by DAVID ROLINSON

Call the Midwife series two episode five Writer: Heidi Thomas; Director: China Moo-Young

Call the Midwife often makes skilful use of editing to interweave its lead characters with its guest characters. This aids storytelling, heightens our understanding of characters in their social environment and at times even complicates the position of the midwives in that environment. This essay will explore editing and other aspects of form in two sequences from Call the Midwife series two episode five, to explore the ways in which the problems of guest character Nora Harding are interwoven with two lead characters: the first sequence is a well-executed piece of storytelling, whilst the second is an extraordinary use of technique to devastating effect.1

Call the Midwife often makes skilful use of editing to interweave its lead characters with its guest characters. This aids storytelling, heightens our understanding of characters in their social environment and at times even complicates the position of the midwives in that environment. This essay will explore editing and other aspects of form in two sequences from Call the Midwife series two episode five, to explore the ways in which the problems of guest character Nora Harding are interwoven with two lead characters: the first sequence is a well-executed piece of storytelling, whilst the second is an extraordinary use of technique to devastating effect.1

Introduction

Nora Harding (Sharon Small) is married with eight children and is pregnant again but makes it clear to midwife Jenny Lee (Jessica Raine) that she wants to get rid of the baby: this makes Jenny uncomfortable and the systemic limits of her role become clear as her diligent advice about getting contraceptive advice after the birth clashes with her witnessing of Nora’s overcrowded rat-infested flat. The council cannot house eight children – they insist that the family cannot be relocated until a four-bedroom house is available, but they are not building such houses – and the National Health Service does not currently cover contraception. Nora cannot cope and is suicidal. She ultimately takes the only action that she can given the laws of the time: illegal abortion.

In the first sequence covered by this essay, she attempts an old-fashioned remedy. This sequence provides greater understanding of her situation by paralleling her actions with the Nonnatus House nuns singing at Compline, in particular Sister Bernadette (Laura Main). In Film Art: An Introduction, David Bordwell and Kristin Thompson discuss crosscutting as the most common technique through which ‘the plot alternates shots of story events in one place with shots of another event elsewhere’, which can give us us ‘unrestricted knowledge of a situation’ and ‘can clarify conflict and build tension’.2 If crosscutting can generate knowledge, where do these sequences stand on that knowledge? If crosscutting helps to draw parallels, what are those parallels? The upsetting topic under discussion in these sequences means that complex issues are at stake in the discussion of these techniques.

In the second sequence, Nora is visited by an illegal abortionist and a brutal procedure is crosscut with midwife Trixie Franklin (Helen George) attending to her nails, with the graphic relationship between shots and the relationship between sound and image drawing parallels between them. These parallels clarify the unshowable horrors that are being experienced by Nora; however, they also have complex results for our understanding of the characters. The sequences also underline the series’ social anger; as I have already discussed, although it is set in the past and was initially based on Jennifer Worth’s memoirs of working in that period, the series is often topical. For example, this week’s episode in the current 2017 series tackled female genital mutilation (FGM) and the episode under discussion in this essay seems sadly all the more topical given current political discourse around the state regulation of women’s bodies and reproduction.3

Sequence one: ‘Wash me thoroughly from my wickedness’

The first sequence takes us from nuns performing Compline at Nonnatus House to Nora’s attempts to self-administer an abortion with gin and a hot bath, and then back to Compline. Our experience of Compline is centred around the doubts of Sister Bernadette. The blue and yellow palette at Nonnatus House conveys the nighttime setting and suggests that these two actions in different places are happening around the same time. The sequence opens with the camera tracking right to left around a pillar, forming an object wipe. Editing takes us from a position behind the nuns to a position in front of them, a jolt which is eased by graphic continuity – their similar arrangement in the frame – and by the choice of a dissolve between the initial tracking shot and the frontal static shot. During this dissolve, the candle (foregrounded in the first shot) is superimposed over Sister Bernadette: at this stage of the tracking shot the candle has moved left to right to reach the centre of the frame, where Sister Bernadette is located. Although the nuns appear in a balanced frame, Sister Bernadette is prioritised by her placement in the frame and the signposting of that centrality by the dissolve. Call the Midwife is an ensemble drama in which different characters take the lead in different storylines; it seems likely that Sister Bernadette’s perspective will be central to this sequence.

The first sequence takes us from nuns performing Compline at Nonnatus House to Nora’s attempts to self-administer an abortion with gin and a hot bath, and then back to Compline. Our experience of Compline is centred around the doubts of Sister Bernadette. The blue and yellow palette at Nonnatus House conveys the nighttime setting and suggests that these two actions in different places are happening around the same time. The sequence opens with the camera tracking right to left around a pillar, forming an object wipe. Editing takes us from a position behind the nuns to a position in front of them, a jolt which is eased by graphic continuity – their similar arrangement in the frame – and by the choice of a dissolve between the initial tracking shot and the frontal static shot. During this dissolve, the candle (foregrounded in the first shot) is superimposed over Sister Bernadette: at this stage of the tracking shot the candle has moved left to right to reach the centre of the frame, where Sister Bernadette is located. Although the nuns appear in a balanced frame, Sister Bernadette is prioritised by her placement in the frame and the signposting of that centrality by the dissolve. Call the Midwife is an ensemble drama in which different characters take the lead in different storylines; it seems likely that Sister Bernadette’s perspective will be central to this sequence.

A lot of episodes of Call the Midwife make use of sequences like this, that take us from the nuns to a suffering guest character while holding the audio of their sung or spoken words as commentary or blessing. Here, the phrase ‘do away mine offences’ invites a parallel with Nora’s story, and this association is the main motivation for a cut to the Hardings’ kitchen. Holding the sound of Compline develops this parallel and grounds this as crosscutting. There is no establishing shot, so instead we construct offscreen space, having seen the Hardings’ flat earlier in the episode, and having discovered Nora’s situation during the episode (so, in Bordwell and Thompson’s terms this is constructive editing, not analytical editing). Holding the song over the images builds a narrative parallel. A shot of the as-yet-unidentified woman pouring water is accompanied by the line ‘Wash me thoroughly from my wickedness’, and at the end of this line a tilt up reveals, or confirms, that this is Nora. We have hit the content curve: holding a shot long enough to convey the important information, then moving on, in this case to answer questions raised by it. It could only be Nora, given that she is filling a bath with very hot water and we know her situation: the action itself brings together the rhetoric of cleansing, baptism and the action that she is hoping to achieve.

