by DAVID ROLINSON

Dennis Potter’s non-fiction writing is a tremendous body of work – reviews, radio talks and newspaper features on television, radio, books, society, politics and more.1 I was going to just run through some of his television reviews, but Potter wouldn’t let me get off that lightly. His non-fiction work interweaves with his fiction work in characteristically multi-layered, provocative and entertaining ways. He never lets us forget that words matter. So the word “reviewing” becomes unreliable, which is annoying if you’ve put it in your title. He’s not just a writer who wrote some reviews – his writing reviews, and re-views, his own plays and much more besides. There are lots of traps to fall into, as we can tell from the start of Follow the Yellow Brick Road…

[Extract: 1:38 to 4.25]

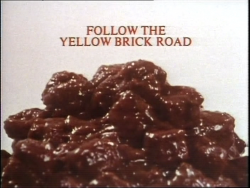

Jack Black sits and comments on drama, including its content and style – it’s tempting to use Jack to introduce Potter the TV reviewer, sitting in Ross arguing with London drama,2 though I’d have to have my tongue in my cheek since Jack uses a string of clichés: wondering when something’s going to happen before viewers “switch over or switch off”; later he says these are dirty, sex-obsessed plays by people who go to Trotskyite parties and sleep around. As always, although there are biographical resonances to this,3 Potter is playing with seeming autobiography and his own previous work: Jack’s visit to a psychiatrist resembles scenes from Moonlight on the Highway and Hide and Seek;4 as does Jack’s trauma about looking for God and finding nothing but “Filth” and “slime”, though Potter in the published play says “I am afraid to concede that the excess of disgust jerking out from Jack Black’s mouth more closely represented what I felt about the cold and faithless world, and its suffocating materiality, or my cold and faithless self”. Jack says “I don’t want to be in this play”.5 His comments about bad dialogue remind us of Hide and Seek and the later Karaoke – the need to write your own lines in life – and our place under an Author-hyphen-God that John Cook traced throughout Potter’s work (one of Jack’s first lines here is “God Almighty”). Whether Jack’s being watched by God or the naturalistic gaze of the cameras, how can he create or re-create himself, we wonder as we see him view and re-view the adverts for Krispy Krunch and Waggy-Tail Din-Din in his subjective memory?

So how can he create his reality? Previewing Blue Remembered Hills in 1979, Potter said: “The most beautiful part of being alive is our capacity to shape our lives by language, by stories. The world is full of the murmur of human beings trying to reshape reality.”6 Writing, rewriting and revision are vital to The Singing Detective. John Caughie observed the importance of “writing and reading”, as Philip Marlow “tries and fails to use art to sublimate pain and order a disordered reality”.7 Rewriting his fictional stories in his head,8 Marlow is also rewriting himself, as Antony Hilfer observes: “the distinction between replaying and revising becomes crucial, as story-revision becomes self-revision”.9

Potter, too, is rewriting earlier stories: The Singing Detective uses bits of Stand Up Nigel Barton, Emergency Ward 9, the unpublished Country Boy10 and non-fiction including Between Two Rivers, The Glittering Coffin and newspaper columns, plus Hide and Seek (of course, when Gibbon tries to psychoanalyse Marlow by reading a sticky bit of Marlow’s book, the words are from Potter’s novel Hide and Seek). The Singing Detective and Stand Up Nigel Barton are linked by classroom scenes in which a boy is wrongly blamed for the lead character’s childhood crime of either stealing a daffodil or shitting on a desk.11 But between these two pieces came ‘Telling Stories’, a Potter article for New Society in 1975. In a talk about the Forest of Dean, Potter mentioned the real-life incident that inspired the scene, and found out what happened to the real boy. How do we use this? It would be tricky to use it as autobiographical “proof” –12 Potter uses the codes of autobiography as a dramatic tool; as he said, “When the novelist says ‘I’ you know he doesn’t mean ‘I’, and yet you want him to mean ‘I’.”13 ‘Telling Stories’ is a fascinating article in its own right about what Potter calls “the relationship between fiction and lying”.14 Potter doesn’t say whether the boy’s fate is true or a lie because “it’s a truth either way”.15 Over the years, in reviews, journalism and interviews, Potter not only worked through key themes but also made his persona an intertext, just as he said that he survived his illness through the power of “the contest between my real self and my invented self”.16

In The Singing Detective we find “an essentially subjective capacity, a cinema of the mind, by which the subject replays scenes of his subjective formation and past”.17 Except, this is John Bowen’s description of David Copperfield.

