or the patients – they’re supposed to be under observation”. The sardonic reply to his question “What would you tell an inquiry?” is, “Which one?” Understaffing and overwork are key issues, as Shiva Naipaul summarised in his Radio Times preview of the play: “One patient has to be dressed, another to be spoon-fed, another to be cleaned, another to be comforted, another to be entertained, another to be rebuked” – but the nurse is the “bridge between the patient and his possible ‘cure'”, and consultants “often entirely dependent on” their information.14 Patients compete for Welbeck’s time in various scenes, attempt to help each other, or sit in boredom in the sitting room not watching the television. A female patient, Joyce, wanders in disruptively from another ward. Interviewed by Naipaul, Minton observed that “There are only the briefest of confrontations between him and the patient. He is always aware of the queue.”15 Alan Clarke added, “There should be the possibility of friendship – genuine friendship – between nurse and patient. Of course, that happens now – but not to the extent that it should. There ought to be a one-to-one ratio. One patient to one nurse. It is impossible for anyone to cope with all that distress.”16 This is one of the areas covered by the captions shown at the end of the play, which tell us that in cases of non-psychiatric illness “There are 121 nurses for 100 patients” but in cases of psychiatric illness “There are 36 nurses for 100 patients”. The Radio Times preview repeats this information and adds that the ratio between consultants and patients is 1 per 31 patients and 1 per 154 patients respectively. The preview adds other contextual information, including the fact that 65% of “British mental hospitals were built before 1891.”17

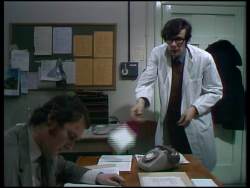

Another reason given by Alan Welbeck for his resignation is his pay: Alan Clarke told Naipaul that “The pay of the nurses is awful. Really terrible”.18 Welbeck bikes to work because he can’t afford a car or the bus fare, and worries about being able to provide for his wife and two children, concerns that are unpleasantly emphasised by James waving money at him – his claim that “I can buy you any time” is timed particularly badly for Welbeck – and Joyce shouting “tight-fisted bastard!” after him, although that is one of her universal accusations. Welbeck feels the need to leave a job that he enjoys – and there is a brutal irony in his intended alternative. He has discovered that he can earn twice as much working in a factory, but as his colleague observes, many of the workers from this “sweatshop” end up as patients in this ward. Reviewer James Scott thought that this choice of “mind-destroying monotony” was a “shrewd swipe” by Minton at “our crazy system of job valuation and payment”.19

However, Welbeck’s disquiet is also motivated by a pressing ethical issue that relates to the play’s social analysis. Patients wait for their turn to see the doctor, wondering whether he will suggest that they be released or whether he will recommend ECT (electroconvulsive therapy). When patients ask Welbeck for advice, he professionally defers to the doctor’s expertise – however, in private he expresses his doubts: he fears that their methods merely leave patients “dependent on artificially-induced epileptic fits”, knowing that they will inevitably need more of the same, whether in six months or two years. Welbeck wonders whether a crowbar to the head would have comparable results, but notes that the system would not countenance this because its damage would be visible. He says: “I have never seen a really disturbed person ‘normalised’, whatever that means […] we know nothing but the short-term effect of chemicals on the brain – we can only subdue, shovel pills in by the ton”. His colleague contests this, arguing that the profession uses the knowledge that they do have “in all good faith”, but Welbeck’s analysis would seem to be supported by the programme makers: Clarke told Naipaul that “Our knowledge of mental illness is very limited. We’re like Christopher Columbus at the beginning of his voyage. We’ve only just started to cross an unexplored ocean…”20 The results of this treatment – indeed, the results of various practices depicted during the play, even down to the loss of individual identity that Walter feels could be addressed if only he were allowed his own clothes – are recidivism and dependency. This supports the idea of the “womb” that was raised earlier in this essay or, to give a further meaning to the play’s title, a “farm” in which this dependence is grown. Naipaul summarises Minton’s position: “Every society hammers home its own particular definition of the normal and abnormal, subjecting its individual members to a barrage of propaganda.”21 Minton and Clarke put the play in its social context in comments in the Naipaul piece, which I’ve selected from here:

