by DAVID ROLINSON

Nine parts. Writer: Alan Plater; Adapted from (novel): J.B. Priestley; Music by: David Fanshawe; Producer: Leonard Lewis; Directors: Bill Hays, Leonard Lewis

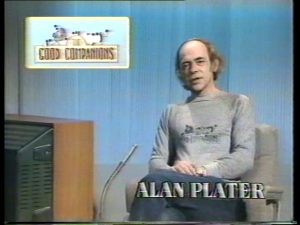

A “tuneful tonic of merriment and mirth”, The Good Companions is a nine-part Yorkshire Television serial about a touring concert party adapted from J. B. Priestley’s famous 1929 novel.1 It was adapted by Alan Plater, who described the serial as one of his happiest working experiences, but added that it was “interesting but flawed, and didn’t really catch on”.2 That’s a fair assessment, but the serial is certainly more interesting than flawed. Like the two previous film adaptations, the serial risked being written off as undemanding, suffering in part because of the reputation of the source novel. Writing about the 1933 film version, Charles Barr observed that the novel “never had much currency in academic circles”, with supportive opinions outweighed by the impact of “the vinegary attacks on the book and the novelists by the two Leavises”.3 Priestley himself argued that “[s]ome severe critics dislike” stories in the picaresque tradition of “huge wandering tales” as these are “too rambling and easy for them”.4 However, the serial’s ability to parallel the book’s feel-good, episodic qualities is also one of its main strengths. With composer David Fanshawe setting Plater’s lyrics to a variety of song styles, and a lively ensemble cast relishing on-stage music hall scenes and off-stage full production numbers, this is a witty and unashamedly fun serial. The Network DVD release also comes with the 1980 tie-in documentary On the Road, in which Plater interviews Priestley, compares the serial with previous film versions and provides behind-the-scenes footage.5

First shown on ITV between November 1980 and January 1981, The Good Companions was shot on video, in studio and on Outside Broadcast at locations including Scarborough, Llandudno, Bradford and the Cotswolds. Each episode moves the story along chronologically, but also jumps back in time to give the background of characters, who take turns dominating episodes. Throughout the serial, Leslie Sands’ voice-over gives the flavour of Priestley’s prose, interceding now and again with thoughts on life, time and storytelling (“coincidence is a potent influence on the affairs of mankind”) or telling us that we’ll return to an event or character later. (Although the serial lacks the 1933 version’s device of primary characters replying to the narrator upon their introduction, there are other integrative devices including on-screen captions as types of chapter heading.) In the first episode, Jess meets Miss Trant, and both meet the troubled Dinky Doos, whom Miss Trant will of course save. But then we flashback to how Jess got here, losing his job and running away from Bruddersford – that “amalgam of Huddersfield and Priestley’s own city of Bradford”6 – in misadventures which include guest turns by Alfred Lynch (who returns later) and John Savident. The troupe isn’t cemented until the third episode (when the Dinky Doos and newcomers become the Good Companions), and this might explain why the first episode is the most difficult to engage with. However, there is an immediate sense of where the troupe are heading – the rehearsal script notes that the titles are “in effect a quotation from a later episode […] when the Good Companions have their greatest triumph” – also, that “The song is jolly, boisterous and maybe a little silly but who cares?”7

It is therefore unsurprising that situation, tone and pace are more engaging in subsequent episodes as the troupe gets together. Characters get variations on the theme ‘On the Road’ as we are given more backstory: the search for independence by Miss Trant in the second episode (guest starring Nigel Hawthorne), and Inigo Jollifant (a winning Jeremy Nicholas) rejecting the prune-plagued tyranny of teaching at a minor public school in the third episode (guest starring Nigel Stock). He also meets “four-times-round-the-world” Morton Mitcham, played by Bryan Pringle with such endearing fruitiness that the DVD release might just count towards your 5-a-day. Judy Cornwell is fabulous throughout, communicating Miss Trant’s naive enthusiasm with lip-biting sparkle – as Peter Fiddick wrote in The Guardian, “She never steps outside the character for a second, yet fills it with fun, song, dance, timidity, steel, and a certain longing”8 – while Jan Francis is an energetic and engaging Susie Dean. There are many individuals worthy of praise – John Stratton brings pathos to Jess Oakroyd, a part that could easily descend into stereotype – but one of the serial’s joys is the way the ensemble sparks off each other. As Fiddick argued, the serial is “full to the brim with the sort of character acting (and being just slightly aware of the techniques at work is half the fun) that gives British television much of its richness.”9

