by DAVID ROLINSON

Alan Clarke was neglected for a long time by television scholars and, because all but three of his approximately sixteen screen credits between 1967 and 1989 were for television, film scholars. This has changed in recent years: see Richard Kelly’s 1998 book of interviews1 and my book from 2005, the first (and, I hope, not last) critical study of Clarke’s work.2 Best of all, in May 2016, the vast majority of Clarke’s surviving work will be made available – much of it for the first time and some of it after previously being thought lost – in the BFI DVD and blu ray releases Dissent & Disruption: Alan Clarke at the BBC. Now everyone can find out what people have been so excited about. However, Clarke was first and foremost a television director, and as wonderful as it is that film fans are discovering Clarke, his work must be seen in the context of British television drama rather than as an aberration from it. Discussions of Clarke understandably prioritise his mid-to-late 1980s work, but this particular biography is designed to accompany the essays on this site about the dozen productions he made for Play for Today, which form around one-fifth of his total output.

Elsewhere, I raised the argument that the television play could form a kind of ‘studio system’ in which directors could develop: few directors grasped this opportunity as powerfully as did Clarke,3 whose Play for Today work epitomises W. Stephen Gilbert’s description – in an obituary after Clarke’s untimely death from cancer at the age of 54 – as ‘an unswerving champion of the individual voice and the noncomformist vision’.4 These pieces give a hearing to the ‘individual voice’ of characters (often unsympathetic characters): underdogs, the institutionalised (A Life is For Ever, A Follower for Emily, Funny Farm, Scum) and the brutalised (Nina, Psy-Warriors). He became, in the phrase of David Hare, a ‘driven filmmaker’, motivated to speak ‘on behalf of people whom he feels are getting a raw deal [and] by a passion to express what he doesn’t see expressed anywhere else in the culture’.5

Like several other key writers and directors from this period, Clarke came from a working-class background. The BFI’s database records his birthplace as Seacombe.6) He passed his Eleven Plus to go to grammar school. Taking an unorthodox route into television, Clarke emigrated to Canada in 1957 (after National Service), and, according to the Questors Theatre’s newsletter Questopics, had a ‘masterfully improvised’ career: ‘furniture remover, income tax assessor, miner, railway brakesman and chain-ganger, baker’s assistant, dance M.C. and a disc jockey at a skating rink’.7

Between 1958 and 1961 he studied Radio and Television Arts at the Ryerson Institute of Technology in Toronto, a pioneering course which gave him ‘training in broadcast methods’, including opportunities to make ‘closed-circuit productions of which several are taped and kinescoped during the year for further telecasting by co-operating private television stations’.8

Returning to Britain after graduation, Clarke worked as an Assistant Floor Manager at ATV and later Associated Rediffusion, on productions including Ready Steady Go. Between 1962 and 1966 he also directed various plays at the Questors Theatre in Ealing, and a touring production of James Saunders’s Neighbours in Paris and Berlin. In my book I quote a ‘facetious’ article that Clarke wrote for the Questors newsletter in response to speculation about his ‘striking’ and ‘original’ forthcoming production of Macbeth.

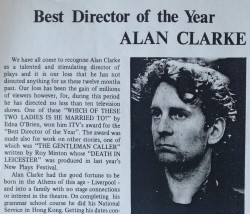

At last gaining entry onto a director’s course, Clarke served an apprenticeship directing Epilogues. At ITV between 1967 and 1969 Clarke directed plays for the strands Half Hour Story (1967-68), Company of Five (1968) and Saturday Night Theatre (1969-71), and episodes of series: the Ian Hendry vehicle The Informer (1966-67), the hugely acclaimed serial A Man Of Our Times (1968) and the massively publicised hit The Gold Robbers (1969). His early work, particularly his plays with Alun Owen, were distinctive: ITV awarded him Director of the Year for 1967.9 I’ve been delighted to return to his early work for Rediffusion for my own contributions to the Dissent & Disruption release, some of them until recently thought lost (The Gentleman Caller, The Fifty-Seventh Saturday, Thief plus, for my own interest, half of George’s Room) and for pieces to come on this site.

