DAVID ROLINSON

Play for Today Writer: Dennis Potter; Director: Alan Bridges; Producer: Graeme McDonald

“I had to turn my back on all that I had been brought up to love…”

Western journalists visit Moscow to interview Adrian Harris (John Le Mesurier), a former controller in British intelligence who was also a Soviet agent passing on vital information, and who has now defected. Harris believes in both Communism and Englishness – he believes that he has betrayed “my class, yes… my country, no” – but the press find these beliefs incompatible, and want to find out why he became a “traitor”. Harris is plagued by anxieties over his actions and his upper-class childhood, and drinks to a state of collapse. Describing Traitor by using a synopsis gives the misleading impression that the play has a straightforward attitude to Harris’s psychology, just as its staging can be too easily seen as conventional – apart from a few filmed scenes and flashbacks, much of the play is based around dialogue-heavy confrontation on one set, which led some reviewers to find it “heavy going”, a “static and verbose” piece “long on self-conscious speeches and dialogue tussles which depended for their effectiveness upon liberal use of literary quotations”.1 It is no surprise that it was later remade for radio.2 However, Traitor is one of the most thematically ambitious of Dennis Potter’s early plays, tackling family psychology, patriotism and, through nuanced use of literary quotation, the way culture and institutions reinforce political values.

Potter achieves this through his personal interpretation of the biographical details of Kim Philby. Inevitably, some critics prioritised Philby in their responses. A Sunday Times preview argued that a documentary made a year earlier, with the cooperation of Philby’s son, “was not very illuminating” because “it clearly needed the insight of a novelist or playwright to probe the motives and motivations of betrayal to make this shadowy Graham Greene figure come alive”, but though Potter’s fictionalisation gave him “the dramatist’s escape”, the previewer felt that this was “a pity” because “it would have been more exacting to have called a spade a spade and a Philby a Philby.”3 Potter denied making it “entirely Philby” as this involved “a sphere of writing that I am… not interested in”4. It is also, as the makers of the Philby-Burgess-Maclean-Blunt serial Cambridge Spies found out, a sphere of writing open to criticism for factual inaccuracies.5 Critics’ emphasis on biography was a variation on their increasing emphasis on Potter’s autobiographical input – an urge that Potter understood in terms of how “When the novelist says ‘I’ you know he doesn’t mean I, and yet you want him to mean I”.6

Philby may be just a motor for Potter’s art, but there is more of Philby in Harris than just a shared stutter.7 For instance, there is his name: Kim’s real name was Harold Adrian Russell Philby, and it is a short journey from “Harold Adrian” to “Adrian Harris”. Then there is his background – affluent family, public school, Oxbridge, and conversion to Communism during the hunger marches when Philby (like Harris) realised that “the rich had had it too damned good for [too] damned long and the poor had had it too damned bad and that it was time it was changed”.8 Adrian suffers in comparison with his archaeologist father Arthur; Philby’s father, G Kitson Clark, was a polymath who published on subjects including archaeology, and overshadowed Kim at school literally (at one stage giving a lecture there) just as Arthur figuratively overshadows Adrian. Kitson Clark also publicly attacked Britain’s moral decline.9 A flashback sequence showing Harris scheming in the murder of a Russian defector is similar to Philby’s role in the Konstantin Volkov affair, placing Traitor in the same area as Philby, Burgess and Maclean, the highly successful ITV Playhouse drama documentary written by Ian Curteis.10

Why does Harris ‘betray’ Britain? On one level, this could be read simply in terms of his psychological weakness. Trading on common perceptions of Philby’s decline, the play resembles his “period of doubt and disillusionment” in the Soviet Union, during which “whisky was his only solace”.11 On 17 December 1967, the Sunday Times published the only interview that the British press conducted with Philby after his defection (until the late 1980s). It’s worth comparing the opening scenes of Traitor, in which Harris nervously waits with a bottle as the journalists arrive, with this piece by Murray Sayle:

The room was completely bare except for two chairs and a table on which stood a briefcase, a bottle of vodka and two glasses. The table stood by the window with a breath-taking view over Moscow… [Philby] is a courteous man, smiles a great deal, and his well-cut grey hair and ruddy complexion suggest vitality and enjoyment of life… He is clearly a sociable type of drinker and he seems to have an iron head; I could detect no change in his alertness or joviality as the waiters arrived with relays of 300 grammes of vodka or 600 grammes of brandy.12

