by DAVID ROLINSON

Today marks the fiftieth anniversary of Ray Galton and Alan Simpson’s Steptoe and Son (1962-74): on 5 January 1962, the BBC broadcast ‘The Offer’, the Comedy Playhouse one-off that led to the series that started later the same year.1 It’s a landmark series, and it’s a shame that, like Z Cars earlier this week (2 January), its fiftieth anniversary hasn’t seen an official BBC commemoration, especially since repeats continue to do decent business for BBC Two.2 It’s not that the BBC entirely resist anniversary celebrations – it’s just that those usually commemorate, and play a part in branding, currently ongoing programmes – and they have shown awareness that Galton and Simpson are among the greats of British television writing, including a profile by Arena.3 However, the anniversary does provide a welcome prod to revisit the series. In that spirit, this site presents an essay celebrating some of the series’ ideas and themes, trying to do some justice to the quality and depth of the writing.

Introduction

This essay revisits a talk I gave at a conference in 2002 – perhaps appropriately totting some old junk out of my filing cabinet. (It’s ‘new’ in the sense that I’ve never repeated it or tried to publish it elsewhere.) The conference was devoted to masculinity in literature and media between 1954 and 1963, so this piece uses that period, and the conference’s set aims, as its focus. Inevitably what follows does neglect some of the things I feel made the series great – needs more jokes – but I’ve also stripped away the more academic jargon to hopefully make it more engaging for a wider audience. But I won’t apologise for being a bit serious in order to state the case for Steptoe and Son as one of British television’s finest series.4

I aimed to use Steptoe and Son to look at how key discourses of masculinity and class moved beyond neo-realist fiction and British New Wave cinema in the early 1960s. With key authors becoming marginalised and British cinema becoming dependent upon American finance and experiencing critics’ lazy stereotyping of “kitchen sink” (as a pejorative term) cinema,5 it fell to television to represent neglected areas of British life. As discussed elsewhere on this site, television’s engagement is often credited to play strands like The Wednesday Play and Play for Today, and the new approaches of writers like Jim Allen and directors like Ken Loach (Loach in particular has often stated his reservations with the aesthetics of the British New Wave). However, social realist discourses and issues of class were also addressed in situation comedy, a form much less often discussed in academic writing.6 The most often-cited examples are The Likely Lads by Dick Clement and Ian La Frenais, Till Death Us Do Part by Johnny Speight, and Steptoe and Son.7 Creating a space for working-class representation, Steptoe and Son had a long-lasting impact on the landscape of British television fiction in various forms.

Steptoe and Son, of course, features a father and son who work as rag-and-bone men (collectors and traders in second-hand goods) living in a junk yard in Shepherd’s Bush. The father, Albert Steptoe (Wilfrid Brambell), often seems a lazy, xenophobic old man of questionable personal hygiene, who runs the home while his son Harold (Harry H. Corbett) goes out on the horse and cart to look for junk. (I say “seems” because the writing is too nuanced to let such stereotypes stand.) Harold had been taken out of school at an early age to follow in his father’s footsteps, but still dreams of finding room at the top. But, as the intensely claustrophobic first episode ‘The Offer’ proves, this is easier said than done. Harold, belittled by his father as a rotten rag-and-bone man, is desperate to move away, and reveals that he has had another “offer”, but he is trapped, by the psychological stranglehold of his father – for whom he feels obliged to care in his old age8 – and by the constraints of his upbringing. This essay will try to show how the series connects family psychology and class boundaries, and how they form the battleground for Harold’s sense of his own masculinity.

Know thy place: the junkyard

In a 1974 episode we’re told that Harold’s school’s motto was “Know thy place and be grateful”, but he can hardly avoid knowing his place.9 The junkyard setting offers an ideological and psychologised space – whether in the yard or the house, the characters are swamped with junk and debris. The mise-en-scène is cramped – often comically so – and the details in production design reveal a lot about them. They are living off the dregs of society – literally so, since their “wine cellar” is stocked from leftover bottles.10 They often get their clothes off the round, though as a mobile young man Harold takes pride in new suits – a detail resonant to viewers of Free Cinema and the British New Wave.11 Neglected by the education system, Harold is an autodidact, learning from second-hand books gained on the round. He often resembles the star of Galton and Simpson’s previous success, Hancock’s Half Hour, in which Tony Hancock’s pretensions to greatness and orations on issues whose nuances he did not entirely comprehend made him a comic inversion of the “angry young man”, the East Cheam Jimmy Porter. Steptoe and Son continues to act as a comic inversion of the British New Wave.