A lot of episodes of Call the Midwife make use of sequences like this, that take us from the nuns to a suffering guest character while holding the audio of their sung or spoken words as commentary or blessing. Here, the phrase ‘do away mine offences’ invites a parallel with Nora’s story, and this association is the main motivation for a cut to the Hardings’ kitchen. Holding the sound of Compline develops this parallel and grounds this as crosscutting. There is no establishing shot, so instead we construct offscreen space, having seen the Hardings’ flat earlier in the episode, and having discovered Nora’s situation during the episode (so, in Bordwell and Thompson’s terms this is constructive editing, not analytical editing). Holding the song over the images builds a narrative parallel. A shot of the as-yet-unidentified woman pouring water is accompanied by the line ‘Wash me thoroughly from my wickedness’, and at the end of this line a tilt up reveals, or confirms, that this is Nora. We have hit the content curve: holding a shot long enough to convey the important information, then moving on, in this case to answer questions raised by it. It could only be Nora, given that she is filling a bath with very hot water and we know her situation: the action itself brings together the rhetoric of cleansing, baptism and the action that she is hoping to achieve.

The medium close-up of Nora is held for the line ‘and cleanse me from my sin’. This is a reminder that it can be dangerous to make over-literal readings of relationships between words and images in sequences cut to songs.4 The parallel established here is neither Nora’s own view nor the series’ judgement of her situation: crosscutting here is critical of discourse on abortion (we know her circumstances, know the social context and know that she needs help that she cannot get). The last note of the line is held over a jump cut to a few moments later as she fills another bowl of water. Operating more as montage, this moment provides a brief ellipsis in the narrative but not in the song.

The medium close-up of Nora is held for the line ‘and cleanse me from my sin’. This is a reminder that it can be dangerous to make over-literal readings of relationships between words and images in sequences cut to songs.4 The parallel established here is neither Nora’s own view nor the series’ judgement of her situation: crosscutting here is critical of discourse on abortion (we know her circumstances, know the social context and know that she needs help that she cannot get). The last note of the line is held over a jump cut to a few moments later as she fills another bowl of water. Operating more as montage, this moment provides a brief ellipsis in the narrative but not in the song.

Nora stares offscreen as we hear another line: ‘For I acknowledge my faults and my sin is ever before me’. From our constructed sense of space, we infer that she is looking at the bath or even the baby’s cot. She seems deep in thought, but we do not have access to her unspoken words unless we problematically infer that the song speaks for her, as if she has internalised the rhetoric of sin. Just after ‘sin’ and before ‘before me’, there is a straight cut back to Compline. This part of the sequence echoes the start of the sequence: there is another cheat wipe round an object, this time tracking left to right, and another cut from behind the nuns to in front of them (to argue that this violates the 180 degree rule would be to understate the extent to which this has become conventional screen grammar and to oversimplify the ways in which that line is constantly redrawn), this time a cut instead of a dissolve. The repetition of compositions and editing strategies marks a pattern that places Sister Bernadette at the centre of a sequence that has so far prioritised, but provided limited agency to, Nora. However, the pattern connects Sister Bernadette (better-known to viewers of later series as Shelagh) and Nora through graphic similarities: the central framing of the candle, which connected it with Sister Bernadette earlier in the sequence, resembles our previous view of Nora in the colour palette established by mise-en-scène (in particular, curtains and her clothing).

Nora stares offscreen as we hear another line: ‘For I acknowledge my faults and my sin is ever before me’. From our constructed sense of space, we infer that she is looking at the bath or even the baby’s cot. She seems deep in thought, but we do not have access to her unspoken words unless we problematically infer that the song speaks for her, as if she has internalised the rhetoric of sin. Just after ‘sin’ and before ‘before me’, there is a straight cut back to Compline. This part of the sequence echoes the start of the sequence: there is another cheat wipe round an object, this time tracking left to right, and another cut from behind the nuns to in front of them (to argue that this violates the 180 degree rule would be to understate the extent to which this has become conventional screen grammar and to oversimplify the ways in which that line is constantly redrawn), this time a cut instead of a dissolve. The repetition of compositions and editing strategies marks a pattern that places Sister Bernadette at the centre of a sequence that has so far prioritised, but provided limited agency to, Nora. However, the pattern connects Sister Bernadette (better-known to viewers of later series as Shelagh) and Nora through graphic similarities: the central framing of the candle, which connected it with Sister Bernadette earlier in the sequence, resembles our previous view of Nora in the colour palette established by mise-en-scène (in particular, curtains and her clothing).

On the line ‘And shalt make me to understand wisdom secretly’ the camera does something different from earlier in the sequence: it tracks in slightly on Sister Bernadette, picking her out of the group to underline the doubts conveyed by her small, distracted look up. At this moment the diegetic singing is replaced by non-diegetic music: this is a moment of reflection for Sister Bernadette, her perspective. Sister Bernadette has her own concerns about her calling: she believes that she can do more good in nursing. The parallel therefore says as much about her own situation as Nora’s. If the narrative connection between them is not clear in this sequence, the thematic connection is. The sequence now returns to Nora: she is now in the bath, needing to perform this action in secret, separated from help that she cannot ask for. From that medium close-up we cut, at last, to an establishing shot. Formal and confining, the shot conveys the situation – with details such as the bottle of gin on the chair – and returns Nora’s actions to the context of her circumstances. She sits in the bath, in the room that is too small, with the cot that she does not want to fill, appearing as a set of imprisoning bars (were we to see a shot from Nora’s optical point-of-view, we would see the bars). In this shot, the Harding home looks different from how it looks in most of the episode, as we can see by leaving this sequence:

On the line ‘And shalt make me to understand wisdom secretly’ the camera does something different from earlier in the sequence: it tracks in slightly on Sister Bernadette, picking her out of the group to underline the doubts conveyed by her small, distracted look up. At this moment the diegetic singing is replaced by non-diegetic music: this is a moment of reflection for Sister Bernadette, her perspective. Sister Bernadette has her own concerns about her calling: she believes that she can do more good in nursing. The parallel therefore says as much about her own situation as Nora’s. If the narrative connection between them is not clear in this sequence, the thematic connection is. The sequence now returns to Nora: she is now in the bath, needing to perform this action in secret, separated from help that she cannot ask for. From that medium close-up we cut, at last, to an establishing shot. Formal and confining, the shot conveys the situation – with details such as the bottle of gin on the chair – and returns Nora’s actions to the context of her circumstances. She sits in the bath, in the room that is too small, with the cot that she does not want to fill, appearing as a set of imprisoning bars (were we to see a shot from Nora’s optical point-of-view, we would see the bars). In this shot, the Harding home looks different from how it looks in most of the episode, as we can see by leaving this sequence:

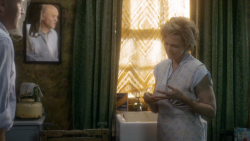

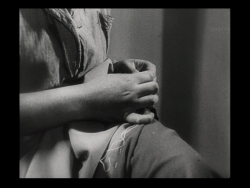

Elsewhere in the episode, space in the Harding home is contracted by different shot sizes, lens choices and the foregrounding of children to clutter the frame. Most of the activity of the home takes place within one space, as laundry hangs over the stove and cot, behind the family meal and beside the sink. A wall-mounted mirror reflects the laundry and adds to the claustrophobia. Similarly, her husband competes with laundry in the reflection from the mirror as he takes in his wife’s plan to sell their wedding ring: at this point her gaze avoids his, as she looks down at the extension of her fingers in a gesture that will be echoed by Trixie later in the episode.

Elsewhere in the episode, space in the Harding home is contracted by different shot sizes, lens choices and the foregrounding of children to clutter the frame. Most of the activity of the home takes place within one space, as laundry hangs over the stove and cot, behind the family meal and beside the sink. A wall-mounted mirror reflects the laundry and adds to the claustrophobia. Similarly, her husband competes with laundry in the reflection from the mirror as he takes in his wife’s plan to sell their wedding ring: at this point her gaze avoids his, as she looks down at the extension of her fingers in a gesture that will be echoed by Trixie later in the episode.

If crosscutting between Nora’s space and Nonnatus House serves an editorialising function then it generates sympathy and a critique of the context in which Nora finds herself without options. Later, Sister Julienne (Jenny Agutter) advises Jenny that ‘We can give only love and encouragement. And warning.’ For Jenny, this is not enough: ‘She kept asking for help that we couldn’t give her. For contraception, for sterilisation even.’

Sequence two: ‘You saw me standing alone’

Some of the themes from the Nora/Sister Bernadette sequence are picked up in a later sequence, but this second sequence operates in surprising ways. While Trixie gets ready for a romantic night out, Nora undergoes an illegal abortion. This is an astonishing sequence. Although it contains no graphic detail, the logic of crosscutting makes it very difficult to watch. Although it is only two minutes long, it is more rich in detail than this short account can convey. We move between two domestic spaces. Nora’s family dining table becomes an operating table staffed by people who should not be doing this. At a kitchen table, Trixie, a qualified professional, does her nails, unaware of Nora’s experience and unable to help.

Trixie appears in near-profile, centre-right of frame in a medium-shot whose shallow focus isolates her from her background: the lens and chiaroscuro make strange the usually warm and safe space of Nonnatus House. Put simply, Nonnatus House has never looked like this before or since. This is partly a marker of the impressive visual style of director China Moo-Young and the work of director of photography Simon Archer, but it also raises the question of how spaces operate in drama series. As Lucy Fife Donaldson observes in her discussion of the first four series of Inspector Morse, regular visits to domestic spaces involve repetition and rearticulation, moments of familiarity and difference; her discussion draws from Billy Smart’s attention to ‘spatial restriction, the formations of patterns, embellishment and their interruption’ in complete series, and Amy Holdsworth’s attention to television’s moments of return.5 Spaces can change for practical reasons too – the recurring sets in Doctor Who and Steptoe and Son sometimes changed on a weekly basis, gaining and losing features to suit the requirements of the stories or available space in the studio – and to mark shifts in tone.

Trixie appears in near-profile, centre-right of frame in a medium-shot whose shallow focus isolates her from her background: the lens and chiaroscuro make strange the usually warm and safe space of Nonnatus House. Put simply, Nonnatus House has never looked like this before or since. This is partly a marker of the impressive visual style of director China Moo-Young and the work of director of photography Simon Archer, but it also raises the question of how spaces operate in drama series. As Lucy Fife Donaldson observes in her discussion of the first four series of Inspector Morse, regular visits to domestic spaces involve repetition and rearticulation, moments of familiarity and difference; her discussion draws from Billy Smart’s attention to ‘spatial restriction, the formations of patterns, embellishment and their interruption’ in complete series, and Amy Holdsworth’s attention to television’s moments of return.5 Spaces can change for practical reasons too – the recurring sets in Doctor Who and Steptoe and Son sometimes changed on a weekly basis, gaining and losing features to suit the requirements of the stories or available space in the studio – and to mark shifts in tone.

In this shot Trixie is made strange just as she is made over, and the technique isolates the acts by which she constructs her sense of self through her/a sense of femininity. Trixie often defines herself by her attentiveness to fashion and to film stars in their textual and paratextual costumes and acts of embodiment, which she communicates to colleagues and patients as the correct way to extend an arm or hold her posture; indeed, elsewhere in the episode she manages the feat of elegantly combining a cigarette and cocktail glass in one hand while reading about stars. At the start of the sequence Trixie is not complete: usually nobody puts Trixie in the corner, but her off-centre framing at a table surrounded by empty chairs does just that. For once she melts into the background, as her costume so closely resembles the tablecloth and the far wall of the room, from which she is distinguished only by backlighting and the dark detail of and behind the doorframe. Trixie’s hands are highlighted by a diagonal shaft of light in the background which is motivated by light coming through the doorway. Different techniques will isolate her hands from the rest of her as the sequence continues. Trixie’s tools of gendered labour sit in front of her, more central in the frame and positioned at the end of the light: her nail kit. Music will again connect the two strands of the sequence: this time the song ‘Blue Moon’, initially presented as diegetic music from the radio in the kitchen, will bridge Trixie and Nora’s experiences. ‘You saw me standing alone’: we have, but if all goes as well as Trixie hopes, she won’t be alone for long. The camera starts to track in as she prepares her hands. A cut interrupts the camera movement.

