by OLIVER WAKE

Writers: Clive Exton, Leon Griffiths, Leo Lehman, Terry Nation, Julian Bond, Bruce Stewart, Richard Waring, Denis Butler; Adapted from: John Wyndham, Rog Philips, Isaac Asimov, Tom Godwin, Philip K Dick, Robert Moore Williams, Katherine Maclean, Raymond F. Jones, Frank Crisp, Clifford D Simak, Arthur Sellings; Directors: Charles Jarrott, Jonathan Alwyn, Douglas James, Paul Bernard, Peter Hammond, Guy Verney, Richmond Harding, John Knight, Don Leaver, John Knight, Alan Cooke

There are many reasons why a television series may languish in obscurity, perhaps primarily because it simply does not merit any interest. However, this is not the case with ABC’s 1962 series Out of This World – British television’s first science fiction anthology – which suffers obscurity due to two factors independent of the programme itself. Only one episode exists in full, leaving little scope for re-evaluation, and the series has long been overshadowed by its celebrated longer-running BBC cousin Out of the Unknown. However, Out of This World is not just worthy of attention as a curiosity, but as an original and successful series in its own right.

By 1962, ABC was already the most prolific of the ITV companies in the production of science fiction. In 1960-61 they had produced Malcolm Hulke and Eric Paice’s children’s serial Target Luna and its three Pathfinders (in Space, to Mars, to Venus) sequels. Several juvenile science fiction adventures in the same mould, such as City… and Secret Beneath the Sea, followed over the next few years. ABC also made adult science fiction, with its prestigious drama anthology Armchair Theatre producing a number of examples of the genre, both original teleplays and adaptations of on pre-existing works. The former, such as I Can Destroy the Sun (1958) and The Man Out There (1961), were the more interesting, often being inspired by contemporary subjects such as Cold War tensions or the space race, as in these cases. Clearly both the resources and, more importantly, the inclination, for adult science fiction were present at ABC, but never had they come together to form a regular series.

The initial idea for Out of This World came in 1961 from Irene Shubik, a story editor on Armchair Theatre. She presented her concept for an anthology of science fiction plays to ABC drama supervisor Sydney Newman. In her 1975 memoir, Shubik recalled that “Science fiction of the ‘adult’, as opposed to the ‘bug-eyed monster’, kind had always been a pet subject of mine”. Shubik believed that science fiction was responsible for some of “the most original and philosophical ideas to be found in fiction writing today.”1 She wanted to present stories that weren’t mere pulp fiction but satirical and relevant to contemporary life. Newman (who himself had a strong aversion to bug-eyed monsters – or ‘BEMs’ – in science fiction) was won over by the potential of the series. “Having given me the go-ahead,” Shubik wrote, “I believe he began to worry that I would come up with a collection of metaphysical works by authors like Karel Capek, instead of ‘a popular adventure TV series’.” Newman promptly assigned Shubik an assistant from the ABC accounts department who was a life-long science fiction fan. “Shubik’s bug-eyed monster”, as he became known, was to be a watchdog to ensure that the story editor didn’t deviate too far from popular taste.2

When it came to choosing material for the series, Shubik had not only her ‘bug-eyed monster’ for assistance but the good will of other experts in the field, such as Edward John Carnell. As John Carnell, he was the editor of the New Worlds science fiction magazine, and a luminary of the fantasy fiction fraternity. His co-operation, suggestions and extensive list of contacts were invaluable, and New Worlds would later promote Out of This World on the cover of its July 1962 issue.

When it came to choosing material for the series, Shubik had not only her ‘bug-eyed monster’ for assistance but the good will of other experts in the field, such as Edward John Carnell. As John Carnell, he was the editor of the New Worlds science fiction magazine, and a luminary of the fantasy fiction fraternity. His co-operation, suggestions and extensive list of contacts were invaluable, and New Worlds would later promote Out of This World on the cover of its July 1962 issue.