It is therefore unsurprising that situation, tone and pace are more engaging in subsequent episodes as the troupe gets together. Characters get variations on the theme ‘On the Road’ as we are given more backstory: the search for independence by Miss Trant in the second episode (guest starring Nigel Hawthorne), and Inigo Jollifant (a winning Jeremy Nicholas) rejecting the prune-plagued tyranny of teaching at a minor public school in the third episode (guest starring Nigel Stock). He also meets “four-times-round-the-world” Morton Mitcham, played by Bryan Pringle with such endearing fruitiness that the DVD release might just count towards your 5-a-day. Judy Cornwell is fabulous throughout, communicating Miss Trant’s naive enthusiasm with lip-biting sparkle – as Peter Fiddick wrote in The Guardian, “She never steps outside the character for a second, yet fills it with fun, song, dance, timidity, steel, and a certain longing”8 – while Jan Francis is an energetic and engaging Susie Dean. There are many individuals worthy of praise – John Stratton brings pathos to Jess Oakroyd, a part that could easily descend into stereotype – but one of the serial’s joys is the way the ensemble sparks off each other. As Fiddick argued, the serial is “full to the brim with the sort of character acting (and being just slightly aware of the techniques at work is half the fun) that gives British television much of its richness.”9

If there is any lack of cohesion in the early moments – or more likely a desire to get on with the troupe’s story – then that is appropriate to the material. As Charles Barr argued, Jess, Susie and Inigo “have escaped from a parody of community” and will find “[m]ore genuine versions of community and companionship” with the Good Companions.10 Indeed, this “represents a typical Priestley structure” according to Barr, a structure that he finds also in Priestley’s Benighted (1927, filmed as The Old Dark House (1932)) and explained by Priestley himself on-camera in the Ealing film version of They Came to a City: “Let’s suppose we took a cross-section of our people… let’s imagine these people suddenly find themselves out of their ordinary surroundings”. In this way, characters are, in Barr’s description, transferred, “to their bewilderment, from their everyday lives into a new space where they are forced to interact, in a sort of workshop for constructing a good society”.11 It is therefore perhaps appropriate to share a sense of frustration or disconnectedness in the serial’s opening sections.

A more prosaic reason for the sense of the serial starting slowly is that episodes two and three bring welcome variations in light and shade, from the startling expressionism of Static Three’s avant-garde manifesto, to the flesh-consumed-in-fire Second Resurrectionists. But things really get going in the fourth episode, with rehearsals, the adorable designer Miss Thong and the troupe’s riot at Sandybay, while Miss Trant faces her family’s disapproval, which prompts her to lead a massive song-and-dance number on the pier. The fifth episode takes us back to see the composition of their songs, turns a mundane train journey into a jolly production number (‘Change at Hicklefield’) and sets up a key love story (of sorts). A sentimental character is described as having a “mind like a cheap Christmas card”, but in case you’re unfairly thinking that about the serial itself, the last four episodes hit top gear. Episode six is particularly strong, with light, shade and tension. Jess confronts his past, and the troupe endures a terrible run playing deteriorating shows (“I’ve had more fun watching a hen sit”) to tiny audiences (“Mr and Mrs Crabtree”), in a depression-marked small town, as tensions undermine their friendliness and loyalty. Episode seven sees the “tatty” troupe under threat from Bill Dean’s jealous cinema owner, marriage, ambition and veiled warnings. Episode eight has guest roles for Roy Kinnear and Barry Jackson, and features an apocalyptic performance and a memorable punch-up (“caught up in the bewildering mechanisms of life”). Episode nine (guest starring Harold Innocent) wraps up individual stories, culminating in a long epilogue in which every regular sings a variation on ‘My Dream of Life’, and the deliberately artificial renderings of these and a woozy effects-laden curtain call (indeed a dream of life) take us closer to Pennies from Heaven than Glee. Priestley himself gets to read the final lines. It did take me a while to get into the serial on first watch, and perfection is not to be found – situation and tone don’t immediately gel and the class types are inevitably broad – but I was sad to get to the end: as always, Alan Plater writes characters with such warmth and nuance that you enjoy spending time with them.