There’s no room here to develop a full comparison between Potter and Charles Dickens.18 However, one quick point can help to explain the idea of Potter as a “reviewing writer”. Several gestures are repeated in The Singing Detective, including characters waving,19 which we see as originating from young Philip’s departure on the train. We see it partly from Philip’s perspective, moving away from his father. Similarly in David Copperfield, the moment in which David’s mother held up her baby while he left in the carrier’s cart – “I was in the carrier’s cart when I heard her calling to me. I looked out, and she stood at the garden-gate alone, holding her baby up in her arms for me to see. […] So I lost her.” – is subject to repetition: Dickens repeats the phrase “holding up” during the description and David remembers the moment. The sense of loss, and of moving away from childhood, is underlined in this 1999 TV version, in which we take David’s point of view and move away. These two stories have obvious things in common, each featuring a writer looking back, with a sense of author-character and author playing with modes of autobiography, but there are similarities that could be explored further.20 For now, sticking to my central idea, Bowen describes moments across Dickens’ work “when a character is able to witness, with hallucinatory clarity, a scene from his or her past, and yet is unable to participate in it or change anything” – and that shares a dynamic with Potter. As Potter put it in Hide and Seek: “hypnogogic images, the strangely potent montages which come at a mind already lapsed into a sort of sleep.”21 But Marlow, like Potter, can review as well as re-view. So Potter’s a reviewing writer,22 but he’s also…

…a writing reviewer. What do we do with Potter’s reviews? In his article ‘Dennis’s Other Hat’, Philip Purser said “It is only natural to wonder to what extent this critical function informed his creative process and vice versa. How many of the familiar obsessions of the plays can be first discerned in the reviews? Does he draw on his experience of writing for television to write about television?”23 Purser gives insights into the job of TV reviewing, and his questions here help dig into themes in the plays and Potter’s views on issues such as the use of studio, debates on non-naturalistic form, changes in television practices and policies (which could be developed), and attempts at autobiography. But Potter’s non-fiction needs more attention as non-fiction. We could see this work as an example of current concepts in Television Studies, as “transmedia” texts or as “paratexts” (material circulating around a text, like continuity announcements and trailers). The challenge is to see Potter’s non-fiction work in these areas as part of his body of work.24 Yes, it helps our analysis of The Singing Detective to know the ‘Telling Stories’ article which almost pops into the mouths of Marlow and Gibbon at a crucial moment, but it’s also part of the layers of quote-unquote-biography in its own right and as part of Potter’s construction of himself as publicly-known writer. Potter’s projection of self isn’t just publicity, it’s part of the impact of the fiction – the wanting “I” to be “I”.

Studies of Potter have barely scratched the surface of Potter’s non-fiction writing, using it in the sort of selective way that I’m about to do myself. I’ll just pick three television reviews that haven’t yet been explored in Potter studies. Giving a glowing review to the fabulous Penda’s Fen, written by David Rudkin and directed by Alan Clarke, Potter engaged with its themes, with a boy in ‘a patch of landscape and so of mindscape’: “The place where we grow up, where we learn to speak and then not to speak, is always beyond the reach of the cartographer and forever charged with the intensity of those first perceptions which turn words or songs heard in the head into particular configurations of local topography”.25 If we take Purser’s suggested methods then we might suspect that Penda’s Fen helped inform Blue Remembered Hills, were it not for the familiarity of the phrasing. In Hide and Seek the previous year, Potter had written, “No cartographer can trace on any known map the place where we were born and bred. Unlocatable is that lost land where we first hear someone calling our name. Gone is the place where we learn to speak and read and laugh and cry (or, worse, not cry), gone like trees walking.”26 Again, my point here isn’t to just note imagery and themes in Penda’s Fen that would be interesting to compare with Potter’s fiction and non-fiction,27 because it’s the dialogue between texts that interests me, whether you call it recycling, drawing correlations or re-viewing.