The series’ first challenge was in finding enough suitable stories to dramatise. In a preview article in his magazine, Carnell explained how this problem had stymied several earlier attempts at similar series. He expanded:

Science fiction material is a difficult medium to put before cameras and even more restricted when applying the close-up technique required by television. Discounting the thousands of short stories requiring impossible settings and improbable alien monsters, telepathy, galactic backgrounds and major scientific equipment not yet invented let alone designed and built (and it is surprising how many there are when you think in terms of visual presentation), suitable short stories seldom have sufficient plot material in them to make a one-hour play, while novels have too much. The list of ‘possibles’ is rapidly (if somewhat laboriously) reduced, leaving mainly novelettes and a handful of short stories with a good plot line but requiring additional sub-plot material to sustain the interest and drama.3

Faced with this problem, Shubik needed to be able to rely on her assembled writers to turn the chosen stories into fully-rounded television plays. Shubik was glad to discover that several top television dramatists were also science fiction aficionados. She was able to engage Clive Exton, who had made his name with ground-breaking Armchair Theatre scripts, to adapt stories for the series. Only too late did she discover that David Mercer, perhaps the most famous television writer in 1962, would also have been willing to lend his talents to the anthology. Carnell also noted the necessity of avoiding the duplication of any one of science fiction’s sub-genres (eg, robots or time travel) within a series.4 It’s notable how well Out of This World manages in this respect, comprising a set of stories diverse not just in their science fiction aspects but also in their wider dramatic genres, including thrillers, mysteries, comedies, suspense stories, etc. “Drama and suspense in credible science fiction settings are keynotes of the new series”, Carnell had reported.5

The series found a producer in the form of Leonard White, who had previously been responsible for Armchair Mystery Theatre, a summer replacement for its parent programme, as well as the first series of The Avengers and episodes of Inside Story and Police Surgeon. The new series took the same format as Armchair Theatre: one hour plays broken into three ‘acts’ by commercials, and was recorded by the same technical crews at ABC’s Teddington studios.

John Wyndham’s 1952 short story Dumb Martian was chosen to begin the series in June 1962. In the cautionary morality tale, dramatised by Clive Exton, a boorish spaceman purchases an apparently unintelligent Martian girl to be his ‘wife’ on a five-year assignment to a remote space station. However, after suffering much abuse, she proves not to be so ‘dumb’ and turns the tables on her ‘husband’. Dumb Martian was not ultimately transmitted as an Out of This World production, with Newman shrewdly poaching the play for Armchair Theatre as a teaser for the science fiction series which then started the following week.6

Boris Karloff appeared at the conclusion of Dumb Martian as the dinner-suited host inviting viewers to tune in to the new show. In this role, Karloff would introduce each episode of Out of This World, and sometimes trail the next week’s play at an episode’s conclusion. It was an American practice, used to maintain an element of continuity across the otherwise unlinked plays of an anthology series, which White had previously employed on Armchair Mystery Theatre, with Donald Pleasence hosting. White felt the 75 year old Karloff brought an appropriate “touch of ‘other worldliness’.”7

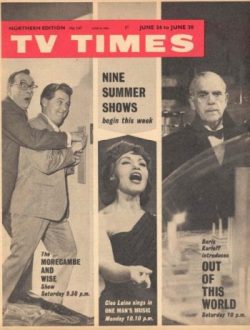

Karloff also wrote a short introductory article for each play in the commercial television listings magazine TV Times. Wyndham himself wrote an article about the science fiction genre in the TV Times for the week the series debuted.8 The same issue splashed the series on its cover, with a third of the page comprising a photograph of Karloff on the set of the upcoming episode Impostor.

Karloff also wrote a short introductory article for each play in the commercial television listings magazine TV Times. Wyndham himself wrote an article about the science fiction genre in the TV Times for the week the series debuted.8 The same issue splashed the series on its cover, with a third of the page comprising a photograph of Karloff on the set of the upcoming episode Impostor.