Nora, facing up to the reality of the illegal abortion which she is about to undertake, puts her hand to her face. The cut takes us between two sets of hand movement: Trixie’s outward-facing confident hand extension to Nora’s small display of internal conflict. This is not a match-cut, because there is such graphic discontinuity between the two compositions and the actions are different,6 but we cut on action to emphasise similarities not only in gesture but in costume, hair and hand movement. The camera here tracks out, reversing the movement into Trixie, as another line of the song serves as comment: ‘without a dream in my heart’. In a frontal shot, Nora perches on the table. The space is again subtly different from its earlier appearance as the composition crops width but isolates Nora from the room through a shift in depth of field (we seem further away from the sink). Cutting back to Trixie, attending to her nails, and then back to the Harding home, emphasises differences in composition and lighting. We return to Nora in close-up, asking for a drink to settle her nerves. There is a cut back to a frontal medium-shot echoing one from earlier in the sequence, a movement back to a more formal composition which centres the shot around Nora’s experience while also restricting her space. Each of the three women occupies a third of the frame, each highlighted against the background by rim lighting that compliments mise-en-scène: the laundry for Miriam Pritchard (Charlotte Victoria), the young woman on the left (continuing the colour of her blouse lower in the frame but distinct from her red hair), the sheet placed at the window for privacy (echoing Nora’s blonde hair, popping against her blue top and forming a darker shade than the sunnily back-lit net curtain seen earlier in the episode) and the green curtains and murky walls behind Mrs Pritchard (Alison Newman), the abortionist (dressed in greens and browns). The laundry forms a diagonal white line only distantly related to the diagonal ray of light behind Trixie earlier in the sequence. Visual correlations between the two scenes will escalate from here.

Nora, facing up to the reality of the illegal abortion which she is about to undertake, puts her hand to her face. The cut takes us between two sets of hand movement: Trixie’s outward-facing confident hand extension to Nora’s small display of internal conflict. This is not a match-cut, because there is such graphic discontinuity between the two compositions and the actions are different,6 but we cut on action to emphasise similarities not only in gesture but in costume, hair and hand movement. The camera here tracks out, reversing the movement into Trixie, as another line of the song serves as comment: ‘without a dream in my heart’. In a frontal shot, Nora perches on the table. The space is again subtly different from its earlier appearance as the composition crops width but isolates Nora from the room through a shift in depth of field (we seem further away from the sink). Cutting back to Trixie, attending to her nails, and then back to the Harding home, emphasises differences in composition and lighting. We return to Nora in close-up, asking for a drink to settle her nerves. There is a cut back to a frontal medium-shot echoing one from earlier in the sequence, a movement back to a more formal composition which centres the shot around Nora’s experience while also restricting her space. Each of the three women occupies a third of the frame, each highlighted against the background by rim lighting that compliments mise-en-scène: the laundry for Miriam Pritchard (Charlotte Victoria), the young woman on the left (continuing the colour of her blouse lower in the frame but distinct from her red hair), the sheet placed at the window for privacy (echoing Nora’s blonde hair, popping against her blue top and forming a darker shade than the sunnily back-lit net curtain seen earlier in the episode) and the green curtains and murky walls behind Mrs Pritchard (Alison Newman), the abortionist (dressed in greens and browns). The laundry forms a diagonal white line only distantly related to the diagonal ray of light behind Trixie earlier in the sequence. Visual correlations between the two scenes will escalate from here.

Two more cuts take us back to Nora taking in what is about to happen and then to a shot from behind as Nora begins to lose control of events: now the camera moves to accommodate Mrs Pritchard’s movement to a different position and she tells Nora to lay back. This is not an optical point-of-view shot, but is as close as we have been to sharing her physical position; the sequence uses other means to convey her perspective (her point of view, not her optical point-of-view). There is then a cut back to Trixie, and though this is not quite a match-cut (the shot size and lens mark Trixie differently) there are visual similarities: both look right to left, there is similar camera movement, and the graphic relationship between the two shots places Trixie where she would be if she was present, helping to deliver Nora’s baby. The language of shot/reverse-shot – the reverse-field pattern – need not be restricted to two people speaking to each other in the same room,7 but the association of midwife Trixie’s visual position with that of the abortionist is troubling.

Two more cuts take us back to Nora taking in what is about to happen and then to a shot from behind as Nora begins to lose control of events: now the camera moves to accommodate Mrs Pritchard’s movement to a different position and she tells Nora to lay back. This is not an optical point-of-view shot, but is as close as we have been to sharing her physical position; the sequence uses other means to convey her perspective (her point of view, not her optical point-of-view). There is then a cut back to Trixie, and though this is not quite a match-cut (the shot size and lens mark Trixie differently) there are visual similarities: both look right to left, there is similar camera movement, and the graphic relationship between the two shots places Trixie where she would be if she was present, helping to deliver Nora’s baby. The language of shot/reverse-shot – the reverse-field pattern – need not be restricted to two people speaking to each other in the same room,7 but the association of midwife Trixie’s visual position with that of the abortionist is troubling.

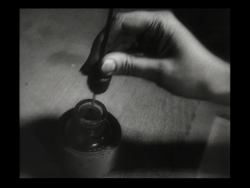

There is a cut – on character movement – between mobile shots of Trixie and Nora. During the close-up of Trixie the camera made a small move left to right and, as Nora lies back on the table, the camera moves up and left to accommodate her movement. The sequence cuts to a shot of the abortionists’ tools. This shot is not Nora’s optical point-of-view but is consistent with her perspective, her place in the space. As Miriam passes tools across to the abortionist, the hands of all three women are present in the frame. In the films of Robert Bresson, hands are often isolated from their characters as if the acts are disembodied,8 and here the display of the tools in isolation from all but the exposed flesh of the characters’ hands places them firmly in memory in the lead-in to an operation during which they will be a defining absence, as the only tools shown on screen will be those used by Trixie.

There is a cut – on character movement – between mobile shots of Trixie and Nora. During the close-up of Trixie the camera made a small move left to right and, as Nora lies back on the table, the camera moves up and left to accommodate her movement. The sequence cuts to a shot of the abortionists’ tools. This shot is not Nora’s optical point-of-view but is consistent with her perspective, her place in the space. As Miriam passes tools across to the abortionist, the hands of all three women are present in the frame. In the films of Robert Bresson, hands are often isolated from their characters as if the acts are disembodied,8 and here the display of the tools in isolation from all but the exposed flesh of the characters’ hands places them firmly in memory in the lead-in to an operation during which they will be a defining absence, as the only tools shown on screen will be those used by Trixie.

There are several cuts between the abortionist and Nora. The medium-shot of Mrs Pritchard standing between Nora’s legs is taken from a camera position that is more recognisable from sequences of deliveries elsewhere in the series: this step back from the closer shot of the tools is therefore familiar but reaffirms the absence of the qualified staff who would ordinarily be in such a shot. There is then a big close-up of Trixie’s hands: her nails and, in the other hand, one of her own tools. Even more shallow depth of field renders a pair of scissors blurry in the background and their presence echoes the devices seen in the abortionist’s toolkit, underlining an association between tools of gendered labour.