David Rudkin, John Hopkins and others remind us that Potter was not unique carving out an individual career and personal themes and styles in that television structure – but paradoxically, recognising this, and Potter’s interaction with them in reviews, helps us to see what is distinctively Potter. Yes, Potter’s engagement with developments in TV helps us study those developments, including the shift to more director-led drama and the phasing out of Play for Today, which – along with documentaries and late-night arts programmes – he said, with a lovely turn of phrase, were “the major area left on TV still capable of transmitting the nourishing zest of an individual imagination which necessarily cares not a controller’s fart for ratings charts or conveyor-belt packaging.”28 He had fun with the BBC, of course. He praised Roy Minton and Alan Clarke’s Funny Farm for “catching the pace and moods of any institution for the unwell, such as a crowded ward, an army billet or the Television Centre […] The patients didn’t seem to watch much television, another disturbing similarity to the inmates whose doors open onto a long corridor that goes round and round the Television Centre and never quite makes it out into the real world.”29

Purser brings out some interesting moments of Potter holding surprising, even contradictory, opinions in relation to what others are doing in TV. We could add others. Potter’s review of the last episode of Philip Martin’s Gangsters described the series as “so obnoxiously delighted with its own gaggle of second-hand styles that it seemed to be licking itself all over”.30 To be fair, his main problem is the racial violence in the series, but it’s a surprising dismissal of this episode, which writes out its lead character in a provocatively non-naturalistic way,31 and in which a character walks off-set, ending a crime series with a non-naturalistic device even more provocative than the ending of Follow the Yellow Brick Road, when the camera seems to confirm Jack’s fear that he’s in a television play. When Lindsay Anderson later showed the studio in The Old Crowd,32 he was criticised by reviewers whom he felt were not able to deal with his innovative approach,33 seemingly unaware of television’s many attempts at Brechtian experimentation: indeed, Julian Barnes criticised the “stale old device […] of including shots of the camera and the director’s gallery”.34 Anderson expected flak from television critics because they disparaged the medium even more than he did.35 But Potter was not that sort of critic.

As programme maker and critic Potter was of course involved in a debate, as John Cook noted, about “the choices between ‘naturalism’ and its alternatives”: “not simply a question of which dramatic style to use but between two fundamentally different ways of seeing.”36 Introducing the Follow the Yellow Brick Road script, Potter talked about “the quality of response.” Just as Jack Black talked about the timeslot of the play he’s in, Potter was interested in how programmes exist in schedules: “Bullets on one side and football on the other… the life of a play so doubly boxed can be sucked away in the surrounding flow. Worse, a panel game, a plastic-prairied Western, a hard-eyed news bulletin, Wimbledon, a detective melodrama and an original play eventually submerge together into the same kind of experience” in what he called a “landscape of indifference”.37 When Potter thought that The Singing Detective hospital scenes should be shot in the TV studio, he, like Ken Loach and Tony Garnett,38 saw how dramas could use their place in the schedule to invite reflection on how other forms (like news) work. Potter – like Gangsters, ironically – blended and confronted genres, from advertising to Westerns to soap.39 His reviews show an awareness of texts in the context of the everyday, in schedules, with the ephemera of broadcasting, and how people watch television.40

His reviews confront this idea of an indistinguishable flow, and like Follow the Yellow Brick Road hope that television drama and human experience aren’t packaged like tins of dog food.41 Like Russell T. Davies, who said the “T” stood for “television”, Potter was engaged with this popular medium that once made his “heart pound”. So, if we’re to be cartographers drawing maps through Potter’s work, we need to use much more of his non-fiction work. A published collection would be brilliant: important and entertaining, ranging from literary criticism and religious talks to Blake’s Seven, party political broadcasts, sport and Swap Shop, the latter prompting Potter to suggest swapping “Noel Edmonds for an equally hirsute gooseberry”,42 which shows us again that Potter’s work is often timeless. But the arrival of the Potter archive will be an important step.

This is the edited text of a talk at the Dennis Potter Day at Dean Heritage Centre, Forest of Dean, 29 June 2013.

Thanks to everyone at the Dean Heritage Centre on 29 June. Thanks also to Ian Greaves and John Williams.

Since this article was written, myself, Ian Greaves and John Williams have edited a collection of Dennis Potter’s non-fiction writing. Dennis Potter, The Art of Invective: Selected Non-Fiction 1953-1994 was published by Oberon Books in 2015.

Originally posted: 31 July 2013.

Updates:

5 February 2017: added link to The Art of Invective.

Pingback: Philip Martin (1938-2020) Part Three: Peter Ansorge on script editing Gangsters (BBC 1976-78), plus contributions from David Edgar and David Rudkin. – Forgotten Television Drama

Pingback: (Times and) Spaces of Television – Doctor Who: Warriors’ Gate (1981) – British Television Drama