However, Welbeck’s disquiet is also motivated by a pressing ethical issue that relates to the play’s social analysis. Patients wait for their turn to see the doctor, wondering whether he will suggest that they be released or whether he will recommend ECT (electroconvulsive therapy). When patients ask Welbeck for advice, he professionally defers to the doctor’s expertise – however, in private he expresses his doubts: he fears that their methods merely leave patients “dependent on artificially-induced epileptic fits”, knowing that they will inevitably need more of the same, whether in six months or two years. Welbeck wonders whether a crowbar to the head would have comparable results, but notes that the system would not countenance this because its damage would be visible. He says: “I have never seen a really disturbed person ‘normalised’, whatever that means […] we know nothing but the short-term effect of chemicals on the brain – we can only subdue, shovel pills in by the ton”. His colleague contests this, arguing that the profession uses the knowledge that they do have “in all good faith”, but Welbeck’s analysis would seem to be supported by the programme makers: Clarke told Naipaul that “Our knowledge of mental illness is very limited. We’re like Christopher Columbus at the beginning of his voyage. We’ve only just started to cross an unexplored ocean…”20 The results of this treatment – indeed, the results of various practices depicted during the play, even down to the loss of individual identity that Walter feels could be addressed if only he were allowed his own clothes – are recidivism and dependency. This supports the idea of the “womb” that was raised earlier in this essay or, to give a further meaning to the play’s title, a “farm” in which this dependence is grown. Naipaul summarises Minton’s position: “Every society hammers home its own particular definition of the normal and abnormal, subjecting its individual members to a barrage of propaganda.”21 Minton and Clarke put the play in its social context in comments in the Naipaul piece, which I’ve selected from here:

Minton: Sanity is a problematical concept. Most of what passes for sanity out there just does not appeal to me. Walking around London is not much different from walking around a hospital. You see so many people visibly in distress […] Psychiatric therapy is fundamentally an agent for the state that exists as represented by the Church, marriage […] People are induced to accept rather than reject. Nobody is ever told to get the hell out of any situation that is causing him distress.

Clarke: It’s always “Go back! Go back!” People are never encouraged to go forward, to make a break…

Minton: Most people are encouraged to believe that they have responsibilities to all sorts of things. But one’s first responsibility is to oneself. The most important thing to know is what you don’t want to do.

Clarke: Go on! Sit down and have a depression! It’s nothing to be ashamed of. That depression is telling you something. It can be a very fundamental warning and emotional experience. We have got to get away from this guilt thing.22

Naipaul observes that Clarke and Minton “are an articulate duet”.23 Their comments also anticipate Archer’s thoughts on institutionalism in Scum, in particular his distinction between life inside Borstal (where “you act, you’re punished, you’re free”) and outside Borstal (where “you act, you’re punished by your own guilt complexes, and are never free”). My book on Clarke connects Scum with Stand by Your Screen, which “demonstrated the internalisation of the dominant ideology into the family unit, in line with Antonio Gramsci’s reading of consensus in his prison notebooks as ‘the “spontaneous” consent given by the great masses of the population to the general direction imposed on social life by the dominant fundamental group'”.24