There are several cuts between the abortionist and Nora. The medium-shot of Mrs Pritchard standing between Nora’s legs is taken from a camera position that is more recognisable from sequences of deliveries elsewhere in the series: this step back from the closer shot of the tools is therefore familiar but reaffirms the absence of the qualified staff who would ordinarily be in such a shot. There is then a big close-up of Trixie’s hands: her nails and, in the other hand, one of her own tools. Even more shallow depth of field renders a pair of scissors blurry in the background and their presence echoes the devices seen in the abortionist’s toolkit, underlining an association between tools of gendered labour.

Then, disturbingly, over a big close-up of Trixie scraping her fingernail, we hear Nora gasp. In narrative terms, Trixie’s scrape does not cause Nora to gasp. The sound bridge serves a thematic function: the moment is disturbing because it sets up an association between Trixie’s action (depicted in close-up detail and repeated, driving up into the skin above the nail) and the actions of the abortionist (which are unpresentable visually or aurally). The use of technique deviates from conventional storytelling in ways that become troubling when you stop to consider whose perspective guides this sequence. (The question ‘who is hearing this?’ may seem strange but it may help us to consider where the sequence stands on Trixie, a question to which this essay will return.) ‘Blue Moon’ is established as external diegetic sound for Trixie (its source in the story world is the radio in her room) but continues over the Trixie and Nora parts of the sequence (it could be internal diegetic for Nora, for example a song that she associates with, but the pitch and timbre remain consistent across the sequence). If the sound of Trixie’s scraping was held over a shot of Nora’s reaction, the volume, pitch and timbre would be consistent with the closeness of the shot of Trixie’s hand and therefore in excess of Nora’s auditory range, and therefore easier to assess as internal diegetic or as a sign of her mental subjectivity. However, this way round, it would be difficult to see Nora’s reaction as a feature of Trixie’s mental subjectivity, even though it combines with ‘Blue Moon’. The gasp is diegetic to Nora: the sound bridge is associative. In the logic of crosscutting, the scenes may be synchronous in terms of time but not space. If the use of a song with romantic connotations is jarring, both music and sound effects connect the event with Trixie, which is all more troubling because it makes her a constant presence, which in turn only emphasises her absence.

Then, disturbingly, over a big close-up of Trixie scraping her fingernail, we hear Nora gasp. In narrative terms, Trixie’s scrape does not cause Nora to gasp. The sound bridge serves a thematic function: the moment is disturbing because it sets up an association between Trixie’s action (depicted in close-up detail and repeated, driving up into the skin above the nail) and the actions of the abortionist (which are unpresentable visually or aurally). The use of technique deviates from conventional storytelling in ways that become troubling when you stop to consider whose perspective guides this sequence. (The question ‘who is hearing this?’ may seem strange but it may help us to consider where the sequence stands on Trixie, a question to which this essay will return.) ‘Blue Moon’ is established as external diegetic sound for Trixie (its source in the story world is the radio in her room) but continues over the Trixie and Nora parts of the sequence (it could be internal diegetic for Nora, for example a song that she associates with, but the pitch and timbre remain consistent across the sequence). If the sound of Trixie’s scraping was held over a shot of Nora’s reaction, the volume, pitch and timbre would be consistent with the closeness of the shot of Trixie’s hand and therefore in excess of Nora’s auditory range, and therefore easier to assess as internal diegetic or as a sign of her mental subjectivity. However, this way round, it would be difficult to see Nora’s reaction as a feature of Trixie’s mental subjectivity, even though it combines with ‘Blue Moon’. The gasp is diegetic to Nora: the sound bridge is associative. In the logic of crosscutting, the scenes may be synchronous in terms of time but not space. If the use of a song with romantic connotations is jarring, both music and sound effects connect the event with Trixie, which is all more troubling because it makes her a constant presence, which in turn only emphasises her absence.

A few shots later, there is another close-up as Trixie files her nails, and now the sound is entirely diegetic, with nothing heard from Nora, but no less disturbing because the association has been established, making the quick, jagged movements and sound effects (both heightened by such close scrutiny) seem violent. The camera’s angle on Trixie’s fingers is consistent with the angle from which Nora would be framed if Mrs Pritchard’s actions could be shown openly through third-person narration. There is a cut to Nora in profile, writhing on the table, and back to Mrs Pritchard performing actions that are beyond our vision. The sound of Nora gasping bridges a cut from Mrs Pritchard back to Trixie, this time trimming her nail with scissors. This time, in a less close close-up, part of Trixie’s face is in shot, but acknowledging this does not reduce the impact of the association. Trixie is again roughly consistent with Mrs Pritchard’s position in relation to Nora in the other strand. The lens keeps Trixie’s hands as the primary content of the shot: isolating her hands from the rest of her and from the room. During the crosscutting between Trixie and Nora, the temporal relationships are maintained: each of the two strands has ellipses progressing along parallel lines of abbreviated action.

A few shots later, there is another close-up as Trixie files her nails, and now the sound is entirely diegetic, with nothing heard from Nora, but no less disturbing because the association has been established, making the quick, jagged movements and sound effects (both heightened by such close scrutiny) seem violent. The camera’s angle on Trixie’s fingers is consistent with the angle from which Nora would be framed if Mrs Pritchard’s actions could be shown openly through third-person narration. There is a cut to Nora in profile, writhing on the table, and back to Mrs Pritchard performing actions that are beyond our vision. The sound of Nora gasping bridges a cut from Mrs Pritchard back to Trixie, this time trimming her nail with scissors. This time, in a less close close-up, part of Trixie’s face is in shot, but acknowledging this does not reduce the impact of the association. Trixie is again roughly consistent with Mrs Pritchard’s position in relation to Nora in the other strand. The lens keeps Trixie’s hands as the primary content of the shot: isolating her hands from the rest of her and from the room. During the crosscutting between Trixie and Nora, the temporal relationships are maintained: each of the two strands has ellipses progressing along parallel lines of abbreviated action.

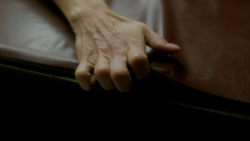

This combination continues. From Trixie’s actions with her scissors we cut to Nora crying out in pain: this time the sound is accompanied by a close-up of her hand grasping the sheet and table below her. There is another parallel as, again bridged by Nora’s gasps, we cut from Nora’s clenching fist to a big close-up of Trixie’s outstretched hand as she paints one of her fingernails a sudden streak of blood red. Two quick cuts show Nora contorting and Trixie painting other nails.