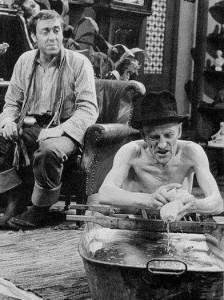

The squalor of the Steptoe house seems a far cry from the mythologised Swinging London taking place in British cinema of the time, even if the Edwardiana hoarded by the Steptoes foreshadows the fashions of Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band and Adam Adamant Lives!12 In some episodes, Harold is affluent and mobile, akin to characters in the New Wave and other forms, though as we’ll see, those tropes are inverted or satirised. One of the series’ recurring storylines is Harold’s attempt at home improvements, to match the changing material conditions of the working class. Attempts at betterment include installing a bathroom to prevent Albert dunking his pickled onions while abluting in a tin bath in the living room,13 attempting DIY central heating,14 and dividing the house into separate living accommodation in ‘Divided We Stand’, an episode that never fails to move siblings who share bedrooms.15 Every time, the result is carnage, structural damage and near-patricide. Some critics have seen this setting as anachronistic, without reading it for meaning. Are Albert’s traditional working-class values meant to seem anachronistic, an anachronistic way of life, a redundant version of dirty old masculinity? Is the Steptoes’ alienation a result of their separation from the modes of production, as they – like Britain – have moved from the industrial base to the service economy? Let’s not allow an eye for mise-en-scène to steer us into too crass a mapping of social developments onto details, but the series does at times invite a reading of the house in relation to Britain’s perceived decline. The living room is cluttered with ethnic relics of empire and Britishness – objects, costumes, photographs – constantly overlooked by a giant stuffed bear.16 This is a business powered not by the white heat of technology but by a shagged-out old horse: as Harold puts it, “a relic of our inefficient past”.17

Totting is an unusual occupation for fictional treatment, derived from Alan Simpson’s memories of his own background.18 It is important that the Steptoes live and work in the same space: though New Wave films broke new ground in showing characters at their workplaces, the focus of their narratives was often on leisure time. This seemed to reinforce Eli Zaretsky’s argument that capitalist development “created a ‘separate’ sphere of personal life, seemingly divorced from the mode of production”.19 As John Hill argued, this refusal to represent labour inhibited treatment of character, as “work is not outside and separate from the personal life at all, but a crucial determinant of how that personal life is expressed”.20 For the Steptoes, as Harold puts it, “If it wasn’t for the wall in-between, I wouldn’t know where the yard finishes and the house starts.”21 In ‘The Offer’, Harold’s attempt to escape job and family is connected, as he argued that “I’ll never make a name for myself here” as long as he is merely “and Son”. This interconnectedness of work and family is surprisingly complex – while Harold is trying to evade the know-your-place familial rhetoric of capitalist organisation, Albert represents the internalization of economic systems into the family unit, raising Harold only for manual labour.22 Albert is at times the epitome of working-class conservatism/Conservatism or, as far as Harold is concerned, a complacent dupe or a “dyed-in-the-wool, fascist, reactionary”,23 for attitudes such as these:

You’ve been reading too many books [… people] all reading books, giving themselves ideas, filling their heads up, making themselves dissatisfied with what they’ve got […] If I had my way, I’d close all the libraries, burn all the books and leave book reading to those that understands it […] book-reading leads to Communism” – Albert24

Albert rebukes Harold’s socialism, his wish to go it alone and dispense with management, with the lovely phrase, “Don’t call me ‘brother’, I’m your father”. Albert’s hold on Harold also evokes the stranglehold of class history on the construction of masculine roles. History is a constant presence. There are memories of two World Wars in which the workers were (according to the series) cannon fodder: Albert constantly describes his war experience as more brutal than Harold’s later war experience, which he describes as a “picnic”,25 and the treatment of old soldiers will come up in ‘Homes Fit For Heroes’.26 War, national identity and the Steptoes’ identities are intermingled even in their middle names: Albert Edward Ladysmith Steptoe and Harold Albert Kitchener Steptoe.27 There is also the fight against “grasping capitalists” in ‘The Siege of Steptoe Street’, with its references to the siege of Sidney Street.28 Harold often traces his failure to the 1926 General Strike as a snuffing-out of working-class potential, and asks Albert why the working class did not take their opportunity, though Albert stresses that he is “management” rather than working class and Harold accuses him of being “a traitor to the working class”.29