More biographically-based critics than myself have drawn correlations between the director and his productions. Like some of his protagonists, Clarke was an individual who collided with institutions: for the dissident Yuri in Nina, welcomed into a different class group in which his causes are empathised with but patronised, read Clarke the director and defender of threatened cuts to Funny Farm or the banning of Scum; for Trevor in Made in Britain hurling a paving stone through a Job Centre window, read Clarke, sometimes with writer Roy Minton, trashing restaurants or being arrested barely hours into arriving on location in Halifax. (see Richard Kelly’s book for these and other stories).10 I’m less interested in those sorts of connections, although the sense of commitment is an element that his friends and collaborators have drawn attention to: he has often been described as ‘his own man’, a phrase reminiscent of Roy Minton’s description of the lead character of Scum: ‘Carlin is his own man, not one of the shadows of this world. You meet him and you remember him’.11

Realist innovations are often associated with the extension of representation to previously neglected social groups, and, according to Stephen Frears, Clarke was attracted to the medium because ‘one of the things that television told was the history of ordinary working-class people in England’.12 Such concerns made Clarke synonymous with a tough, sparse observational style, and the visceral social realism and unyielding concern with institutional life that drove Scum. However, there is more to Clarke than this. His work was strikingly varied. He brought a masterful surety of tone to the colossal, mythic Penda’s Fen and to the intimate emotion of Diane and Nina, which are just two examples of a strand of female-centred, female-titled and (in the case of Nina and others) female-authored. He also excelled with the disorienting studio conceptualising of Psy-Warriors and Stars of the Roller State Disco and his rigorous stagings of Alexander Solzhenitsyn’s The Love-Girl and the Innocent, Georg Büchner’s Danton’s Death and Bertolt Brecht’s Baal. Belying his reputation for mischief is the professionalism required to build such a vast output – David Hare speaks for many of Clarke’s collaborators in saying that ‘Underneath Alan’s apparently casual manner – often late, often saying he didn’t know what he was doing, scruffy, apparently undisciplined – hours and hours of thought had gone in, mostly at night, where he’d been working on the script in bed at three o’ clock in the morning’.13

He has been praised and cited as a major influence by various filmmakers. These include people who worked with him (such as Danny Boyle, Tim Roth and Gary Oldman), people who met him (Paul Greengrass), and people who simply admired his films (such as Bill Hader in 2015 and Shane Meadows, especially in This is England (2007) and its television sequels,14 or Harmony Korine, whose namedropping prompted one critic to call Clarke the ‘father of NYC cool’).15 However, notwithstanding the occasional welcome comment such as Gavin Millar’s brief observation in 1983 that Clarke is ‘one of the best British directors around’,16 in the wider film culture his work was ignored for too long – the film magazine Cahiers du Cinema seemed to discover a new talent after Clarke’s Elephant(1989) was cited by Gus Van Sant as an influence on his own Elephant (2003).17 BAFTA’s greatest honour to his work came posthumously, naming their Outstanding Creative Contribution to Television award after him. Some critics made polemical and perceptive claims for his greatness: David Thomson in his Biographical Dictionary of Film (in which some sacred cows of Hollywood and British cinema fare less well),18 and Richard Kelly’s invaluable passion, compiling a book of interviews and overseeing a two-month retrospective at the National Film Theatre in 2002, the point of both being to argue for Clarke as ‘the most important British film-maker to have emerged in the last thirty years’.19 Like Ken Loach, during Clarke’s lifetime he was more appreciated abroad, winning international television prizes.

One explanation for Clarke’s relative neglect by critics during his lifetime may be the perceived ephemerality of the television play. None of his television plays have been repeated on terrestrial television since 1991, and although all three of his cinema films (the Scum remake (1979), Billy the Kid and the Green Baize Vampire (1986) and Rita, Sue and Bob Too (1987)) have been released on DVD, releases of his television plays have been more haphazard, until the Blue Underground Alan Clarke Collection and, in 2016, Dissent & Disruption. More work has been released in recent years: Fast Hands within Plays for Britain, Horatio Bottomley within The Edwardians, and his episode of The Gold Robbers within the release of that series. It’s wonderful to see cinema screenings of his work – the most complete season to date is running at BFI Southbank in March and April 2016 – but until the Dissent & Disruption set it seemed to conflict with Clarke’s engagement with audiences that we could only view some of his work in film archives or at cinema screenings: as David Thomson wrote of the NFT season in 2002, ‘if only the season was playing where it ought to be, and where it is most needed – on the television screen’.20 Film critics and academics (with notable exceptions like Julian Petley and John Hill) neglected television work with generalisations about it being ‘uncinematic’ (though this did not extend to European directors who worked for television, like Bernardo Bertolucci on The Spider’s Stratagem (1970)) though Clarke, like Dennis Potter, may not have enjoyed the anti-television rhetoric of much current writing on television’s ‘cinematic’ qualities.