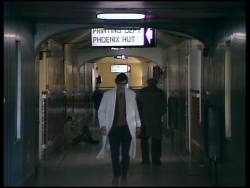

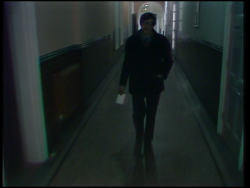

This “duet” includes the ways in which Clarke’s techniques reinforce Minton’s themes. Dennis Potter noted that “Funny Farm placed its damaged characters and underpaid male nurses in a shrinking world of endless passages, pale windows, distant scrabbles of voices, swishing doors and subterranean green colours.”25 Scott noted that these spaces were evoked by “some splendidly nightmarish camera shots of very long, narrow corridors, emphasising the inconvenience of the nineteenth century building and showing the incredible amount of sheer foot-slogging a nurse has to do in such a place”.26 Producer Mark Shivas suspected that “This was the start of Alan’s penchant for people walking down corridors” as Welbeck made “his lonely way about the building with the camera at his shoulder. This may have been assisted by the newer lightweight cameras, which made Alan a bit more flexible in getting about.”27 It is true that there are some walking shots that anticipate the signature device of Clarke’s 1980s work, in particular near the end, as the camera at speed accompanies Welbeck walking toward or away from the camera, pursued through bleak corridors of institutions like something out of Made in Britain or Elephant. Clarke develops this emergent motif, but that point should be qualified. The movement is not quite a hand-held camera perched at the character’s shoulder as in earlier Clarke pieces like The Hallelujah Handshake in 1970, or the Steadicam that would arrive to facilitate vibrant attachment to protagonists in his 80s work. The movement is nearer to a dolly, with a necessarily more distanced position. Also, these moving shots are quite sparse in Funny Farm. Usually, Welbeck’s walks are composed in static frames, or frames that are static as Welbeck approaches us, until he reaches a corner, when a pan follows him before the shot becomes static to observe the rest of his walk down another corridor. Static frames, in which characters move from background to foreground or vice versa (or, in the panning example just mentioned, both) are more characteristic of Clarke’s 1970s style, in particular in filmed pieces with the often-noted influence of Robert Bresson such as Diane.

This “duet” includes the ways in which Clarke’s techniques reinforce Minton’s themes. Dennis Potter noted that “Funny Farm placed its damaged characters and underpaid male nurses in a shrinking world of endless passages, pale windows, distant scrabbles of voices, swishing doors and subterranean green colours.”25 Scott noted that these spaces were evoked by “some splendidly nightmarish camera shots of very long, narrow corridors, emphasising the inconvenience of the nineteenth century building and showing the incredible amount of sheer foot-slogging a nurse has to do in such a place”.26 Producer Mark Shivas suspected that “This was the start of Alan’s penchant for people walking down corridors” as Welbeck made “his lonely way about the building with the camera at his shoulder. This may have been assisted by the newer lightweight cameras, which made Alan a bit more flexible in getting about.”27 It is true that there are some walking shots that anticipate the signature device of Clarke’s 1980s work, in particular near the end, as the camera at speed accompanies Welbeck walking toward or away from the camera, pursued through bleak corridors of institutions like something out of Made in Britain or Elephant. Clarke develops this emergent motif, but that point should be qualified. The movement is not quite a hand-held camera perched at the character’s shoulder as in earlier Clarke pieces like The Hallelujah Handshake in 1970, or the Steadicam that would arrive to facilitate vibrant attachment to protagonists in his 80s work. The movement is nearer to a dolly, with a necessarily more distanced position. Also, these moving shots are quite sparse in Funny Farm. Usually, Welbeck’s walks are composed in static frames, or frames that are static as Welbeck approaches us, until he reaches a corner, when a pan follows him before the shot becomes static to observe the rest of his walk down another corridor. Static frames, in which characters move from background to foreground or vice versa (or, in the panning example just mentioned, both) are more characteristic of Clarke’s 1970s style, in particular in filmed pieces with the often-noted influence of Robert Bresson such as Diane.

Funny Farm was shot entirely on video, at a time when the potential for Outside Broadcast for drama was becoming more widely accepted, although its merits were the subject of debate. Programme makers debated its financial benefits (increasing the amount of material that could be shot in one day, assuming a multi-camera set-up facilitated by a Lightweight Manual Control Room), and aesthetic strengths (matching the grain of studio interiors in order to reduce the jolt between location film and studio video) or weaknesses (Stephen Poliakoff spoke for many in seeing OB as “a real danger to drama”, a “poor relation to film” that resulted in a loss of “atmosphere and depth”).28 Indeed, Margaret Matheson, promoting the series of Play for Today that included Scum, stated that electronic cameras were not yet good enough for location shooting.29