Stronger than Pinter: reception of ‘The Offer’ and the move to a series

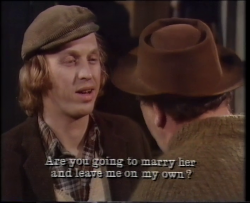

In ‘The Offer’, Harold’s desire to take another businessman’s “offer” has a clear social resonance in terms of the wider “offer” of purported new opportunities for the working class. However, in practice, Harold needs money, and he needs to use the horse to move his belongings out of the yard. Albert won’t let him use it, so he tries to pull the cart out himself, which he is unable to do. It’s a painful scene, as Harold strains at the cart, holding back tears, saying that “I’ve got to get away”. Harold is trapped, and has discovered that, beneath the rhetoric of social mobility which he quotes, nothing has changed because he is literally powerless. When first shown as a Comedy Playhouse one-off, ‘The Offer’ was reviewed with unusually highbrow points of reference for newspaper reviews of sitcoms: Ibsen, Dickens, Beckett, Chekhov (the reviewer for the Times noted its “almost Chekhovian ambience”30 ) and Strindberg. Raymond Williams located it in the literary tradition of “men trapped in rooms, working out a general experience of being cheated and frustrated on the most immediately available target: the others inside the cage”.31

Galton and Simpson have often been quoted as saying that they resisted turning this Comedy Playhouse episode into a series: “we think we’ve written a little piece of Pinter here and we can’t repeat it!”32 However, the resulting series Steptoe and Son was such a phenomenon in Britain that stories are often told about it winning Labour the 1964 General Election, as Harold Wilson urged the BBC to re-schedule an election night episode to get Labour voters out of the house.33 It is clearly a remarkable body of work. Comedy writer Denis Norden argued that television comedy’s greatest influence was “on the language, when you’ve got people like Galton and Simpson, whose writing is on a par with Pinter’s, and should be set for O-Levels in the way that it captures the idiom of people’s speech and the poetry of people’s speech.”34

However, not everyone welcomed the move to a continuing series. For Raymond Williams, the series was inevitably inferior to ‘The Offer’. Williams wrote that the form of the continuing situation comedy “prevents any full working-through”, resulting in “endless evasion and opportunism: hints and temporary effects”. However, he accepted that this pattern does capture “the continuing experience of a trapped and frustrating society”.35 Dissatisfied with the series, Williams located it alongside a period from the late 1940s to the early 1960s:

a period dominated and symbolised by Orwell’s conviction that it is all a swindle, good and bad alike: a despair that was wrought into viable commercial forms, superficially tough-minded and demotic. When I now read late Orwell or Braine or Amis or Pinter or Osborne, I have the sense of a past, and the Steptoes, essentially, belong to it.36

The format also concerned Dennis Potter, given his comments on the series in 1967, when comparing the series with Till Death Us Do Part: “Galton and Simpson’s rag-and-bone men are splendid creations, almost too brilliant for the confines of the half-hour comedy format and the cruel temptations of a studio audience.” Unlike Till Death, whose characters, he felt, “seem to expire with the final credits and re-emerge only to fight the same old battles”, for Potter “The Steptoes remain human beings: there is a flow of sympathy between them, a pathos which hardly ever topples into easy sentimentality.” Potter wondered “what heights the series might have attained” without an audience and the labelling of “comedy”. (Potter doubted “that Till Death Us Do Part will last in anything like the triumphant way as the Steptoes, good though it undoubtedly is.”)37

Williams had a point that Steptoe and Son wrought its ideas into a viable commercial form, but the argument that its tough-mindedness is superficial is more problematic. Dennis Potter – perhaps unsurprisingly for one so inspired by Williams – spoke in similar terms in that he saw Galton and Simpson “continually threaten” sitcom’s “rigid conventions”, but thought that they should “have been encouraged to fracture them altogether: half-hour, budget and all”.38 Episode after episode details Harold’s failure to escape, and I believe that this repetition of denial forms the core of the series’ power and meaning. Working-class stories often include the narrative device of the individual’s escape – from the problematised social climbing of Room at the Top (1959) to the heart-warming triumph of Billy Elliot (2000).39

