by OLIVER WAKE

Studio 4 Adapted and translated by: Rudolph Cartier; From: Erwin Sylvanus (play); Director: Rudolph Cartier

Doctor Korczak and the Children is one of the most unusual and compelling television plays of the 1960s.1 Its subject is tragic and fascinating, while the production itself is interesting in its own right for a myriad of reasons. The extremity of its rejection of naturalistic television drama conventions is startling and it remains an almost unique surviving example of a period of such experimentation at the BBC at the beginning of 1960s. It also illustrates how the reach of a stage text can be expanded to whole new audiences with sympathetic translation into the new medium. This article aims to give an overview of this extraordinary production and its reception by its audience.

The play tells the tragic true story of Dr Janusz Korczak, who ran the Warsaw orphanage for Jewish children until August 1942, when the Nazis deported him and his nearly-200 orphans to the extermination camp at Treblinka, where they were murdered. It was originally written for the German theatre by Erwin Sylvanus in 1957 in reaction to what he perceived as the German people’s affected blamelessness for Nazi crimes. To suggest their silent complicity in these atrocities, Sylvanus wrote the play to be acted without sets or costumes, by actors playing themselves as if being drawn into the story, becoming part of it. This approach was akin to that used with great success by Italian dramatist Luigi Pirandello to gain his audience’s involvement. “Sylvanus’s play is one of the most brilliant demonstrations of the practical effectiveness of the Pirandellian method”, wrote George E Wellwarth in the 1968 anthology Postwar German Theatre, calling it an “extraordinarily bitter idea”.2 In the five years following its debut, the play was performed in 80 theatres across 14 countries and was televised in seven different languages.3

Doctor Korczak and the Children came to British television as the opening play in the second series of the BBC’s drama anthology Studio 4 (1962). Named after the studio in the BBC’s Television Centre that its plays were recorded in, then one of the most modern studios in the world, the series aimed to “tell a story in exciting visual terms”, and was a successor to the previous year’s Storyboard.4 Calling for no sets or costumes, Doctor Korczak and the Children was the sort of visually unusual work suited to Studio 4. The play was produced and directed by BBC staff producer Rudolph Cartier, who translated and adapted the German text himself for what was reportedly its first English language performance.5 It was the eighth television version of the play.6 Many years later, Cartier explained how budgetary constraints inspired him to produce the play without sets or costumes, but it seems he was misremembering, or perhaps embellishing the truth for the sake of a good story, as this innovation is exactly as per the stage text.7

With so few trappings, and being entirely confined to the studio, the play was unusual for Cartier, who specialised in ambitious large-scale productions and usually made good use of pre-filming. In recognition of this departure, this “starkly simple” play (along with another drama) was later referenced in Cartier’s annual review for 1962 as a pointer “to a valuable extension of his already wide range.”8 How Cartier came to direct Doctor Korczak and the Children is not known (no production file exists) but it seems likely that he chose it himself. Cartier, who was Austrian by birth but British by naturalisation, was well acquainted with the European stage, particularly German-language drama, and on a number of previous instances had suggested plays from these sources for his BBC productions, often following his periodic visits to continental Europe. We can also speculate that the play’s subject may have been of special personal interest to Cartier, as he had himself fled the Nazis in the 1930s and subsequently lost his parents in the Holocaust.

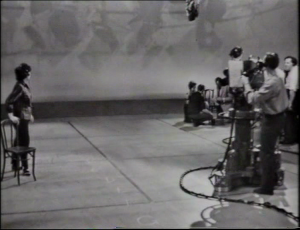

In an effective updating of the stage text for television, Cartier’s production opens in an empty studio with the crew in shot. Genuine production assistant Paddy Russell greets the actors (Anton Diffring, Joseph Furst, Albert Lieven, Petra Peters and Bruce Prochnik), who voice their concerns about the lack of a script. From there, the play unfolds as if in improvisation, each actor taking a character and exchanging it when necessary. They give voice not only to Korczak, his nurses and children, but also the streets of Warsaw and the orphanage itself. To avoid stereotyping the Nazi officer as a monster, on whom all blame could be placed, he is given a home life with a wife and son. This reinforces Syvanus’s contention that ordinary people were responsible for the horrors of the Holocaust.

Sylvanus’s address to his audience, which was originally intended to be German, could never have anything like the intended impact when played to British viewers. Not only did they not belong to the nations that perpetrated the Holocaust, but they could complacently reassure themselves that they were on the ‘right’ side in the conflict, having opposed the Nazis. Recognising this, Cartier updated the script to make it more relevant to a British audience, adding an introduction in which Albert Lieven as the narrator challenged the audience to engage with the play: “Don’t be afraid, you can always switch off, or over to the other channel. You are still not committed to what we are going to show you…” Cartier also adds a joke with the line: “Look at me, another Nazi”, delivered by Anton Diffring, who had become stereotyped in such roles in television and film. The surviving rehearsal script for the production was clearly prepared before most of the casting was complete so unsurprisingly lacks this particular line, which must have been a late addition once Diffring’s involvement was confirmed.9 Lieven is, however, named in this version of the script, indicating he was likely cast before the other actors.