This combination continues. From Trixie’s actions with her scissors we cut to Nora crying out in pain: this time the sound is accompanied by a close-up of her hand grasping the sheet and table below her. There is another parallel as, again bridged by Nora’s gasps, we cut from Nora’s clenching fist to a big close-up of Trixie’s outstretched hand as she paints one of her fingernails a sudden streak of blood red. Two quick cuts show Nora contorting and Trixie painting other nails.

There is then an abrupt cut back to Nora, shot in profile from the same height as her, as she puts a cloth into her mouth in order to bite on it and muffle her cries of pain. Now a cut from Nora to behind the abortionist, reaffirming the spatial and temporal relationship between shots: Trixie’s actions are not causing this but are standing in for the abortionist’s actions just as the abortionist is standing in for professional help. Nora’s cries of pain are louder and more prolonged. The camera gently moves back. (Breaking down a sequence like this in terms of technical details is a slightly inhuman but manageable way of coming to terms with something that I find so disturbing every time I see it.)

There is then an abrupt cut back to Nora, shot in profile from the same height as her, as she puts a cloth into her mouth in order to bite on it and muffle her cries of pain. Now a cut from Nora to behind the abortionist, reaffirming the spatial and temporal relationship between shots: Trixie’s actions are not causing this but are standing in for the abortionist’s actions just as the abortionist is standing in for professional help. Nora’s cries of pain are louder and more prolonged. The camera gently moves back. (Breaking down a sequence like this in terms of technical details is a slightly inhuman but manageable way of coming to terms with something that I find so disturbing every time I see it.)

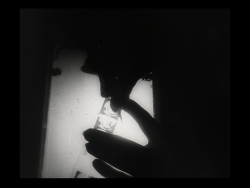

From that shot we move between three shots of Trixie. Firstly, a return to the establishing shot from the start of the sequence, with Trixie in medium-shot dipping her nail varnish brush into the bottle. Secondly, as a form of staggered zoom, a jump to a close shot as Trixie, now disembodied in the frame, removes the brush and moves it towards herself. Thirdly, a close-up on the cloth that Trixie has placed over her section of the tablecloth: between her nail files and her painted nails drops…

From that shot we move between three shots of Trixie. Firstly, a return to the establishing shot from the start of the sequence, with Trixie in medium-shot dipping her nail varnish brush into the bottle. Secondly, as a form of staggered zoom, a jump to a close shot as Trixie, now disembodied in the frame, removes the brush and moves it towards herself. Thirdly, a close-up on the cloth that Trixie has placed over her section of the tablecloth: between her nail files and her painted nails drops…

…a circle of blood-red nail varnish. The shot is held briefly as the blob glistens, then there is a cut to a different surface: a floor. There is one drop of blood red already there, and now a second drop falls to join it. Unlike the nail varnish, this is not a metonym. This is blood. At the drop of blood, ‘Blue Moon’ stops. Trixie’s absence from Nora’s world becomes complete. Mrs Pritchard’s voice bridges this shot and a group shot that makes it clear that this blood is Nora’s. In both sequences discussed in this essay, care is absent. Hannah Hamad has placed television depictions of nursing in the context of ‘a broader “affective turn” towards sociocultural revaluations’ of ‘women’s work’ and ’emotional labour’,9 which is taking place at ‘a moment of crisis for nursing’ in which nurses, and ‘the perceived erosion of practical and affective skills’ are blamed for the failings of ‘a technologized, neo-liberalized and privatized NHS’.10 It therefore appears as though substantial issues are at stake when the absence of care is explored in this way.

…a circle of blood-red nail varnish. The shot is held briefly as the blob glistens, then there is a cut to a different surface: a floor. There is one drop of blood red already there, and now a second drop falls to join it. Unlike the nail varnish, this is not a metonym. This is blood. At the drop of blood, ‘Blue Moon’ stops. Trixie’s absence from Nora’s world becomes complete. Mrs Pritchard’s voice bridges this shot and a group shot that makes it clear that this blood is Nora’s. In both sequences discussed in this essay, care is absent. Hannah Hamad has placed television depictions of nursing in the context of ‘a broader “affective turn” towards sociocultural revaluations’ of ‘women’s work’ and ’emotional labour’,9 which is taking place at ‘a moment of crisis for nursing’ in which nurses, and ‘the perceived erosion of practical and affective skills’ are blamed for the failings of ‘a technologized, neo-liberalized and privatized NHS’.10 It therefore appears as though substantial issues are at stake when the absence of care is explored in this way.

The abortionist describes the flow of blood as ‘very cleansing’, which returns us to the language of sin from the earlier sequence. The comparison between Trixie and Nora continues at the very end of the sequence: from Nora’s legs in bed to Trixie’s legs in heels as she reaches her appointment. The sequence that ends with Trixie’s legs – criss-cross, in the rhetoric of the disembodied legs which are crosscut at the start of Hitchcock’s Strangers on a Train – emphasises that Trixie is more free than Nora, but also forewarns that Trixie may be in for an upsetting date.

The abortionist describes the flow of blood as ‘very cleansing’, which returns us to the language of sin from the earlier sequence. The comparison between Trixie and Nora continues at the very end of the sequence: from Nora’s legs in bed to Trixie’s legs in heels as she reaches her appointment. The sequence that ends with Trixie’s legs – criss-cross, in the rhetoric of the disembodied legs which are crosscut at the start of Hitchcock’s Strangers on a Train – emphasises that Trixie is more free than Nora, but also forewarns that Trixie may be in for an upsetting date.

For me, this sequence connects women through gendered labour and the socially-constructed performance of gender. It emphasises Trixie’s obsession with embodiment – she articulates herself through her body rather than confronting issues like her alcoholism – and shows that the series is aware of the intersections between class and gender. However, recent studies of the series have taken a more critical view of its class dimensions. Estella Tincknell argued that ‘Call the Midwife breaks with the paternalism validated by Downton Abbey to suggest that postwar society offered ordinary women opportunities for agency and independence’ and ‘presents a call to arms for socialised medicine – that peculiarly British articulation of socialism’.11 However, Tincknell also noted that the series ‘privilege[s] the expertise of the nurses and nuns’, and that ‘the dominant figures and values are middle class’.12 For Hannah Hamad, Call the Midwife is ‘less a depiction of the reality of women’s work’ and, as quoted in my previous essay on the series, ‘more a remediation of past fantasies and cultural constructions of nursing, which configure nursing according to “an all-embracing ideal of white, middle-class femininity”’.13 If we accept these views, the use of crosscutting in this sequence seems potentially problematic.