“Happens all the time with married couples”: frustrated aspirations

Harold will never escape – the series form means that we are repetitively shown him smashing his head against the glass ceiling. When he tries out as a Labour candidate, he is rejected in favour of a faceless outsider intended to attract “a growing middle-class electorate.”40 His attempts to escape through creative means – literature or classical music, amateur dramatics or ballroom dancing – end in disaster. If Billy Elliot’s surname had been Steptoe, he would’ve broken his legs slipping on horse shit. Although Harold can take scraps from the rich, he is not allowed into their culture. His occasional affluence means that he can take options that were previously beyond the working class, but his belief that “if you’ve got the loot, you’re in” is constantly disproved, as disaster results from his attempts to go on skiing trips,41 join tennis clubs,42 or move to a more affluent area.43 So in Steptoe and Son, class is determined not culturally but economically. Harold needs to learn that lesson. He believes that “When I’ve got my decent clobber on I’m completely classless. Providing I don’t open my mouth I could pass for anybody.”44 While Harold resists confronting the bitter irony of that statement, Albert is, as Hancock and Nathan put it, an “implacable realist with no illusions about the nature of society and the impregnability of its defences.”45

Albert’s sabotaging of Harold’s ambitions, and their love-hate relationship, are motivated by a collision between competing definitions of masculinity. If Britain is the ‘dirty old man’ of Europe, it finds its symbol in Albert, whose pre-Suez imperial conservatism is rooted in wartime discipline and class deference. It’s hard enough for him that his son has taken his role as breadwinner – Harold berates Albert for laziness at home while he is out working, but is pulled up short by a doctor’s analysis of Albert’s loss of masculinity and self-esteem having been replaced as the head of the family (and in effect imprisoned in the domestic space). This being Steptoe and Son, the diagnosis is slightly undercut – the doctor confesses to being an ear, nose and throat specialist rather than psychiatrist – but is consistent with Albert’s own tensions.46 So, this is bad enough for Albert but he is further distanced from his son’s effete book-reading tendencies; he takes a hammer to Harold’s Wagner collection, and gets them both thrown out of an art film: given the choice between Fellini and Nudes of 1964, Albert would rather skip 8 ½ for some “bird’s” 48½.47 A shame, really, because he might have appreciated a film concerned with identity and being trapped. (Yes, I mean 8 ½.) This shows a tension that runs throughout the series: the association of culture with failed masculinity, and occasionally (but problematically) homosexuality. When Harold learns ballroom dancing, it’s the woman’s steps,48 and when he meets a man with whom he can discuss art and literature and drink fine wine, that man inevitably tries to seduce him, leaving Harold desperate to prove himself purely a “crumpet man”, at which point Albert can tearfully bid him “welcome back, son”.49 Given that Galton and Simpson worked with Kenneth Williams, it’s tempting to speculate on correlations between Albert and Harold’s relationship and Williams’s relationship with his father Charlie.

The most common source of denial in the series is Harold and Albert sabotaging each other’s relationships with women. This partly represents a conflation of class and gender politics to match the British New Wave films and the literature that preceded it, which have been accused of misogyny owing to their depiction of women trapping men in the bourgeois values of the newly consumerist society and taking them away from ‘genuine’ working-class culture.50 Harold constantly escapes the fate of the protagonists of Saturday Night and Sunday Morning or A Kind of Loving (1962). After one cruel separation, Albert gloats: “That’s the way to treat ‘em, son. I’m proud of you.”51 The episode ‘Is That Your Horse Outside?’ openly references Room at the Top and, to an extent, This Sporting Life (1963).52 Harold spends a day in bed with a higher-class woman, and naïvely falls in love, in part happy to have found someone with whom he can discuss culture and politics. But when he returns the next day, he finds the coal man in his place. Albert has to explain that she was only “after a bit of rough”. Given that, around this time, the film Tom Jones pointed British cinema in a new direction, this episode seems oddly prophetic of the way in which certain directors’ passion for working-class subjects passed, and the way that more radical filmmakers in television in the 1960s and 1970s questioned their sincerity.