Clarke moulded his signatures to location video. As in his Play of the Month production of The Love-Girl and the Innocent or his production of Minton’s Fast Hands for Plays for Britain, the static frames of Funny Farm sometimes constrain characters even when the shot size leaves them freedom to walk: like Lyuba in a key scene from The Love-Girl and the Innocent, Welbeck’s long walk at the end can only be stopped by going through a door and resolving a difficult decision. Funny Farm lacks the experimentation with lenses that distinguishes The Love-Girl and the Innocent, but builds upon A Follower for Emily, with which it shares framing strategies, sparse but expressive mise-en-scène (including imprisoning characters in door or window frames, placing characters in inflexible lines or using highly formal side-on shots) and visual repetition in the service of the study of institutionalisation.30

The visual treatment of the play’s opening and closing scenes further reflects theme. These are the only moments in which we leave the hospital, but the style is no more liberated outside than inside. In both scenes, Alan leaves a building and bikes away, either from home to the hospital or from the hospital to his home (though we don’t see the end of the journey on the latter occasion). Their visual treatment is similar: at first the route to his destination was on the left of the building, and when he bikes away he moves from foreground to background along the road: the two shots resemble each other but the vertical strip of road also resembles the framing of corridors throughout the play. There is a characteristically Clarke-like repetition created by the similarity between the beginning and the ending, but it also hints at the wider social themes discussed by Clarke and Minton earlier in the essay, problematising the distinction between institution and society, insane and sane, inside and outside – the concern with “the deadly virtues of state-sponsored sanity” that Naipaul saw in their statements.31 The idea that the programme has covered issues that affect us all is underlined by other captions at the end of the programme – “Every 3 hours a baby is born that will require continuous specialised psychiatric care for the whole of its life”; “1 person in 9 will enter mental hospital for treatment”. Again, the Radio Times provided supporting information: “patients suffering from mental disorder’ occupy 47% of hospital beds, and ‘Every fifth family has an intimate connection with mental illness.”32 These captions play over the shot of Welbeck starting his journey, just as the title caption Funny Farm played over a shot of a “normal” street, not the hospital.

The visual treatment of the play’s opening and closing scenes further reflects theme. These are the only moments in which we leave the hospital, but the style is no more liberated outside than inside. In both scenes, Alan leaves a building and bikes away, either from home to the hospital or from the hospital to his home (though we don’t see the end of the journey on the latter occasion). Their visual treatment is similar: at first the route to his destination was on the left of the building, and when he bikes away he moves from foreground to background along the road: the two shots resemble each other but the vertical strip of road also resembles the framing of corridors throughout the play. There is a characteristically Clarke-like repetition created by the similarity between the beginning and the ending, but it also hints at the wider social themes discussed by Clarke and Minton earlier in the essay, problematising the distinction between institution and society, insane and sane, inside and outside – the concern with “the deadly virtues of state-sponsored sanity” that Naipaul saw in their statements.31 The idea that the programme has covered issues that affect us all is underlined by other captions at the end of the programme – “Every 3 hours a baby is born that will require continuous specialised psychiatric care for the whole of its life”; “1 person in 9 will enter mental hospital for treatment”. Again, the Radio Times provided supporting information: “patients suffering from mental disorder’ occupy 47% of hospital beds, and ‘Every fifth family has an intimate connection with mental illness.”32 These captions play over the shot of Welbeck starting his journey, just as the title caption Funny Farm played over a shot of a “normal” street, not the hospital.