A more prosaic reason for the sense of the serial starting slowly is that episodes two and three bring welcome variations in light and shade, from the startling expressionism of Static Three’s avant-garde manifesto, to the flesh-consumed-in-fire Second Resurrectionists. But things really get going in the fourth episode, with rehearsals, the adorable designer Miss Thong and the troupe’s riot at Sandybay, while Miss Trant faces her family’s disapproval, which prompts her to lead a massive song-and-dance number on the pier. The fifth episode takes us back to see the composition of their songs, turns a mundane train journey into a jolly production number (‘Change at Hicklefield’) and sets up a key love story (of sorts). A sentimental character is described as having a “mind like a cheap Christmas card”, but in case you’re unfairly thinking that about the serial itself, the last four episodes hit top gear. Episode six is particularly strong, with light, shade and tension. Jess confronts his past, and the troupe endures a terrible run playing deteriorating shows (“I’ve had more fun watching a hen sit”) to tiny audiences (“Mr and Mrs Crabtree”), in a depression-marked small town, as tensions undermine their friendliness and loyalty. Episode seven sees the “tatty” troupe under threat from Bill Dean’s jealous cinema owner, marriage, ambition and veiled warnings. Episode eight has guest roles for Roy Kinnear and Barry Jackson, and features an apocalyptic performance and a memorable punch-up (“caught up in the bewildering mechanisms of life”). Episode nine (guest starring Harold Innocent) wraps up individual stories, culminating in a long epilogue in which every regular sings a variation on ‘My Dream of Life’, and the deliberately artificial renderings of these and a woozy effects-laden curtain call (indeed a dream of life) take us closer to Pennies from Heaven than Glee. Priestley himself gets to read the final lines. It did take me a while to get into the serial on first watch, and perfection is not to be found – situation and tone don’t immediately gel and the class types are inevitably broad – but I was sad to get to the end: as always, Alan Plater writes characters with such warmth and nuance that you enjoy spending time with them.

The joy of the serial and of Priestley’s original (as in Charles Dickens’s The Pickwick Papers, which inevitably springs to mind at times), is in the characters we meet, and in seemingly incidental details and prose. As Barr indicated earlier, critics expected more weight from the novel – Richard Church once wrote that Priestley lacked the social and economic analysis of Thomas Holcroft’s Alwyn, which had the same basic idea in 1870 – and Plater’s apparent lightness often conceals more steel.12 But lightness and warmth are often underestimated by critics: reviewing Priestley’s Instead of the Trees in 1977, Anthony Burgess wrote that Priestley’s “critics have not taken him seriously enough. Let them make this book a pretext for a revaluation which avoids […] condescension”. Disagreeing with Priestley’s own opinion that he had written far too much, Burgess stated that he had “hardly written a word too many” and that his “oeuvre coheres into a unity marked by a strong and inimitable personality.”13 If The Good Companions feels escapist, then that is hardly surprising: Priestley had endured a decade of personal tragedy, and as he says in On the Road, he had a “feeling of something coming loose” when writing the book.14 Published in 1929 in a wall-bracket-troubling 250,000 words, the book was a huge seller, propelling Priestley to the high profile he’d keep for life. The reviewer who thought it would be “forgotten in six months” is currently 83 years out and counting.15 As Keith Waterhouse wrote in 1973, critics have “always been wary of Priestley”, who for Waterhouse was “the last of a great line of authors who knew how to teach their readers”, like Wells, Chesterton and Bennett. Writers now “don’t even try to reach the ordinary man. They write about problems of identity for people who can afford to worry about such matters”.16 Waterhouse’s thoughts are in keeping with Priestley’s opinion that critics, “the Eng. Lit. boys”, based their standards on “the highbrow-lowbrow structure that intellectuals erected as a defence when they saw the mass media beginning to spread”.17

Those last few quotations come from Alan Plater’s own research files on Priestley, which are available in the Alan Plater archive in the Hull History Centre. Like the adaptation, those quotations are interesting for the further reason that Plater too had a prodigious, varied and accessible body of work. I’m not going to apply Priestley’s point to television because so many television writers are neglected, whether writing in “difficult” forms or the Plater/Jack Rosenthal model of complexity treated with accessibility, warmth and humour. (The comparison would also be complicated by the fact that Priestley wrote for television. See, for instance, his Armchair Theatre piece ‘Now Let Him Go’ on Network DVD’s Armchair Theatre Volume Three.) To borrow Waterhouse’s words about Priestley, Plater “can make you look at old things in a new way, and what is perhaps more important, he can force you to look at new things in the old way.”18 The DVD’s release in 2011 was well-timed: Priestley’s reputation has rightly moved on and The Good Companions had recently returned to the stage and to radio, in an adaptation by Eric Pringle, the previous year.