The series got off to a fine start at ten o’clock on Saturday 30 June with The Yellow Pill, based on a story by Rog Philips. The play tackled the thorny issues of reality and delusion. Under interrogation by a psychiatrist, an alleged murderer claims to be onboard a spaceship thirty years in the future, in which the doctor is his shipmate. The doctor urges him to take a yellow pill which will help him throw off the hallucination. But is he really mad or is there substance to his apparently lunatic ravings? Inevitably, it’s the latter, as the doctor eventually discovers when he takes the pill himself and finds himself back onboard ship. The play took eleventh place in the week’s ratings, being watched in around 4.6 million homes, which White equated to eleven million viewers.9

Little Lost Robot, dramatised by Leon Griffiths from an Isaac Asimov story, is the only episode of the series that still exists, though it too was originally thought to have been lost. The telerecording was rediscovered in 1991 by TV enthusiast group Kaleidoscope at the Pinewood film store of Lumiere, who had taken possession of ABC’s archive. The play opens with the standard title sequence, a time-lapse montage of what might be microscopic organisms or plants twitching, growing and surging. It isn’t clear exactly what they are and this ambiguity, coupled with the plonking piano and drum music, makes for an eerie opening.

Then the plummy Karloff introduces us to Hyper-Base 7, a research facility in the vicinity of Saturn. There, in a moment of anger, Mr Black (played by ex-Pathfinder Gerald Flood) orders a comically lumbering petrol-pump-like robot to “get lost”. It does this in the most effective way it can, by hiding itself amongst twenty other identical robots. They are “Nestors”, highly advanced and very expensive. However, this one robot has a modified First Law, meaning that while it still should not hurt a human, it may not always take steps to prevent one from coming to harm. A small difference, but a potentially deadly one. If the robot is not found, all twenty-one must be destroyed, at great expense. Icy robot psychologist, and regular Asimov character, Dr Susan Calvin is called in to help.

Finally identified in the third act after a variety of tests, the ‘lost’ robot goes berserk and kills Black before being fried with gamma-rays. “I lured him to his death,” weeps Calvin, referring to the robot. Nobody seems terribly bothered about Black. Calvin’s aide ponders: “Twenty robots… whirling through the universe with a sense of evil. Is this what we have achieved?” Then Karloff leads into the credits with a suave: “and now for tonight’s cast.”

Asimov’s original story is much embellished by dramatist Leo Lehman, who fleshes out the characters with details such as station commander Kellner’s hobby of rose growing. However, he also has a penchant for melodramatic dialogue, and inserts the (entirely inappropriate, within the play’s own narrative logic) killing of Black to spice up the quieter ending of the original story. Little Lost Robot was the first of two instalments to be directed by Guy Verney, who had previously directed the Pathfinders serials.

Clive Exton’s first script for Out of This World proper was Cold Equations, from the story by Tom Godwin. It starred Jane Asher and Peter Wyngarde in what was nearly a two-hander about a girl who, hoping to see her brother, stows away on a rocket rushing a life-saving serum to a frontier world. However, the rocket has only enough fuel for the calculated payload, and either the pilot must put her out into space to die or the rocket will crash. It was a gloomy play with the inevitability of Asher’s eventual expulsion into space being clear from very early on. Although the episode as a whole is lost, an off-air soundtrack recording does exist and is included on the series’ 2014 DVD release.10

Credit: BFI National Archives provided us with this ABC image from Impostor in accordance with ABC copyright wishes.

Philip K Dick’s Impostor was the next short-story for dramatisation. It is set in a future where humanity lives under a vast protective dome due to the continuing nuclear war with the “Outspacers”. The humans hope to end the war with the imminent firing of a new super-weapon. Then, weapons scientist Roger Carter is suddenly accused of being an impostor, a robot bomb sent by the enemy. He goes on the run, but how can he prove his innocence when surely the robot impostor would be programmed not to know that he is an impostor? When he discovers the body of the real Carter, his realisation that he is indeed the impostor detonates the bomb.