Most failed relationships in the series are motivated by the major complicating factor in the series’ view of masculinity – the influence of Albert’s dead wife, Harold’s dead mother. We hear her voice, joltingly, in the ghostly shenanigans of ‘Séance in a Wet Rag and Bone Yard’, after which Harold runs off to sleep with his dad.53 However, it is usually her absence that dominates the stories. The psychological tension is often Oedipal, playfully so at times. Harold often fantasises about killing his father, and tells his mother’s photograph: “Why couldn’t it have just been you and me? Why did you need him to come along and spoil it?”54 If that wasn’t Oedipal enough, Harold at one point finds an old What the Butler Saw machine featuring his dad in youthful porn employment, and experiences trauma at this primal scene, though ultimately it is Albert’s trauma, mapped onto a class reading of the poverty that forced him into that work.55 Harold will not let Albert take another woman in his mother’s bed – “You and another woman… in my mum’s bed… As soon as she’s gone, you’re bringing strange birds back here!” – and accuses him of being a lecher (Albert’s wounded reply: “Two birds in 45 years? That ain’t leching!”)56 Pretending to be psychopathic, Harold rants a little too convincingly: “I’m not mad, I just want my mother. I want my mother.”57 That speech comes in the same episode as Harold’s solution to discovering that his dad’s new girlfriend is one of his own old flames: that she can stay but switch to his bed.58 Albert and Harold are locked in a bizarre form of marriage: after Harold is spurned on his wedding day, he takes his dad on honeymoon.59 Harold expects Albert to have his tea ready when he gets in from work, and fussily straightens his tie when they go out. In ‘Loathe Story’, an acerbic part-deconstruction of the show’s own format, Harold finally goes to a psychiatrist after trying to hack his father to death while sleepwalking, and the cause is said to be “the hypertension when two people live in close proximity in claustrophobic conditions unable to pursue their outside interests. Happens all the time with married couples”.60 This represents a state that Harold describes as “not natural”,61 but he has become too emotionally stunted, too unsure of his masculinity and class position (as always, intertwined), to strike out on his own.

Ultimately, Steptoe and Son invigorated the major themes of all great situation comedy ever since: claustrophobia, confinement and a yearning for escape. It’s striking that its central idea of disrupted domesticity – men living without women – has become a sitcom archetype. It says a lot about the reputation of masculinity in modern society that its inadequacy and failure are taken to be reassuring and comedic, yet also full of pathos. The series is often as satisfying dramatically as comically, and pathos plays an important part: as Christopher Dunkley noted, “The laughs in Steptoe are induced as often by pathos or the wry recognition of some eternal truth about the human condition as by ‘funny’ lines.”62 This even includes the statement of problematic patriarchal discourse. Harold often shares the fate of his mother, who had had a career as a teacher before Albert “soon knocked that on the head”.63 It’s hard to imagine a focus-grouped commissioning process running with a sitcom about a son who offers his father his shaving blade and encourages him to “cut your throat […] how about a wrist”,64 let alone for that series to become a massive ratings winner. There are some appalling statements from Albert which Harold is appalled by on our behalf, such as Albert’s reminiscence, complete with a wistful look in his eye: “They didn’t stand a chance, women in them days. One word out of place and she’d get a gas bracket wrapped round her head. Many’s the night she spent locked in the coal hole screaming her head off.”65 The unseen relationship between Albert and his wife conflates class and gender politics, and that relationship and the wife’s own behaviour shifts according to Albert’s willingness to wind up his son. Such comments are also part of Galton and Simpson’s taste for inverted nostalgia, as in Harold’s memories of army life: “I had foot-rot, malaria, I was wounded twice. I had three doses of dysentery. Oh God. They were the happiest days of my life.”66 Indeed, in ‘The Desperate Hours’, they envy the conditions of struggling prisoners,67 as they face their own, less literal, sentence. This is predicted as early as ‘The Bird’, 1962, when Harold states: “I’ve been a prisoner all my life” and compares his treatment with a dog that Albert had, wouldn’t let out, and left unprepared for the outside world when it escaped.