This script also confirms that the play was in rehearsal away from BBC facilities, as was the norm at this time, between 18 and 30 June 1962, before moving into the television studio for final technical rehearsals on 1 and 2 July, with the play recorded on the evening of the second. The recording was scheduled between 8.30pm and 10pm, giving the actors and production crew only 90 minutes to capture the 62 minutes of the drama. Such tight recording schedules were the usual pattern for television drama in this period. Many programmes were still transmitted ‘live’ and those that had the benefit of pre-recording were recorded in a small number of ‘as live’ takes comprising several consecutive scenes, to minimise subsequent editing.

More unusually, Doctor Korczak and the Children was not recorded to videotape but to 35mm film, with the electronic studio output routed directly to the telerecording facility, which was more commonly used to create a film duplicate of a programme made on videotape, or to record from live transmission. This method was sometimes used in drama on productions that were more complicated than the norm, perhaps involving a lot of action, as the resulting film print could be edited with more ease than a videotape. However, in this case, the play is staged as simply and with as little action as any drama could be, making the use of primary film recording surprising. The reason may be more prosaic. Sometimes telerecording was used simply because the BBC’s video recorders were already fully engaged on other programmes recording at the same time. Although speculation only, it’s possible that telerecording was the standard method of recording Studio 4 plays as the strand’s attempts at visual innovations may have made the greater versatility of film desirable for many of its productions, if not actually necessary in the case of Doctor Korczak and the Children.

The excellent performances of the play’s small cast are an integral part of the drama’s success. Joseph Furst was the only member of the cast to take just one role (Korczak), and he is particularly notable. Furst’s performance becomes absolutely gripping as the play progresses, with Korczak coming to realise the fate that is in store for his orphanage and displaying the moral courage with which he elects to accompany the children under his care to their deaths. At the conclusion, Russell reappears to read the credits (except for the title of the play, there are no on-screen captions), and with each of the actors’ names, the camera lingers for a moment on an empty space, ending on the building blocks played with by Bruce Prochnick, who represented the orphanage’s children. This effectively conveys the suddenness and the silence of the disappearance of Korczak and his children, and by extension the similar fates of millions of others.

The BBC’s Audience Research Report estimated that the play performed badly in terms of its audience share against ITV, as might be expected given the unconventional and harrowing nature of the programme.10 Doctor Korczak and the Children won 7% of the potential audience against 23% for ITV, which screened a networked episode of the series Probation Officer (1959-62) during most of the same slot. The play’s Reaction Index of 55 was slightly ahead of the average of 53 for the previous series of Studio 4, but well below the average of 64 for all television plays across the first half of 1962.11

The report noted that some of the sample audience were upset by the play’s lack of scenery, costumes and props, and some found the play to be too long in “coming to the point”.12 Some of the sample disliked the theme of the play, feeling memories of the war should not be revived. This was a common complaint about dramas set around the Second World War, which was still painfully recent for many.13 Several of the viewers reported that they acted upon Lieven’s reminder that they were free to switch the programme off. Those who persevered were more enthusiastic, with the play being found “intensely gripping and moving”, with the unusual production style adding “a sense of stark reality”; “a box of bricks, chairs and our own imagination were more than enough”, stated one respondent. Indicating that Sylvanus’s unusual method had been as successful as could have been hoped for the British audience, one of the sample viewers reported: “The actors really seemed to be going through this ordeal themselves, and not just acting it”.

The professional critics of the British press were largely positive in their notices after the play’s sole transmission. In his Daily Herald review, Dennis Potter, not yet a television playwright himself, wrote that “This play was simple, truthful and unbearably moving”.14 In The Observer, Richard Hoggart reported that the play

worried me at the start: it seemed too mannered, even for a deliberately stylised production. But that soon passed and this terrible and marvellous story of the Warsaw ghetto came over with great force and authenticity. With no props, no costumes, no settings and a very bare script, this was a form of Brechtian “epic” theatre adapting itself to television with a great deal of success.15

Mary Crozier’s review in The Guardian was even more enthusiastic. “Few of the BBC’s “Studio 4” productions have been as compelling”, she noted, going on to explain that

The play was translated and produced by Rudolph Carter with a starkness and a strong grip that made one wish to see him more often at work on these lines with less elaborate material than usual. … The austerity of the means, the use of one child to represent all, the absence of properties so that the doctor arranged an imaginary prayer shawl on his shoulders as he said his last prayers, the snatch of distant singing of the unseen children as they entered the gas chamber, these and many more touches heightened the profound effect of the play.16