Even critics comfortable with television have found it hard to focus discussions of television dramas around their directors. Howard Schuman has summarised the reasons for this:

In the context of British television, the title ‘director’ invokes deeply ingrained prejudices. Auteurist critical approaches to the golden age of television drama… usually focus on the writer, because television prided itself on being a writers’ medium. Directors were often regarded as little more than opinionated camera-movers.21

I discuss academic debates on television directors as authors – the prioritisation of writers, the ‘uncinematic’ aesthetic debate and so on – in my book.22 As of October 2015, there are twelve books in Manchester University Press’s ‘Television Series’ of monographs about television authors, but most are about writers and only one (my 2005 book on Clarke) on a director. However, even if his Play for Today work often demonstrates a director ‘serving’ the script, there is more to those plays than this indicates. If Penda’s Fen is distinctively David Rudkin’s vision, Rudkin has spoken highly of Clarke’s treatment of it.23 Even when Clarke had work allocated to him by television’s ‘studio system’, it helped him to develop according to David Thomson, who said Clarke was lucky ‘to be a director in a writers’ medium. Every film school in the world would benefit from seeing how a directorial personality can be sharpened and matured by keeping company with adventurous producers and good writing’. Clarke learnt ‘to acquire versatility with the camera and sure speed with the actors’, and when his ‘own style and preoccupations’ emerged, ‘they were all the stronger in their solid grounding’.24 Emerge they did. As Simon Hattenstone argues, ‘Although Clarke hardly ever wrote his own films, he was an auteur. He cajoled and teased every nuance out of the scripts, and the finished work always seemed to belong more to him than the writer’.25 Many others would agree, including producer Mark Shivas, who felt that Clarke’s work had ‘an unmistakable individuality and authenticity’ which made him ‘a real auteur in a way that very few British directors are’.26

This is a sound description of Clarke’s later work in the 1980s, a brilliant sequence of filmed dramas which dissect Thatcher’s Britain, shot through with formal innovation and his distinctively personal use of Steadicam: Made in Britain (1983), Christine (1987) and Road (1987), the Northern Ireland pieces Contact (1985) and Elephant, and his final broadcast drama, The Firm (1989). His Play for Today work, even when recorded on multi-camera video and Outside Broadcast (which are less respected by critics) is not merely a foreshadowing of his later auteur period; indeed, the studio Psy-Warriors (1981) is one of his most distinctive pieces.

The balance between the voice and the vision, or, as Mark Shivas puts it, ‘individuality and authenticity’, epitomises his Play for Today work. ‘Authenticity’ sums up the near-to-the-knuckle performances, the researched journalistic drive behind his more overtly crusading pieces, a concern for the everyday realities of previously-undocumented lives, and a complex realist style which can balance observation of and a strident invitation to participate with his characters. The thematic concerns of these plays include authority and the inner space of individuals, institutionalisation, and incarceration in both literal and figurative terms. Promoting Beloved Enemy (1981), Clarke identified his interest in ‘boxes – people being somewhere they don’t want to be, or wanting to be somewhere they can’t get into’.27 It’s appropriate that he should choose the imagery of a box, as arguably only Dennis Potter can rival his dedication to the box – television. Clarke exploited the freedom television drama (during this period of experimentation and institutional confidence) gave him in contrast to commercial cinema. Television mattered, and as a result Clarke leaves behind a tremendous body of work. Danny Boyle, director of Trainspotting (1996), 28 Days Later (2002) and Slumdog Millionaire (2008), described Clarke as ‘one of the most gifted, innovative and radical British film-makers’, who ‘transcended the boundaries of his profession’,28 and Paul Greengrass, director of Bloody Sunday (2002), United 93 (2006) and two Bourne films to date, has eulogised ‘unquestionably the finest body of work created by a British director’.29 Virtually all of it was made for, and facilitated by, British television, and his Play for Today productions are an esoteric, spiky and impressive part of that work.

Originally posted: 6 September 2003 on the old Mausoleum Club version of this site.

Updates:

2006: transferred to the old University of Hull version of this site.

2009: transferred to new Play for Today mini-site initially separate from the British Television Drama site

4 November 2010: transferred to main Play for Today site, with different URL

16 January 2014: added Millar quotation.

25 February 2014: very slight alteration to include link to February 2014 Psy-Warriors screening notes.

27 October 2015: rewrote some sections, moved some points to endnotes and deleted others, updated DVD release information, added Hader link and Meadows source.

16 March 2016: added college and theatre pictures from my own collection, cropped to respect their sources; rewrote introduction to mention 2016 releases; added mentions of the release and season elsewhere; added brief qualification to point about the ‘cinematic’; minor typographical revisions throughout.

31 March 2016: added one sentence to first paragraph to rework it and moved tribute quotations from first to final paragraph; replaced a few individual words throughout in order to reduce repetition (e.g. ‘dramas’) or clarify meaning of material added earlier in March.