Plater worried whether “we all became intoxicated by our own cleverness”, particularly his own lyrics, as he thought he’d “fallen in love with convoluted triple-rhyming schemes” resulting in “Too many words”.19 He had a point about the wordy lyrics: in the published sheet music, David Fanshawe said that Plater’s “deceptively simple lyrics have been a joy to set – or should I say a puzzle to get!”20. However, they usually feel organic. Fanshawe relished the “opportunity to write featured songs, dances, choruses, duets, quartets, solos for banjo, piano to full orchestrations”. Some of the actors “had never sung in public before”, and their “voices became the discipline of the music”.21 This feels appropriate for the characters too. Similarly, the rehearsal script notes that the opening song contains “a simple dance routine, geared to the ability of the least able dancers”, a reference presumably to the characters but possibly also applicable to the cast.22 Plater noted that the nearest they got to jazz was in the first episode, on ‘The Original Bruddersford Dixieland Ragtime Band’ (a song that Adler “really hated”), featuring trumpet by Kenny Baker.23 True, the accompanying soundtrack album “didn’t exactly sell in millions”, to the “chagrin” of YTV; as Plater put it, “Parodies of early Benjamin Britten were never likely to make the charts”.24

Plater worried whether “we all became intoxicated by our own cleverness”, particularly his own lyrics, as he thought he’d “fallen in love with convoluted triple-rhyming schemes” resulting in “Too many words”.19 He had a point about the wordy lyrics: in the published sheet music, David Fanshawe said that Plater’s “deceptively simple lyrics have been a joy to set – or should I say a puzzle to get!”20. However, they usually feel organic. Fanshawe relished the “opportunity to write featured songs, dances, choruses, duets, quartets, solos for banjo, piano to full orchestrations”. Some of the actors “had never sung in public before”, and their “voices became the discipline of the music”.21 This feels appropriate for the characters too. Similarly, the rehearsal script notes that the opening song contains “a simple dance routine, geared to the ability of the least able dancers”, a reference presumably to the characters but possibly also applicable to the cast.22 Plater noted that the nearest they got to jazz was in the first episode, on ‘The Original Bruddersford Dixieland Ragtime Band’ (a song that Adler “really hated”), featuring trumpet by Kenny Baker.23 True, the accompanying soundtrack album “didn’t exactly sell in millions”, to the “chagrin” of YTV; as Plater put it, “Parodies of early Benjamin Britten were never likely to make the charts”.24

Comparisons with earlier adaptations of Priestley’s novel are useful to an extent. Helpfully, the documentary On the Road uses extracts to compare the handling of key scenes from this version with their handling in two previous film adaptations – for instance, visiting the 1933 film, Plater seemed pleased to identify (according to the production files) “Key scenes that seem to run in parallel” with his serial.25 Victor Saville’s 1933 version, described by Brian McFarlane as “a fine, unmannered adaptation”,26 starred John Gielgud and Jessie Matthews: the latter became a big star and said at the time that she had “enjoyed making this more than any other film”.27 Charles Barr felt the 1933 version “overdue for rescuing for obscurity”, and his choice if “one had to nominate a single film to represent 1930s British cinema”.28 As with many adaptations, there is as much interest in what each version reveals about its own time as there is in its fidelity to the source. Barr persuasively relates the 1933 film’s sense of teamwork and its integration of people from different walks of life across the country into a form of community (discussed above) to the film’s own teamwork, since personnel involved with the film would go on to be key players in the subsequent Second World War propaganda effort: Priestley of course, but also the Crown Film Unit (via Ian Dalrymple here) and Ealing (via Michael Balcon here) – the latter two groups making wartime propaganda featuring “celebrations of teamwork in action, of people coming together from diverse backgrounds to serve a common cause”.29