Though Traitor captures the kind of drinking that Philby clearly indulged in while in Moscow, Philby was less likely than Harris to have got so drunk that he sprawls on the floor. Of course, had Harris entertained these journalists in restaurants, much of the play’s claustrophobia would have been lost. Harris’s room contains a landscape portrait, a metaphor for the England on which Harris has (according to that week’s Radio Times cover, which was devoted to Traitor) turned his back. Frederick Forsyth claimed that Philby was “profoundly nostalgic for Old England – he has every magazine and newspaper and cannot wait to do The Times crossword… to keep abreast of things going on in Britain he’ll even go into a bar in Moscow just to sit and listen to British businessmen’s conversations”.13 “Old England” is similarly vital to Harris, but his Englishness cannot be summed up in terms of The Times crossword. Potter stressed that he was interested in “the misstatement that someone could politically betray their country and be presumed not to love it”. Away from concepts like “nationalism” and “militarism”, “something” is left to which “you emotionally respond, in the same way as you acknowledge your own parents”.14 This is the pull felt by Harris – a somethingness very much related to his parents.

The interview is interspersed with subjective flashbacks, to Harris’s father, his humiliation at school, and the murder of the Russian defector. The latter image comes as a shocking sudden red flash of blood; for this reason, it’s no surprise that Potter went on to work with the director Nicolas Roeg, a master of colour and associative editing. As Humphrey Carpenter put it, Potter “developed the device of subliminally swift and repeated flashbacks or cutaways to suggest what is passing through a character’s mind”.15 Passing through Harris’s mind are memories which offer biographical explanations for his later treachery. Rather than accepting his deep intellectual conviction, the journalists “put it down to some kind of sickness”, but Harris’s protests against this are weakened by the insistence with which the play reinforces those motivations. His rant against “the festering hypocrisies of the English ruling families” is made to seem juvenile by an overdubbing of his voice as a child complaining about public school: “I hate it here”. As in Stand Up, Nigel Barton, there is a pivotal flashback to a childhood humiliation in school – his teacher bullies him for his stuttering recital of Blake16 After an insolent reply, the young Adrian is slapped across the face, an act of officially sanctioned brutality from which Alan Bridges cuts to images of police action against the Jarrow marchers and scenes of poverty, set to Jerusalem , an ironic device contrasting “England’s green and pleasant land” with violence which was performed with stunning effect by Tony Richardson in The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Runner (1962).

Although Harris denies James’s argument that the child is father to the man, the play supports it. His father was obsessed with his namesake, King Arthur, and Camelot, embedding in him – as John Cook put it – a “dream of perfection which leads him in adulthood to embrace extreme political ideologies that seem to offer a similar panacea to all the world’s problems”.17 Our privileged knowledge of Harris’s father through flashbacks gives us a sense of superiority; despite his denials, we see his father’s influence through echoed dialogue. After his father had told him that most people “are like those pigs down there. They runt about, pushing their snouts in the mud, never dreaming that there are better things over the pigsty wall”, the present-day Harris accuses the journalists of “runting about like a porker”. Or the landscape picture – a smaller version of one overlooking his father’s dining table, at which Sir Arthur bemoans the unemployed for judging men by “pounds, shillings and pence” while he’s brought food on a silver platter. Three times we flash back to Arthur reading his son this passage from Tennyson’s Morte d’Arthur:

And slowly answered Arthur from the barge:

‘The old order changeth, yielding place to new,[…]

If thou shouldst never see my face again,

Pray for my soul. More things are wrought by prayer

Than this world dreams of. Wherefore, let thy voice

Rise like a fountain for me night and day […]

But now farewell. I am going a long way

With these thou seest – if indeed I go –

(For all my mind is clouded with a doubt)

To the island-valley of Avilion;