If the style, themes and “articulate duet” of writer and director bring to mind Clarke and Minton’s previous and subsequent work, in particular the problems that they would face with Scum, then so do responses to Funny Farm. In both pieces, the play was drawn from wide research. Michael Jackley recalled that “Roy had done a lot of research for the script, then Alan did a bit himself by going and working in the hospital for a bit; he got his little white jacket on and did a few stints. I think Tim Preece did too”.33 Unlike the feedback that the BBC gathered in the politicised climate of the banning of Scum, the feedback that the Radio Times gathered saw Funny Farm praised for its accuracy. Barbara Rudgley, a Senior Nursing Officer and experienced psychiatric nurse, said that Funny Farm “could almost be used as a training film. It was so absolutely accurate”. She noted that “Psychiatric nursing has very few rewards. You rarely ever see anyone get better. Most of the time you’re dealing with very sad, very under-motivated people who just don’t like life. That’s depressing.”34 Dennis Powell, a Nursing Officer, noted that “Nurses like [Welbeck] are definitely exploited”, although he thought that English people were now less likely to want to enter the profession and noted that he started out wanting to “do something worthwhile” but perhaps lacked that “sense of vocation” now.35 Rudgley stated that “The question is whether we ought to give patients an asylum where they can be themselves or whether we ought to pressurise them to return to society.”36 Jackley’s response to the recording demonstrated that the play raised similar ideas: “We had real patients coming in and out on that shoot. Your blood turned to ice when you went in. Obviously, I don’t agree with care in the community now, because it plainly doesn’t work, but you could see the arguments for closing places like this – mile-long corridors.”37

If the style, themes and “articulate duet” of writer and director bring to mind Clarke and Minton’s previous and subsequent work, in particular the problems that they would face with Scum, then so do responses to Funny Farm. In both pieces, the play was drawn from wide research. Michael Jackley recalled that “Roy had done a lot of research for the script, then Alan did a bit himself by going and working in the hospital for a bit; he got his little white jacket on and did a few stints. I think Tim Preece did too”.33 Unlike the feedback that the BBC gathered in the politicised climate of the banning of Scum, the feedback that the Radio Times gathered saw Funny Farm praised for its accuracy. Barbara Rudgley, a Senior Nursing Officer and experienced psychiatric nurse, said that Funny Farm “could almost be used as a training film. It was so absolutely accurate”. She noted that “Psychiatric nursing has very few rewards. You rarely ever see anyone get better. Most of the time you’re dealing with very sad, very under-motivated people who just don’t like life. That’s depressing.”34 Dennis Powell, a Nursing Officer, noted that “Nurses like [Welbeck] are definitely exploited”, although he thought that English people were now less likely to want to enter the profession and noted that he started out wanting to “do something worthwhile” but perhaps lacked that “sense of vocation” now.35 Rudgley stated that “The question is whether we ought to give patients an asylum where they can be themselves or whether we ought to pressurise them to return to society.”36 Jackley’s response to the recording demonstrated that the play raised similar ideas: “We had real patients coming in and out on that shoot. Your blood turned to ice when you went in. Obviously, I don’t agree with care in the community now, because it plainly doesn’t work, but you could see the arguments for closing places like this – mile-long corridors.”37

However, for all the detailed research, Clarke was keen to stress that Funny Farm was not a documentary: “It’s a play. It was written as a play. Nor is it just about nursing. It’s about people.”38 He would respond even more robustly when the banned Scum was subject to debates on drama documentary’s supposed mangling of drama and documentary techniques: Scum, he said, “is a play, it’s not a documentary, there’s been such a lot of I think rubbish talked about what’s a drama, what’s a drama documentary”.39 For Scott, Funny Farm was “definitely a play, not a documentary” but still carried “far more conviction than many a ‘factual’ programme on the same subject.”40 Scott was also comfortable with its dramatic compression – “While not all mental hospitals are as bad as the one in the play, some are undeniably worse”41 – although the idea of a drama as compendium of researched incidents would be challenged by the BBC executives who withheld Scum. Minton and Clarke did have a spat with the BBC over Funny Farm, but whether it related to similar issues of interference depended on your point of view. Christopher Morahan, the then-Head of Plays, noted that “It was commissioned as a seventy-five-minute play and it came out at one hundred and five. For me this was like working on a newspaper – we were working in fictional journalism if you like – and if you write a thousand words when your editor asked for five hundred, he has to spike half the article. This was during the three-day week, and we had to be off the air by eleven o’ clock at night. There was no way it could be broadcast at that length.”42 He observed that Clarke, faced with having to cut the play, “got very angry and petitioned the plays department against me – stood at the gates of the BBC and handed out pamphlets. It got pretty rough, and people said I had been censorious.” Clarke asked to remove his credit but Morahan replied, “Don’t be so silly, it’s very good and it’s improved for being a bit shorter. It’s your work and you should sign it”.43 Internal correspondence reveals resistance from other areas of the BBC to the idea of Clarke or Minton removing their names, finding that request unreasonable in line with the overrun from the agreed programme length.44 Ultimately, the play had a ninety-minute timeslot – 9.25 to 10.55, followed by Midweek, the Weather and Regional News before the scheduled closedown of 11.30.45 Minton was paid a fee to reflect the fact that the play was 92 minutes and 50 seconds long, constituting 18 extra minutes.46 Interestingly, Dennis Potter’s review’s only real quibble with the play was that it was “Too long, with too many uninterrupted monologues”.47