Credit: BFI National Archives provided us with this ABC image from Impostor in accordance with ABC copyright wishes.

It is a fascinating story, including all the themes of identity and authenticity that preoccupy the writer, within a gripping thriller plot. However, one contemporary review suggests the episode was not wholly successful. Tony Gruner wrote in Kinematograph Weekly that it “possessed a lot of movement and a fair amount of scenes, [but] budgetary limitations in sets was painfully apparent, thus spoiling the potential appeal of a good play.”11 Nevertheless, it remains notable as the first Philip K Dick adaptation to have been produced for television or film and it is sad that it now exists as a soundtrack recording only, with around eight minutes missing (this recording can also be found on the DVD). The story’s dramatist, Terry Nation, would make his fortune over the next few years writing science fiction for the BBC’s Doctor Who12 and his scripts for the series betray the lasting influence of Impostor.

Immigrant, about the mysterious paradise planet Kimon, from which no one returns, was another Nation adaptation later in the series, this time from a Clifford D Simak story. More importantly, Nation also wrote the first of only two original scripts presented by the series. Botany Bay was a horrific tale with some effective plot twists and direction. The Times’s ‘Special Correspondent’ noted that the play was “Particularly disturbing”, reporting how Guy Verney’s direction derived “the maximum effect from keeping us – literally as well as metaphorically – very much in the dark.” Set in a sinister psychiatric institute, the story concerned aliens transferring their minds into those of the inmates.

The final twist reveals that the story is not in fact set on Earth after all. The Special Correspondent found it as gloomy as previous episodes, “doubly so, in fact, since not only did we see intelligences – apparently evil intelligences – from another planet triumphing over ordinary people like you and me, but worse, by an ingenious twist at the end we were made to realise that we ourselves, the inhabitants of earth, were the sinister intruders on some simpler future world: that not only were the wrong ‘uns winning, but they were us after some further centuries of decadence.”13 As an original and intriguing teleplay in a series largely comprised of adaptations it is particularly sad that no recording of this instalment survives.

Letters to the TV Times suggested the reception of the first few instalments of the series had been mixed. One viewer congratulated the series on being “the first serious science-fiction ever to be seen on British TV” and suggested it could run for 20 years. However, another was less impressed, opining: “It’s bad enough having to watch the trash in this world without having to watch Out of This World.”14 Nevertheless, despite an almost inevitable reduction in audience numbers after the initial episode, ratings remained reasonable, with both Little Lost Robot and Cold Equations being the nineteenth most watched programmes of their respective weeks, with a little over 3.4 million homes tuning in to each.15 Ratings are unknown for most of the later episodes, meaning they likely dropped out of the top twenty programmes for their weeks.16

Another letter to the TV Times asked: “Why is it that the writers of Science Fiction always write of horrors?” She continued:

Is it inconceivable that other worlds should be even more beautiful than this, or that the inhabitants of these worlds should regard us with feelings of generosity, kindness and friendship or that we could reciprocate these feelings? […] Please let us, just for once, have a story with a warmth of good feeling as a basis, instead of mistrust and destruction.17

Sadly, such good feeling rarely makes for compelling drama, but her wish was almost immediately answered with the episode Medicine Show. In Robert Moore Williams’ story, dramatised by Julian Bond, two strange doctors arrive in a small American town with a machine that provides miracle cures, and they ask only for seeds in payment for their service. Inevitably, they have otherworldly origins. It had a strange effect upon some of its audience, with Shubik recalling later that she received many letters from those wanting to take advantage of the extraterrestrial medicine men’s services.18 “Quite an enjoyable hour of space mysticism”, was the verdict of The Stage and Television Today.19 Echoing the earlier correspondent, another TV Times letter-writer commended the storyline, finding it “refreshing” that the aliens “came with a gift of healing and in friendship, instead of as creatures intent only on destruction and hatred.”20

Another play that stuck in Shubik’s mind was Pictures Don’t Lie, dramatised by Bruce Stewart from Katherine Maclean’s short story. After making first contact by radio, the arrival on Earth of an alien vessel is awaited. As they come in to land at the arranged spot, the aliens report over the radio that their ship is sinking into marshy ground and that they are besieged by hideous creatures. Scale is the issue, the great difference in size between human and alien unknown to each party. The spaceship is microscopic.