Where falls not hail, or rain, or any snow,

Nor ever wind blows loudly; but it lies

Deep-meadowed, happy, fair with orchard-lawns

And bowery hollows crowned with summer sea,

Where I will heal me of my grievous wound.’18

This passage is vital to the play. The young Adrian is unsettled, and screams – his father doesn’t get beyond “Deep-meadowed” until the end credits (when this final destination at which “I will heal me of my grevious wound” is spoken over images of the Soviet Union). Though noting this dream of perfection, the play explores the idea that “all my mind is clouded with a doubt”. This could simply be Harris’s doubt in Communism, reinforcing Potter’s belief that “the worst traitors are the dogmatists who think it is weakness to change their minds”.19 But could this not also be applied to the patriotic figures in the play? As Potter said of Tennyson in a later interview, “To us perhaps it is the quality of the doubt which catches hold”.20 There’s no room for doubt in the young Adrian’s world, and poetry itself reinforces the brutalising, divisive system. The above passage – Adrian’s father’s idea of light bedtime reading! – is spoken to Sir Bedivere, whom King Arthur attacks elsewhere as “miserable and unkind, untrue,/Unknightly, traitor-hearted!”, for having “betrayed thy nature and thy name,/Not rendering true answer”.21 Perhaps Adrian screams because his father makes his understandable unhappiness seem like inevitable treachery. Here Englishness is reinforced by culture, as this treachery is put in the words of Tennyson, a Poet Laureate with the weight of high culture behind him. This weight is behind the teacher’s slap when Adrian “counterfeits” William Blake. This is the upper-class England which Harris doubts, reinforced by culture, but “There is another England, you know, and you can paint it in blood and tears and sweat and slime and shit!” He recalls:

My father was an archaeologist… spent most of his time digging below the top-soil, trying to find some remnants of Camelot. Well, I prefer to dig below a different sort of top-soil, not to find out about some mythical past, but to try and lay bare the reality of class conflict, to see it for what it is, and thus to see the machinery of change and growth, of renewal.

Blake is an interesting choice for such a pivotal scene. He is vital among the play’s many literary quotations, indeed the play is bookended with Harris talking himself through ‘Love’s Secret’ – “I told her all my heart–shit!” This radical had his words for Jerusalem set to a culturally-reinforcing paean to England. So, Potter’s use of quotation connects Harris’s dilemmas not only with national identity, but also with literary radicalism. Potter’s choices are impeccable, and self-aware – perhaps he is also questioning his own radicalism. To argue that any plays are ‘really about Potter’ is problematic, given that his use of the surface elements of autobiography is knowingly unstable, but the way in which critics of the time made that connection says a lot about the nature and scope of his profile: Nancy Banks-Smith, for instance, called Traitor “passionately personal” as his childhood was “always the father, the school and the child”, and drew comparisons between this play and Stand Up, Nigel Barton since “nothing in […] Traitor bleeds quite so freely as the scene with the child and the sarcastic sadist schoolmaster.”22 Later, John Cook also compared Traitor with Stand Up, Nigel Barton, featuring a character “uprooted from and betraying his original social class”.23 Caroline Seebohm told Humphrey Carpenter that Potter’s friends “thought he’d sold out… a traitor to his class”, leaving Potter “in conflict about himself”.24 This matches the quotations – Harris sneers at a quotation from Wordsworth, who moved ideological positions from welcoming the French Revolution to apparent fascism. “There was a time”, Harris tells his questioners, “when poets exploded like bombs. Now the same word-mongers don’t even explode like punctured bags of stale air… They’ve forgotten passion”. He’s quoting Auden, whose words were a call-to-arms for those who’d fight the ideological fight in the Spanish Civil War. Some critics felt Potter was being too clever by half. Perhaps admonishing himself, Potter gives Harris a choice insult for James: “Literate, aren’t you? Must be a hell of a problem for you when you’re cabling your stories… a few sordid little paragraphs… between the tit and thigh”.25