4 March 2017: standardised presentation of ‘Updates’ legacy information (2003, 2006, 2009, 2010) in line with current site practice; removed ‘(first published: 2003)’ from byline as a result.

Richard Kelly (editor), Alan Clarke (London: Faber, 1998 ↩

Dave Rolinson, Alan Clarke (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2005). ↩

Dave Rolinson, ‘The Last Studio System: A Case For British Television Films’, in Paul Newland (editor), Don’t Look Now: British Cinema of the 1970s (Bristol: Intellect, 2010), pp. 164-176. See also the Introductory essay on Play for Today on this site. ↩

W. Stephen Gilbert, ‘Alan Clarke’ obituary, Guardian, 26 July 1990, p. 13. David Hare recalls Clarke making an analogy between 1930s and 40s Hollywood and the BBC as a place in which a director could do ‘a lot of different work’ – Kelly, Alan Clarke, p. 67. ↩

Alan Clarke – ‘His Own Man’. ↩

This corrects a statement I made in the 2003 version of this essay. For the BFI database, see http://www.bfi.org.uk/filmtvinfo/ftvdb/. ↩

Anonymous (presumably Alfred Emmet), ‘Best Director of the Year Alan Clarke’, Questopics, February. Many thanks to Questors archivist Carla Field for this and other pieces on Clarke’s theatre work. ↩

Many thanks to John E Twomey, Professor Emeritus at Ryerson, for programmes of study and other helpful archive material from the Ryerson Institute of Technology. ↩

Rolinson, Alan Clarke. ↩

Kelly, Alan Clarke. ↩

Roy Minton, Scum (London: Arrow Books, 1979), p. 14. (Page reference from 1982 edition.) ↩

Alan Clarke – ‘His Own Man’ ↩

Ibid. ↩

See David Rolinson and Faye Woods, ‘Is This England ’86 and ’88? Memory, haunting and return through television seriality’, in Martin Fradley, Sarah Godfrey and Melanie Williams (editors), Shane Meadows: Critical Essays (Edinburgh University Press). ↩

Mark Venner, ‘‘I’m the Daddy now! Or how great British realist Alan Clarke can be father of NYC cool’ in Film Ireland, Number 83, October/November 2001, pp. 20-23. ↩

Gavin Millar, ‘British images’, The Listener, 2 June 1983, p. 37. But Millar is discussing the cinema version of Scum, broadcast on Channel Four that week. ↩

Jean-Philippe Tessé, ‘De l’origine d’une espèce’, Cahiers du cinema, October 2003, 15. ↩

‘Alan Clarke’, Biographical Dictionary of Film, London, André Deutsch, 1995 edition, pp. 131-133. ↩

Kelly, Alan Clarke, p. xxi. Mark Shivas bemoaned the lack of acknowledgement during Clarke’s lifetime, remembering that he told Clarke that ‘had he been called Clarkovsky rather than plain old Alan Clarke, he would have had an international reputation’ – Ibid, pp. 225-226. ↩

David Thomson, ‘They don’t make ‘em like him anymore’, Independent on Sunday, Arts Etc, 2 March 2002. See also ‘Walkers in the world: Alan Clarke’, Film Comment, 29:3, May-June 1993, pp. 78-83. Other Clarke retrospectives include Edinburgh in 1998 and London’s Riverside in 2005. ↩

Howard Schuman, ‘Alan Clarke: in it for life’, Sight and Sound, 8:9, September 1998, p. 18. ↩

See Rolinson, Alan Clarke. I tackle the subject more broadly in Don’t Look Now. ↩

For instance, when I conducted a Q&A with David Rudkin on stage after a screening of Penda’s Fen at Manchester Cornerhouse in October 2006. ↩

Thomson, ‘They don’t make ’em like him any more’. ↩

Simon Hattenstone, ‘Hitting where it hurt’, Guardian, ‘Review’ section, 1 August 1998, p. 4. ↩

Mark Shivas, postscript to David Hare, ‘A camera for the people’, Guardian, 27 July 1990, 35. ↩

Benedict Nightingale, ‘Nasty business’, Radio Times, 7-13 February 1981, p. 15. ↩

Alan Clarke – His Own Man’,documentary made by 400 Blows Productions, tx Film Four, 18 September 2000. ↩

Paul Greengrass, ‘My Hero: Alan Clarke’, Guardian, G2, 1 February 2002, p. 8. ↩

Pingback: Stella (1968)

Pingback: Alan Clarke - Wikipedia - SAPERELIBERO

Pingback: Funny Farm (1975) | British Television Drama