Is the sequence critical of Trixie? She sits and beautifies herself, unaware of the suffering of a woman who lacks her options. There are precedents for critical crosscutting around details like the ones in this sequence. Dziga Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera (1929) crosscuts between women having their nails done and women working, forming a critical juxtaposition that depicts women receiving beauty treatment as relics of Lenin’s New Economic Policy and contrasts them with working women in manual labour, women working in factories in embodied rhythms indistinguishable from machines, and Elizaveta Svilova editing this very film (presenting filmmaking as another example of mechanized labour as Vertov’s film reflexively engages with its own construction).14 The film heightens associations through technique, for example in rhymed shots of hand movements with scissors on hair and film.

Is the sequence critical of Trixie? She sits and beautifies herself, unaware of the suffering of a woman who lacks her options. There are precedents for critical crosscutting around details like the ones in this sequence. Dziga Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera (1929) crosscuts between women having their nails done and women working, forming a critical juxtaposition that depicts women receiving beauty treatment as relics of Lenin’s New Economic Policy and contrasts them with working women in manual labour, women working in factories in embodied rhythms indistinguishable from machines, and Elizaveta Svilova editing this very film (presenting filmmaking as another example of mechanized labour as Vertov’s film reflexively engages with its own construction).14 The film heightens associations through technique, for example in rhymed shots of hand movements with scissors on hair and film.

That editing logic resembles moments of this sequence from Call the Midwife (as do other moments, such as a dip into a pot, though in Man with a Movie Camera that was to connect pieces of film). Call the Midwife is clearly not making an ideological critique directly comparable with the attack made by Man with a Movie Camera on a character’s bourgeois lapse from the goals of revolution. However, correspondences in technique are intriguing given criticisms of the series’ class position quoted above.

That editing logic resembles moments of this sequence from Call the Midwife (as do other moments, such as a dip into a pot, though in Man with a Movie Camera that was to connect pieces of film). Call the Midwife is clearly not making an ideological critique directly comparable with the attack made by Man with a Movie Camera on a character’s bourgeois lapse from the goals of revolution. However, correspondences in technique are intriguing given criticisms of the series’ class position quoted above.

For me, those criticisms underestimate the complexity of the class dynamic in the series. Certainly in its early years, the series presented a regular cast of middle-class, upper-middle-class and upper-class women who had never experienced the sort of conditions lived by working-class women in Poplar. They were often marked as other by the residents, either negatively or positively, and their fish-out-of-water position made them useful identification figures for contemporary viewers (of various class backgrounds) sheltered from these conditions and practices (by time) in ways comparable with the characters’ sheltering (by class). Misreadings of the series as twee or nostalgic have related its depictions of class to its style.

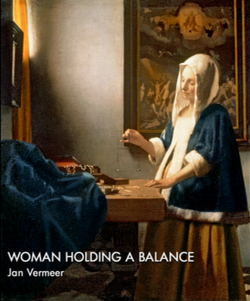

For example, Estella Tincknell observes a newspaper critic’s comparison between the style of Call the Midwife and the paintings of Vermeer, which Tincknell sees as an accusation that ‘the programme’s aesthetics are over-ambitious’ for a drama of this type. In defence, Tincknell argues that the series ‘refuses to reproduce the conventional grimy aesthetic of social realism that has become conflated with representations of working-class experience.’15 This makes Call the Midwife an extension of ‘the new social realism’, a trend for stylistic innovation in popular forms as a solution to the perception that British television cannot or will not ‘continue to tell stories using the old naturalist/realist forms prevalent in the 1960s and 1970s’.16 The comparison with Vermeer recalls the approach taken by director of photography Jack Cardiff to the Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger film Black Narcissus (1948), another text about an order of nuns working in a different environment. Cardiff often related cinematography to painting – ‘light is the principal agent for both’ – and the documentary Cameraman: The Life and Work of Jack Cardiff compared an image from the film with a Vermeer painting (above).17 There are several stylistic touches in this episode of Call the Midwife which recall moments in Black Narcissus: even in the two sequences discussed above, there is the track round an object into the Chapel (one discovers Sister Clodagh at a key moment leading up the film’s climax), the dissolve that underlines Sister Bernadette’s conflicted sense of identity (a dazzling slow dissolve bridges Sister Clodagh’s past romance and present devotion), the sudden, shocking presence of red in Trixie’s nail varnish (a distant cousin of the operatic flourish of Sister Ruth’s lipstick) and even the climactic single drops of nail varnish and blood (just as a few hand-administered splashes of water herald the storms at the film’s close). These observations go beyond questions of influence (there are clearer antecedents such as the saturation of the frame following drops of red on white in Hitchcock’s Marnie). Instead, following Tincknell, they help to question critical expectations of how certain groups are entitled to be treated.

For example, Estella Tincknell observes a newspaper critic’s comparison between the style of Call the Midwife and the paintings of Vermeer, which Tincknell sees as an accusation that ‘the programme’s aesthetics are over-ambitious’ for a drama of this type. In defence, Tincknell argues that the series ‘refuses to reproduce the conventional grimy aesthetic of social realism that has become conflated with representations of working-class experience.’15 This makes Call the Midwife an extension of ‘the new social realism’, a trend for stylistic innovation in popular forms as a solution to the perception that British television cannot or will not ‘continue to tell stories using the old naturalist/realist forms prevalent in the 1960s and 1970s’.16 The comparison with Vermeer recalls the approach taken by director of photography Jack Cardiff to the Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger film Black Narcissus (1948), another text about an order of nuns working in a different environment. Cardiff often related cinematography to painting – ‘light is the principal agent for both’ – and the documentary Cameraman: The Life and Work of Jack Cardiff compared an image from the film with a Vermeer painting (above).17 There are several stylistic touches in this episode of Call the Midwife which recall moments in Black Narcissus: even in the two sequences discussed above, there is the track round an object into the Chapel (one discovers Sister Clodagh at a key moment leading up the film’s climax), the dissolve that underlines Sister Bernadette’s conflicted sense of identity (a dazzling slow dissolve bridges Sister Clodagh’s past romance and present devotion), the sudden, shocking presence of red in Trixie’s nail varnish (a distant cousin of the operatic flourish of Sister Ruth’s lipstick) and even the climactic single drops of nail varnish and blood (just as a few hand-administered splashes of water herald the storms at the film’s close). These observations go beyond questions of influence (there are clearer antecedents such as the saturation of the frame following drops of red on white in Hitchcock’s Marnie). Instead, following Tincknell, they help to question critical expectations of how certain groups are entitled to be treated.