A more light-hearted episode followed. Vanishing Act was an original play by Richard Waring which starred Maurice Denham as the aspiring conjurer Edgar Brocklebank, who comes across the rather too effective vanishing cabinet of the late ‘Great Vorg’. Divided We Fall, dramatised by Leon Griffiths from a story by Raymond F Jones, was a serious tale reminiscent of the earlier Impostor, with its central dilemma revolving around the disputed existence of the synthetic people, the “Syns”. In 2033 the world’s greatest computer announces that the Syns are secretly working against humanity. But do the Syns, indistinguishable from humans, even exist? The Dark Star was dramatised by Denis Butler from Frank Crisp’s novel Ape of London and concerned a fatal disease which initially gives its carriers superhuman strength and seems to choose its victims for hierarchical progression through society.

Target Generation was another Clifford Simak tale and was dramatised by the prolific Clive Exton. It was the story of a spaceship that has travelled for centuries in its journey to another world. As generations of the crew have lived and died, knowledge about the ship and its mission has been lost. Can the young crew make sense of the instructions that have been left for them and recognise the signal of the end of their journey? The series concluded on a less serious, more satirical note, with The Tycoons, dramatised by Bruce Stewart from the story by Arthur Sellings. Three aliens on earth are preparing a weapon to control humanity. They operate under the cover of a business producing animated dolls created using their advanced technology. But as the front-business prospers, the aliens’ original mission is neglected.

Out of This World must largely be considered a critical success. Kinematograph Weekly’s Tony Gruner noted that, “Some critics of the series have noted its lack of physical action in some of the plays. For my money this has been all to the good […] those shows with a minimum amount of action came over well because the directors had sharper terms of reference and emphasised dramatically the intimate nature of the story.”21

This approach fitted well into the dominant mode of television drama at the time, which was particularly important given that ABC’s production resources didn’t run to the large-scale spectacle and elaborate special effects so beloved of Hollywood science fiction. However, conversely, it could be argued that the series lacked visual interest. To judge by the existing ‘tele-snaps’ (off-screen photographs taken by John Cura), much of the series offered little in the way of fantastical costumes or sets.22 On this score, the existing Little Lost Robot, with its space base and multitude of robots, may be the most extravagant, which could be an explanation for why it survived.23

The Yorkshire Evening Post was impressed with the series, preferring Out of This World to the BBC’s recent science fiction serials and admiring its “shape, form, lucidity and sheer ingenuity”. Their critic, H F Hall, felt it was “the most accomplished thing of its kind that TV has yet produced” and admired its “well-schemed scripting and disciplined production”.24 Writing after the transmission of Target Generation, the Daily Mail’s Peter Black noted that “The whole of this Out of This World series has been tremendously better than expectations of a Saturday night entertainment.”25

Meanwhile, Kinematograph Weekly thought the series “the most intelligent and best written of its genre since Quatermass” and praised White for “providing rich production values from what might appear to have been a limited budget”.26 Even the Times’ ‘Special Correspondent’, who had complained that the series was “not for the most part even superficially cheery”, had found it entertaining. Although asserting that the genre existed largely to chill and divert, like a Gothic novel, he felt that the programme’s “general level of writing and direction has been encouragingly high”.27 However, White’s favourite piece of feedback came from the comedian Michael Bentine in a telegram that read: “WONDERFUL SHOW OUT OF THIS WORLD PLEASE CONVEY JOYOUS CONGRATULATIONS FOR WONDERFUL ENTERTAINMENT AND KEEP SOME FOR YOURSELF”.28

Shubik’s contention that science fiction could, and should, have relevance to contemporary life and issues struck a chord with at least one critic. In the Sunday Times, Peter Laurie commended the series as an example of

what science fiction is good at: making us think about ourselves and our societies from the outside, making us realize that what we often assume is immutable is, in fact, only an adaptation to the very particular circumstances of our world. Soon, whether by technical development, or atomic war, or space travel, our civilisation is going to be faced with new problems on a vast scale. Science fiction is one way of preparing to deal with them.29

It seemed the experiment of producing a science fiction anthology for adults, tackling serious issues, had paid off.