Minton, meanwhile, had a few plays and series commissioned by the BBC but not used, in the period just before and after Funny Farm – I won’t dwell on this since unused scripts were quite normal for writers, but a few of them are worth raising in relation to Funny Farm. Minton was looking to revisit a quite different piece that touched on issues of psychiatric care, Horace, a 1972 play that Clarke directed and Shivas produced. 48 The series – titled in commissioning documents as Horace Lives! – was commissioned by David Rose (its separate episodes commissioned across late 1976 and early 1977) but quite heated correspondence arose and the series didn’t ultimately appear until April 1982, as Horace for Yorkshire TV.49 It’s also interesting that various pieces involved Shivas collaborating with Minton – an episode of The Edwardians that was ultimately rejected, and then the commissioning of Scum. Indeed, contrary to Sian Barber’s recent claim that Scum was commissioned in 1976,50 Scum was actually commissioned by Mark Shivas in a document dated 8 January 1975. (Indeed, Minton said in 1978 that “The BBC commissioned Scum in 1975″.51 ) It was delivered in April 1975 – documents indicate that it was intended as a BBC2 Playhouse, but there are precedents for transfer – but it didn’t happen in that form. Minton told Kelly that Shivas “turned it down – said it was too biased”.52 Shivas told Kelly that “I don’t remember why I turned down Scum. I don’t think I’d had enough of Roy Minton. Whether they’d had enough of Mark Shivas – it’s possible.”53 In 1978, Minton had said that the BBC “rejected the script because of overlong running time”,54 and this is corroborated by internal BBC paperwork.55 Scum was then commissioned by Margaret Matheson as a Play for Today – in effect, the paperwork states, a re-write of a first draft – and delivered and accepted, in September 1976. (Filmed over March and April 1977, the completed Scum would be withdrawn before its intended November 1977 transmission.) Clarke had worked with Shivas before on several pieces, and would do so again in the late 1980s (when Shivas, as Head of Drama, faced controversies over Elephant and The Firm). Obviously I aim to return to Scum some day with all the extra information that I either couldn’t find space for in the book or have discovered since.

If I’m dwelling on some of the behind-the-scenes incidents on the periphery of Funny Farm, it’s because of one last idea raised by the play. Actually, it’s an idea raised by Dennis Potter in his review: the play, he said, “was notably successful in catching the pace and moods of any institution for the unwell, such as a crowded ward, an army billet or the Television Centre at Wood Lane.” (The connection appeals to Potter after a spell in hospital, where, he records, an invitation to watch the television coincided with an episode of Churchill’s People, which he feared “would set my recovery back by several weeks”.) Earlier, I quoted Potter on the play’s “shrinking world of endless passages”, voices, doors and “subterranean colours” – clearly those details had another resonance, which he built upon: “The patients didn’t seem to watch much television, another disturbing similarity to the inmates whose doors open onto a long corridor that goes round and round the Television Centre and never quite makes it out into the real world. Except in plays as good as this.”56 Minton had already connected institutionalisation with television in the descriptions of television and the presence of “screens” in Stand by Your Screen, but Potter’s quotation tempted me, in my book, to read Scum’s three bloodied protagonists after a riot – dragged through the corridors of an institution – in relation to the pressures facing Clarke, Minton and Matheson over Scum. Soon, all would be facing questions about their futures in a beleaguered institution, and television’s ability or willingness to interrogate institutions (and state attitudes to the public sector) would be open to question.