It is true that the series does not always smoothly resolve or even at times address its own class tensions, but the sequences discussed above demonstrate that the series at times problematises the ‘ideal of white, middle-class femininity’. There are storylines in which those values are shown to be inadequate to understanding the needs of working-class women in Poplar. One of the series’ early tropes involves Jenny Lee learning from, as much as educating, mothers in her care; in this episode, Jenny advises Mr Harding that Nora should be more careful in case she accidentally injures herself again, which is a pointed comment that expresses her awareness of what Nora is trying to do and frustration at not being able to prevent the unfolding situation. After Nora ends up seriously ill in hospital as a result of her surgery, Jenny is upset at not being able to help and uncertain about what she could have done. Nora’s recovery is connected with the family’s relocation to better accommodation (represented by the family moving freely on green fields) as concerted effort by the state affects a solution. Mature Jenny (the voice of Vanessa Redgrave) looks back on these events from the present day, in a speech that discounts the rhetoric of sin featured earlier in the episode and resolves the enforced absence of help by drawing a powerful parallel of its own:

Nora’s life was saved by doctors who asked no questions. […] Free, reliable contraception came too late to help her, but in time the scientists triumphed: her daughters’ and granddaughters’ lives remain transfigured long after Man left fleeting footprints on the Moon.

Hamad’s point runs deeper than a critique of class depiction, attempting to engage directly with the series’ intervention in current debates: she argues that the series’ ‘retrospective valorization of what the media elsewhere presents as lost standards of care’ makes it ‘indirectly complicit in negotiating discursive excoriations of today’s nurses, by presenting embodiments of an irretrievable ideal.’18 To accept that argument in relation to the sequences discussed above would require a different analysis of the episode’s absences and its two-way gaze (the ways in which it looks to before the NHS and forward to the threats that the NHS currently faces). The second sequence discussed above makes it difficult for me to accept that reading of the series – which underlines the series’ concern to place socialised medicine in cultural and political contexts – but Hamad’s work sheds very useful light on what is at stake when conducting a textual analysis of sequences like this in the current climate.

Originally posted: 28 February 2017.

Updates:

12 February 2018: reinstated Marnie observation deleted from earlier draft, placing it in brackets and amending the text either side of this comment to incorporate it.

28 February 2023: to fix two dead links, removed one link entirely and replaced another with the address that had been changed by the site hosting that piece.

21 February 2025: two minor amendments to individual words for clarity.

Call the Midwife series two episode five, tx. 17 February 2013. ↩

David Bordwell, Kristin Thompson and Jeff Smith, Film Art: An Introduction Eleventh edition (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2017), p. 244. This essay uses this definition because this book is the most often-cited source on technique, though the essay is mindful of risks in doing this. Firstly, importing Film Studies approaches to television style risks denying the specificity of the televisual, which I have discussed extensively elsewhere and consider to be outwith the remit of this essay. Secondly, the use of the term ‘crosscutting’ may be more problematic: I am often mindful of the distinction between crosscutting and intercutting made in other sources, in particular Richard Barsam’s Looking at Movies: for example, although Bordwell and Thompson and others discuss a famous sequence of misdirection from The Silence of the Lambs as an example of crosscutting, following Barsam’s distinction the sequence would be more accurately described as intercutting whose defining strategy of misdirection depends upon it being misunderstood as crosscutting. ↩

Call the Midwife series six episode six, wr. Louise Ironside, pr. Ann Tricklebank, exec. pr. Pippa Harris, Heidi Thomas, dr. Lisa Clark, tx. BBC One, 26 February 2017. ↩

As Faye Woods rightly pointed out in response to the analysis of archive montages in the This is England series during David Rolinson and Faye Woods, ‘Is This England ’86 and ’88? Memory, haunting and return through television seriality’, in Martin Fradley, Sarah Godfrey and Melanie Williams (editors), Shane Meadows: Critical Essays (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2013). ↩

Lucy Fife Donaldson, ‘Repeating and rearticulating space: Inspector Morse’s house’, CST Online, 6 June 2014, available here. The quotation is a summary of Billy Smart, ‘The case of Juliet Bravo: You have to watch all of a series to truly understand a series’, CST Online, 18 October 2012, available here. The article mentions Amy Holdsworth, Television, Memory and Nostalgia (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011). ↩

Compare, for example, one of the many associative cuts in the film Don’t Look Now, as we move between mother and daughter, in different locations, mirroring hand gestures in front of mouths. ↩

See for instance the logic through which telephone conversations are filmed or the sequence in The Special Relationship in which Hillary Clinton has a shot/reverse-shot conversation with a television interviewer which extends to a virtual conversation with the watching Tony Blair and team and, most pressingly, Bill Clinton. ↩

I develop this observation in a comparison between Bresson and Alan Clarke in my book Alan Clarke (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2005). ↩

Hannah Hamad, ‘Contemporary medial television and crisis in the NHS’, Critical Studies in Television, Volume 11, Number 2, 2016, p. 142. This line includes quotations from Angela Henderson, ‘Emotional labour and nursing: An under-appreciated aspect of caring work’, Nursing Inquiry, Volume 8, Number 2, 2001, and Arlie Hochschild, The Managed Heart: Commercialization of Human Feeling (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1983). ↩

Hamad, pp. 142-143. ↩

Estella Tincknell, ‘Dowagers, Debs, Nuns and Babies: The Politics of Nostalgia and the Older Woman in the British Sunday Night Television Serial’, Journal of British Cinema and Television, Volume 10, Number 4, 2013, p. 773. ↩

Ibid., pp. 781, 770. ↩

Hamad, p. 145, quoting Julia Hallam, Nursing the Image: Media, Culture and Professional Identity (London and New York: Routledge, 2000), p. 34. ↩

The comparison with Lenin’s NEP is developed in Graham Roberts, The Man With The Movie Camera (London: I. B. Tauris, 2000). ↩

Tincknell, p. 775. ↩

Lez Cooke, ‘The new social realism of Clocking Off, in Jonathan Bignell and Stephen Lacey (editors), Popular Television Drama: Critical Perspectives (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2005), p. 178. As discussed in Dave Rolinson, ‘Small screens and big voices: Televisual social realism and the popular’, in David Tucker (editor), Social Realism in the Arts since 1940 (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011), which was sadly written before Call the Midwife started. ↩

Cameraman: The Life and Work of Jack Cardiff (2010), dr. Craig McCall. ↩

Hamad, p. 146. ↩