Out of This World was a product of its age and it benefited from it. It aired as the nation began to burn with what Harold Wilson would call the “white heat” of the technological revolution a year later, but, crucially, as Shubik recalled, “before the moon landings made space seem not so far away after all.”30 Looking back in 2003, White recalled that the series was “a great pleasure to make, getting away from today and exploring the unrealities (or so we thought) of tomorrow. An opportunity for the suspension of disbelief even in the here-and-now ambience of television.”31

Despite its success, no second series followed. We don’t know why this was, but perhaps as a product of Sydney Newman’s leadership of the ABC drama department it may have suffered from his departure to join the BBC, taking effect at the beginning of 1963. This also resulted in White moving up to become producer of Armchair Theatre. The format, however, did not die. Shubik joined Newman at the BBC and, in 1965, with a rush of programming required for the new BBC2, the pair created Out of the Unknown. With Shubik now producing, the series took the same format as Out of This World, minus the Karloff host role. Out of the Unknown re-used dramatists (Terry Nation, Bruce Stewart, etc), sources (Asimov, Simak, etc) and even whole scripts (The Yellow Pill, Target Generation) from its predecessor. That series, however, is another story…

© Oliver Wake

With thanks to the BFI Reuben Library and Special Collections team, and Colin Cutler, for access to research material.

Originally posted: 2 December 2009.

[This piece first appeared in This Way Up issue 16 in 2005. It is presented here in revised and updated form.]

Updates:

27 August 2014: minor typographical corrections.

24 November 2014: added images from ‘Little Lost Robot’ via the DVD release.

22 February 2015: minor revisions and additions relating to the DVD release.

29 June 2018: substantial revisions: added new paragraphs and several new sentences in main body and endnotes, including coverage of pieces in the TV Times, Daily Mail and Kinematograph Weekly (all except the final quotation from Kinematograph Weekly are new), and more specific information on ratings, budgets, tele-snaps and a music composition; made minor revisions including standardising presentation of title Out of This World; added more names of adapting authors to main body of text and corrected Ape of London authorship; added two new images from Impostor courtesy of ABC and BFI National Archives.

1 July 2018: minor revisions; added New Worlds and TV Times images; amended endnotes in relation to those images and amended paragraphing to accommodate them.

28 April 2022: added substantial coverage of, and quotations from, Carnell piece; minor deletions and revisions such as splitting a paragraph to accommodate new material; additional acknowledgement.

29 April 2022: amended one letter typo in Carnell quotation.

Out of this World was released on DVD by the BFI on 24 November 2014, containing ‘Little Lost Robot’ plus audio recordings of ‘Cold Equations’ and ‘Impostor’ and a downloadable PDF of the script for ‘Dumb Martian’. Oliver Wake contributed an essay to the accompanying booklet.

Irene Shubik, Play for Today: The Evolution of Television Drama Second Edition (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2000), p. 36. ↩

Ibid, p. xiii. ↩

John Carnell, ‘ABC Television’s Out Of This World’, New Worlds, vol. 40 no. 120 (July 1962), p. 126. ↩

Ibid., p. 127. ↩

Ibid., p. 125. ↩

White confirms Dumb Martian was originally intended for Out of This World in his fascinating memoir: Leonard White, Armchair Theatre: The Lost Years (Tiverton: Kelly Publications, 2003), p. 72. ↩

Ibid. ↩

John Wyndham, ‘Science Fiction: The Facts’, TV Times, number 347, 22 June 1962, p. 11.