Indeed, the series’ sense of history is often sardonic. For example, there is this key speech from Harold:

Ain’t it pathetic, your faith in the healing powers of a cup of tea! […] the Englishman’s panacea! Mother just died? Oh what a shame, have a cup of tea. Just been run over? Never mind, have a cup of tea. I have been offered tea for disasters, funerals, operations, floods, wars, Dunkirk, the Blitz, Coronations, piles, hysteria, hunger marches and insomnia. Nice cup of tea in one hand and thumbs up to the camera in the other… Britain can take it! Well they can have it.

Corbett acknowledges the camera as he presents the “thumbs up to the camera” of wartime propaganda films, and the often-satirised taste for tea in British cinema – the timing of a recommended brew in The Blue Lamp (1949) being a particular favourite. (In retrospect, this speech makes it all the more poignant when you revisit ‘The Offer’ – when Harold, at his most broken, is soothed by Albert’s offer to “make a cup of tea”.68 But it’s such a lovely speech by Galton and Simpson, with “Coronations” following a string of catastrophes and being followed with cruel abruptness by “piles”, before going on to “hysteria” and “hunger marches” like a linked class narrative.

Steptoe and Son is an important class representation because, in the terms stated by Loach and others regarding radical drama, it gave its characters the dignity of being worthy subjects for drama away from stereotype. Or, as Harold put it: “I am sick and tired of being a cheerful chirpy Cockney sparrow. I am entitled to be as miserable and depressed as anybody else.”

Afterlife

The series has lived on beyond its geographical and temporal origins. The earlier reference to Strindberg is unsurprising, given Steptoe and Son’s play of neurosis, class and sexuality. Sweden had their own version of Steptoe and Son, Albert Och Herbert. Alan Simpson has recalled that, during a trip to provide extra material in the 1980s, some Swedes could not believe that the show was not their own idea.69

Indeed, despite the seemingly specifically British nature of the programme’s language and references, and what Alan Simpson calls the “myth that comedy doesn’t travel”,70 Steptoe and Son generated other remakes too, such as Stiefbeen en Zoon in Holland and Sanford and Son in America, where black actors complicated the signposting of class dimensions from the original.71

Should we be doing more to celebrate anniversaries like Steptoe and Son’s fiftieth? Primetime repeats of Dad’s Army and daytime repeats do decent business for BBC Two, so the reluctance with repeats (outwith the UKTV channels) is a shame though this also continues a long thread in discussions of television: as far back as 1967, Dennis Potter defended television from “familiar growls from those letter-writing viewers who regard any re-run of a programme which they have already seen as an affront almost too great to be endured”. He observed the recent repeats of programmes ranging from Steptoe and Son to Harold Pinter works, stressing that repeats “can be valuable”, for programme-makers, for viewers and also for critics to “add a few second (or even second-hand) thoughts to their initial assessments”.72 Perhaps, by being left to dig out the episodes, we’re able to reclaim the joy of the series.

This reclamation is important given that some programmes have revisited the series with other intentions, from grubby documentaries (in particular When Steptoe Met Son) to docudramas in which the invention, talent and fun of the series and its performers is sublimated to the revelation of personal demons and tears-of-a-clown cliché.73 The Curse of Steptoe combined the best and worst features of the BBC Four television biopic about television. It has wonderful central performances, reminds us of the esteem with which the actors were seen before they took the parts, gives a sense of the original programme in development – and a sense that this is sufficiently important to warrant such close attention – and is part of a fascinating trend in biopics to reconstruct the spaces of 1960s and 1970s television studio production. However, it also too easily conflated the entrapment felt by the characters with the alleged feelings of the actors (increasingly to the detriment of the series) and made dramatic choices that led to complaints from relatives regarding inaccuracies, resulting in changes to BBC policy and alterations that mean that the original broadcast version might never again be seen in that form; writer Brian Fillis discussed the pros and cons of the biopic form, and how it has changed, in this report on a 2011 event. I say more about The Curse of Steptoe, and the “television biopics about television” sub-genre, in a new article forthcoming in 2016.