However, I like to think that this cleverness might be down to Harris. Looking back through those quotations, each reflect the present-day Harris – is his memory coloured by his present predicament, or is he just making up stories, “Not rendering true answer”? When the journalist James (any relation to Henry James?) talks about the child being father to the man, he may be referencing Wordsworth or Gerard Manley Hopkins’s poem of that title which offers an interpretation of Wordsworth’s point. Adrian Harris dismisses the journalists’ names (and he has a point: as well as James there is a Thomas and a Blake, all solid literary names) because they “could be called Nelly Dean for all I care”. A drinking song reference, or a reference to the character from Wuthering Heights, one of English literature’s most notorious unreliable narrators? At the end, we suddenly flashback to the beginning, Harris awaiting the journalists. This time, however, we see him discover a KGB microphone, and tell himself “Remember the microphones and be careful… For God’s sake remember the microphone!” Is this a straightforward flashback (he knew he was bugged at the start and has just put on an act) or have we spent the duration of the play in Harris’s mind (the journalists haven’t arrived yet, and he’s imagining what happens next)? The second explanation is supported by the subjective structure, an earlier cutaway to Harris’s face which didn’t match the scene it was in, or his description of “home” as “a journey you take inside your head”. Either way, he’s lying to someone – the journalists, the KGB, or himself – and, in the tradition of the poets, telling stories. The distinction between telling stories and telling lies is an important point in Potter’s fiction and non-fiction, and had been central to Lay Down Your Arms.

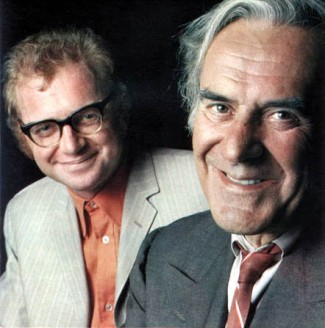

Traitor is a gripping, claustrophobic piece built around a tour-de-force performance from John Le Mesurier. He was familiar for comedic roles as upper class eccentrics, and was becoming particularly famous for his part in Dad’s Army, so his casting might look like a brave move. It wasn’t out of character for Potter: in response to Roy Hudd’s importance to Potter’s late pieces, W. Stephen Gilbert noted that “all his life Potter wanted comedy specialists in his work, sometimes getting them (Stanley Baxter, John Le Mesurier, Bill Maynard, John Bird, Lionel Jeffries, Dave King) but frequently failing to do so (he wanted Tony Hancock to play Jack Hay […in Vote, Vote, Vote for Nigel Barton], Hudd, Penelope Keith and Spike Milligan to lead Pennies from Heaven, Max Wall and Jimmy Jewel for Blade on the Feather)”.26 The person most surprised by the casting appeared to be Le Mesurier himself. He showed the script to Dad’s Army co-stars, saying “I don’t know whether I should do this”,27 and, according to his family, worried about the amount of work required on such “long, ranting speeches” for such a potentially ephemeral broadcast, in response to which he was told “this is hard work” unlike “rais[ing] your eyebrows in light comedy”.28 Reviewers expressed similar sentiments in their unanimous praise for his performance: Nancy Banks-Smith wrote that the part of Harris “was a formidable aria” for Le Mesurier: “Cursed with so Hamlet-like a face, he seems to have been coerced into comedy. This, his Hamlet, was worth waiting for.”29 The doubts had run more deeply: his family recalled that “he was very, very scared” that “he wouldn’t be able to pull it off”.30 Le Mesurier went on to win the BAFTA Award for Best TV Actor. His wife recalled that “he didn’t believe in prizes… he used to keep the bedroom door propped open with it”.31 That was an act of which Adrian Harris might have approved.

Originally posted: 1 July 2003 on the old Mausoleum Club version of this site.

Updates:

2006: transferred to the old University of Hull version of this site.

2009: transferred to new Play for Today mini-site initially separate from the British Television Drama site

4 November 2010: first appearance of this essay on the main British Television Drama site, moved from a different URL, as all the pieces from the old mini-site were transferred to the main site.

15 December 2014: added Sunday Times “was not very illuminating” quotation; amended accompanying paragraph; some rewording; extra comments on Blake and Paper Roses; minor typographical corrections.

21 December 2014: added Banks-Smith quotations and amended accompanying text; added “It wasn’t out of character” sentence with Gilbert quotation and amended accompanying text; added two images from It’s All Been Rather Lovely: one from Traitor and one from the British Screen Awards.

5 February 2017: added images; added link to Loach DVD set; minor typographical corrections mostly involving the placement of punctuation around endnote markers.

4 March 2017: standardised presentation of ‘Updates’ legacy information (2003, 2006, 2009) in line with current site practice; removed ‘(first published: 2003)’ from byline as a result; deleted one word from final sentence.

Pingback: Play for Today: Traitor – Forgotten Television Drama