The whole issue can be viewed online here . ↩Ratings are taken from cuttings found in Leonard White’s Out of This World scrapbook, now held by the British Film Institute. White’s estimate of 11 million viewers is given in White, Armchair Theatre, p. 72. ↩

Out of This World, British Film Institute, BFIV2021. ↩

Tony Gruner, Kinematograph Weekly (further details currently unknown – cutting accessed via Leonard White’s Out of This World scrapbook). ↩

Nation invented the Daleks, who made their first appearance in the series’ fifth episode, first broadcast on 21 December 1963. For the influence of Impostor on Nation’s Doctor Who scripts, see Wake, Oliver, ‘Impostor’ in The Essential Doctor Who: Adventures in the Future, a Doctor Who Magazine ‘bookazine’ from Panini UK Ltd published June 2018. ↩

Anonymous, ‘Not Taking It Easy This Summer’, The Times, 4 August 1962, p. 10. ↩

Letters from, respectively, Robert Yarwood and Helen Womack subtitled ‘Science ahead’ in ‘Viewerpoint’, TV Times number 353, 3 August 1962, p. 3. ↩

Ratings are taken from cuttings found in Leonard White’s Out of This World scrapbook. ↩

The exception is Vanishing Act, which was rated eighteenth most watched programme for its week, with a little under 3.7 million homes viewing. Ibid. ↩

Letter from Phyllis M Sharpe subtitled ‘Kindness in space’ in ‘Viewerpoint’, TV Times number 355, 17 August 1962, p. 2. ↩

Shubik, Play for Today: the evolution of television drama, p. 38. ↩

Anonymous, ‘ABC’s science fiction series provides… An enjoyable hour of space mysticism’, The Stage and Television Today, 9 August 1962, p. 9. ↩

Letter from Julia Wakefield subtitled ‘Space gifts’ in ‘Viewerpoint’, TV Times number 356, 24 August 1962, p. 3. ↩

Gruner, Kinematograph Weekly. ↩

John Cura took a series of tele-snaps for every episode of Out of This World. Leonard White preserved these in his Out of This World scrapbook. ↩

We don’t know why Little Lost Robot alone survived in the archive, but it’s not unknown for a single episode (or small handful of episodes) of a series to be retained as an example of the series by a television company ‘junking’ old programmes. If that were the case here, Little Lost Robot’s obvious science fiction iconography could have been the reason for its selection for retention to represent Out of This World. ↩

Quoted in White, Armchair Theatre, p. 78. ↩

Peter Black, ‘Teleview’, Daily Mail, 17 September 1962, p. 3. ↩

Quoted in White, Armchair Theatre, p. 78. The average cost of each episode was £5,024. A breakdown of expenditure across the series can be found in White’s Out of This World scrapbook. ↩

Anonymous, ‘Not Taking It Easy This Summer’. ↩

Quoted in White, Armchair Theatre, p. 79. ↩

Quoted in Shubik, p. 37. ↩

The most famous part of Wilson’s speech, given at the 1963 Labour party conference, is commonly quoted as referring to “the white heat of technology” or “the white heat of technological revolution”, but the exact phraseology was a little different, though the meaning much the same, hence the careful use of quote marks above. Shubik quote from Shubik, p. 37. ↩

White, p. 72. ↩

I remember as a nine year old watching Pictures Don’t Lie but never knowing what it was called or what series it was from so this is a useful article.

At the end, one of the Earth radio operators runs out to look for the craft and crushes the spaceship with his shoe. I also remember the Little Lost Robot episode. At the end, the robot finally does something different to the others. Thanks.

Pingback: Level Seven (1966) | British Television Drama

Pingback: Out of This World: “Medicine Show” (August 1962) « Jacqueline Hill

Pingback: Any idea of the name of this British SciFi drama? - Science Fiction Fantasy Chronicles: forums