Another positive notice came from the Daily Mirror’s Clifford Davis, who praised the “simple and unusual approach”, finding the drama “Strange intense stuff – but compelling too.”17 He continued: “The story provided viewers with an hour of sorrow. I cannot recall when television has ever before reproduced such poignant anguish… As a condemnation of racial intolerance this “Studio 4” production was superb.” The Liverpool Echo and Evening Express thought the play “triumphant”, with a “compulsive” story and “impeccable” cast, although the critic found the “clever-clever” opening off-putting.18

A negative review came from The Stage and Television Today, which felt it had only been the horror that inspired the play which had stirred foreign audiences “and not so much the art of the dramatists, for try as the actors did, the words to move, with the exception of the epilogue, were not there.”19 The unnamed critic concluded:

The play suffered from the initial setback of a well tried theatrical gimmick from which it only recovered in flashes due to one or two short but brilliant pieces of acting. When you dispense with sets, costumes, and props, the suggested dramatic situation must be backed by powerful and poetic dialogue.

Agreeing with this criticism of the ‘gimmick’ was the critic of The Jewish Chronicle, who disliked the artifice of the start of the play and the periodic interruptions by the framing device. Despite this, they found it “one of the most compelling and moving plays seen on television for many years”.20 They reported how:

The whole overwhelming tragedy of the Jewish people was brought home starkly and powerfully. The ending, with the children singing songs as they go into the gas chambers, followed by the recitation from Ezekiel was almost unendurably moving… The acting lived up to the supreme importance of the theme. Joseph Furst, as Dr. Korczak, was dignified and a believable, if heroic, human being. Albert Lieven as the commentator and link in the action was a convincing and commanding figure.

The reviewer went on to note that “Rudolph Cartier, who has won fame with large-scale productions in traditional style, showed he can handle an ultra-modern play with a sure grasp.” They concluded on the enduring importance of the play’s theme: “It is to be hoped that it will be repeated—with perhaps cuts at the beginning. This play is the best answer to those who believe that freedom should be granted to preachers of race hatred.”

Doctor Korczak and the Children is one of only two Studio 4 productions for which recordings survive out of a total of 18 transmitted plays. No examples survive from Studio 4’s precursor, Storyboard, nor its successor Teletale (1963-64), which also aimed to innovate with visual storytelling. The other remaining Studio 4 play is The Victorian Chaise Longue (1962), from earlier in the series, which is less obviously experimental in its realisation.21 This dearth of recordings makes Doctor Korczak and the Children almost unique as an example of a trilogy of drama anthologies which experimented with the staging of television drama, breaking and testing the still-young conventions of the medium.

Doctor Korczak and the Children’s telerecording to 35mm film directly from the studio, as noted above, rather than being videotaped, may at least partially explain its survival; videotapes were regularly reused but, whilst they could still be disposed of, film prints had no similar recycling potential. Cartier went on to tackle anti-Semitism and the Holocaust in a number of other (albeit more conventional) documentary dramas for the BBC during the 1960s, notably The Burning Bush and The Joel Band Story.22 Doctor Korczak and the Children was seen again in 1990 when it was screened at the National Film Theatre in London as part of a retrospective on Cartier’s television career, and once more in 2012 as part of the British Film Institute’s ‘Beyond the Fourth Wall’ season of experimental television drama.

Doctor Korczak and the Children is a deeply affecting and compelling drama, telling a true story which deserves to be remembered. The story has been dramatised many times, for stage, radio, television and film, but this version is the most unusual. It demonstrates just what was achievable with minimal resources but unlimited resourcefulness on the part of its creators and a desire to produce something truly arresting. In those terms, Doctor Korczak and the Children was most certainly a great success.

© Oliver Wake, 2013

With thanks to: the BBC Written Archives Centre, the British Film Institute’s Special Collections team, Christopher Perry of Kaleidoscope, and Ian Greaves.

Originally posted: 1 January 2011.

Updates:

7 January 2013: Minor amendments.

11 January 2014: Replaced 2011 post with a new version, with substantial revisions to existing material and the addition of substantial new material including audience research.

4 October 2017: Minor amendments: corrected ‘be hoped’ to ‘been hoped’; amended structure of sentence about Furst playing one role.

11 March 2022: Added material from the Liverpool Echo and Evening Express and Coventry Evening Telegraph; corrected one word for typo.

13 June 2022: Added material from the Jewish Chronicle (added J.F. quotation and surrounding discussion).

Pingback: Stalingrad (1963) – British Television Drama

Pingback: Das BBC-Drama „Dr. Korczak and the Children“ (1962) – Erwin Sylvanus

Pingback: British Television Drama » Blog Archive » The July Plot (1964)