Clearly, I didn’t finish with Steptoe and Son in 2002. In a book chapter in 2011 I discussed Steptoe and Son, Rab C. Nesbitt (1988- ), Only Fools and Horses (1981-2003), The Royle Family (2000- ) and other sitcoms in a long history of TV social realism, which also does more with the idea treated briefly above related to the alleged radicalism or otherwise of particular television forms.74 I also discussed this a little in my post about John Sullivan elsewhere on this site.75 I’ve also used Steptoe and Son in teaching over the years: certainly whenever I tried to ground introductory audience-based film theory I always like to use the Steptoes’ ill-fated visit to Fellini’s 8 ½ in ‘Sunday for Seven Days’. There is still much more to be said about this, Hancock’s Half Hour and also some of Galton and Simpson’s less celebrated work.76

In the meantime, how about a nice cup of tea?

Thanks to John Williams for drawing my attention to the Steptoe and Son coverage in Dennis Potter’s piece ‘Repeats’. Elements of my essay first appeared as a conference paper at the University of Surrey Roehampton conference “The Importance of Being Arthur: Representations of Men and Masculinity 1954-1963, on 13 July 2002. It is posted here with substantial revisions, new material and endnotes.

Originally posted: 5 January 2012.

Updates:

25 January 2012: added new notes from Dennis Potter’s reviews.

Early 2012: added a small number of points, drawn from rewatching further episodes, such as the block quotation from ‘The Economist’ and some comments in endnotes.

2 February 2016: substantial revision – added new images from ‘The Offer’ and from overseas remakes of Steptoe and Son; moved existing images and YouTube extract to different stages of essay; added sub-headings as part of clarifying structure; made many minor corrections or alterations to phrasing; amended tenses and references relating to the fiftieth anniversary and then-current BBC Four drama strategies; deleted in-text acknowledgement of the addition of new comments; new comment about middle names; moved some sections (such as Dennis Potter’s comments on repeats and my comments on revisiting Steptoe after 2002) to different stages of the essay; referred to new 2016 piece.

4 September 2020: slight rewording to remove specific mention of the Second World War after a reader comment.

6 October 2020: added endnote to clarify (and provide evidence) that the Second World War mention was correct but that Galton and Simpson changed the chronology of Harold’s wartime experience between the 1960s and 1970s runs, so that the war in which he fought changed.

8 November 2022: deleted one footnote relating to wanting to write something new about the programme.

You might also be interested in Walter Dunlop’s review of a repeat of ‘The Desperate Hours’ and comments on the non-celebration of the 50th anniversary.

I should explain my last reply about rewording rather than simply changing the war that I mentioned. Confusingly, my article and your reply were BOTH correct. In ‘The Bird’ (1962) it is explicitly stated that Harold is 37 and that he joined the army at 18 (approximately 1943) for four years. When Albert talks about the local area during the Second World War, Harold says he was out fighting for King and Country. This is where Albert (for the first time, but it becomes a running joke) says that his experience in the First World War was not a picnic like the one that Harold was in. In an interview with Robert Ross, Alan Simpson said “Harry had, originally, in our minds been involved in the Second World War.” However, when Steptoe and Son came back in the 1970s, Galton and Simpson changed some of the chronology because Harold was, despite the gap between the 1960s and 1970s series, roughly the same age. So, said Simpson, “we changed Harold’s military background to the Malaya conflict.” (Simpson said that Harold was 37 in 1962 and 39 in 1974. Galton said that “it seriously buggered up the our histories of the Steptoes.” No wonder finding a precise (or, better, vague) wording was tricky. DR

Thanks for your comment. Yes, my wording muddled that point (“the next war” would have been better as “subsequent wars” or specifically “Harold’s war experience”) to make a clunky sentence flow. I’ve reworded it a little. This is a really interesting topic that deserves a piece of its own, given the ways in which other comedy writers around this time drew from wartime experience and National Service. DR

Very interesting article but just a slight quibble. Harold served in Korea, not WW2.

Interesting that you should note the similarities between Albert and Harold’s relationship and Kenneth’s and his father, I too had noticed this.

Pingback: this time next year, Rodney, we'll be.... -

Thanks, you’re very kind. Yes, it’s fascinating that Williams – and others including Dennis Potter (whose comments I’ve added to the piece) – were so interested in it and its potential. Reminds us of just how ground-breaking and surprisingly complex it was, at least in the 1960s.

Excellent, insightful piece, articulating the pathos and social commentary that makes Steptoe so resonant. As an academic and huge Steptoe fan myself, I’m made up to know that Raymond Williams wrote about the show, albeit somewhat critically.