If I’m dwelling on some of the behind-the-scenes incidents on the periphery of Funny Farm, it’s because of one last idea raised by the play. Actually, it’s an idea raised by Dennis Potter in his review: the play, he said, “was notably successful in catching the pace and moods of any institution for the unwell, such as a crowded ward, an army billet or the Television Centre at Wood Lane.” (The connection appeals to Potter after a spell in hospital, where, he records, an invitation to watch the television coincided with an episode of Churchill’s People, which he feared “would set my recovery back by several weeks”.) Earlier, I quoted Potter on the play’s “shrinking world of endless passages”, voices, doors and “subterranean colours” – clearly those details had another resonance, which he built upon: “The patients didn’t seem to watch much television, another disturbing similarity to the inmates whose doors open onto a long corridor that goes round and round the Television Centre and never quite makes it out into the real world. Except in plays as good as this.”56 Minton had already connected institutionalisation with television in the descriptions of television and the presence of “screens” in Stand by Your Screen, but Potter’s quotation tempted me, in my book, to read Scum’s three bloodied protagonists after a riot – dragged through the corridors of an institution – in relation to the pressures facing Clarke, Minton and Matheson over Scum. Soon, all would be facing questions about their futures in a beleaguered institution, and television’s ability or willingness to interrogate institutions (and state attitudes to the public sector) would be open to question.

Credits (sources: the programme, and the BBC’s Programme-as-Broadcast file)

“Telerecorded on 18.12.1974 – VTC/6HT/96540/ED/ED – from Napsbury Hospital, Shenley Lane, Napsbury”57

Alan Welbeck (Tim Preece), Bill Spence (Chris Sanders), Graham (Francis Mortimer), Jack (Gordon Christie), Sidney Charlton (Michael Bilton), Arthur Rothwell (Allan Surtees), Ted Spinner (Bernard Severn), Jeff West (John Locke), Les Dewhurst (Anthony Langdon), Mr. Chadd (Wally Thomas), Jonathan (Kenneth Scott), Mr. Scully (Donald Bisset), Miss Taylor (Patricia Moore), Joyce (Helena McCarthy), Walter (Terence Davies), John (Michael Percival), James Ball (Arnold Diamond), Edna Ball (Dorothy Frere), Elsie (Gillian Wray), Baby (Ben Preece), Child (Joel Edwards), Patients (John Cross, Vic Hooper, John Dolan), Extras/Walk-ons (Floralyn Wardell, Sharon Sande, Paul Howlett, Julian Hudson, Eileen Brady, Donald Hoath, Ernest Jennings, Stanley Jacomb, Andre Ducane, Peter Kodak, Kelvin Sue-a-quan, Elaine Banham, Jacky Blackmore, Simon Ricco, Donat Joseph, Hal Collins, George Lowdell, Richard Hurgon, George Richardson, John Tucker, Alec Morton, Roy Seeley, Bill McNichol, Edmund Bailey, Andy Devine, Nancy Gabriel).

Costumes: Dorinda Rea; Make-up: Judy Neame; Lighting: Harry Thomas; Sound: Chris Holcombe; V.T. Editor: Howard Dell; Written by: Roy Minton; Script Editor: Richard Broke; Designer: Richard Henry; Producer: Mark Shivas; Directed by: Alan Clarke.

Since this piece was written, Funny Farm has been released by the BFI in their excellent 2016 Alan Clarke collection.

Originally posted: 31 March 2013.

Updates:

1 April 2013: added images; added credits; minor edits to footnotes and text.

19 April 2016: replaced 2013 images with non-timecoded images.

5 February 2017: added update regarding BFI release.

Pingback: ALAN CLARKE: PLAY FOR TODAY BIOGRAPHY | British Television Drama

Pingback: Beyond the reach of the cartographer: Dennis Potter the reviewing writer and writing reviewer | British Television Drama