As Steve Chibnall noted, the 1930s version happened when musicals were “a familiar and popular part of British film culture”, but by the time of the 1957 version (directed by J. Lee Thompson and featuring Celia Johnson and Eric Portman amongst its cast), musicals were a “rarity”.30 Thompson had not been keen on making the film until his studio head reminded him that Thompson’s superb Yield to the Night (1956) had lost them money. For Chibnall, it was a “mistake” to try “to spruce up J.B. Priestley’s tired old nag and turn it into a joy ride for teenagers” in the period of Rebel Without A Cause (1955), The Blackboard Jungle (1955) and Rock Around the Clock (1956).31 Although the film “tells the story of two young people’s attempts to break out of a mundane and oppressive environment”, this version’s title song – “Good Companions, That’s What People Out to Be” – “effaces all suggestion of a generation gap”. Therefore, as Chibnall puts it, its “values, like its style, remain more rocking-chair than rock and roll.”32 Like Chibnall, John Mundy notes the high production values, effective choreography, Technicolour and Cinemascope, but finds that “the film mixes its messages” because of “trying to update the original concept and centring it on Susie Dean’s (Janette Scott) attempts to escape from the outmoded variety circuit towards more contemporary stardom and affluence”.33 The Evening Standard‘s reviewer argued in 1957 that Thompson “put his players in a no-man’s-land” by “bringing the action up to date”.34 Chibnall stressed that Thompson was “a great admirer of Priestley’s work”, and so wanted “to retain some of the romanticising of theatrical life, even the lives of mediocre performers in unglamorous venues”, but this had to be somehow balanced with “Susie’s desire to break away”, and the attempt to bring the events into the then-present day whilst failing to engender “drama and pathos” when confronted by, in Chibnall’s view, “a narrative which is hackneyed and characterisations which are half-hearted”.35

Clearly Plater’s version, which avoids attempting to bring the action up to date, should be vulnerable to these sorts of concerns at the end of the 1970s and start of the 1980s: for rock ‘n’ roll read post-punk, for the sense of looking back criticised by Chibnall see the political climate of the 1980s which fed, or fed from, cultural representations of nostalgia and heritage. However, just as this connection can sometimes be essentialised – critics are keen to stress the sometimes neglected critical qualities of Chariots of Fire (1981) – so the timing of The Good Companions is less anachronistic than it may appear. (This is even without attempting a political reading of the story’s interest in amateurs/communities coming up against profiteers, a time-specific reading which would need a lot of work to avoid glibness, given the ‘noise’ at work in the presence of layers of the book and previous versions.) Hollywood musicals in the period also show a play of nostalgia in films such as New York, New York (1977) and Grease (1978), although here the past becomes a genre and nostalgia an imagined or constructed state, as musicals were a problematic frontline in Hollywood’s engagement with cinema’s changing demographics (but then, 1970s Hollywood was full of reference to, and unpicking of, classical genres in a way that might itself seem to be as backward-looking as the features that Chibnall and other critics found in the 1950s Good Companions). Of more relevance to us (my polite way of saying that I don’t know much about the study of film musicals) is the fact that The Good Companions comes at the end of a cycle of television musicals, from Howard Schuman’s Rock Follies36 to Dennis Potter’s Pennies from Heaven.37 Those pieces are clearly less conventional and comparisons are fraught with enough complications to put me off, but there are connections: Bill Hays, one of the directors of The Good Companions, was one of the directors of the Schuman serial.38 Like producer and fellow director Leonard Lewis, Hays had worked with Plater on previous dramas, including the superb Softly Softly episode ‘Going Quietly’ and the one-off Party of the First Part, which shared actors with The Good Companions including Jan Francis. (Indeed, familiar faces abound: Bryan Pringle, for instance, was a veteran of Close the Coalhouse Door.) In his obituary for Hays in 2006 , Plater described this former miner’s son as a “renaissance man” and “one of the brightest, most versatile and certainly most cavalier” of that generation, and the OB-unit-doing-MGM ambition of this serial is some achievement.

The On the Road documentary is therefore more than entitled to draw comparisons between (or, in its more fitting language, take “an affectionate look back at”) different screen versions of The Good Companions, and its engagement with the strengths and dangers of adapting Priestley’s novel adds to the sense of this as a thoughtful accompaniment to the serial. In fact, the production files for On the Road show that the documentary’s concept and structure were Plater’s, and although he said he wanted to avoid “the full Bragg bit”, he appears on-screen interviewing Priestley.39 Priestley also visits the cast on location, which was again Plater’s idea. Unlike the serial, the documentary (directed by Mervyn Cumming) is made on film. The documentary is a welcome and impressive addition to the DVD set, though the picture quality is variable, because it’s from an off-air video recording (the only copy ITV have in their archive). The serial itself has no such problems, and the ad caps are present and correct, which matters particularly when the episode’s music runs into them.

Of course, the use of music can be seen in another context: the body of work of Alan Plater. As Peter Fiddick argued, “for all the literary paternity and nostalgia” in the serial, it was “very much a thing of its own”, which he mentioned alongside, despite its “very different voice”, Plater’s Trinity Tales.40 Plater often uses music to investigate situation and character, from jazz as metaphor in Misterioso (1991) and expression in the Beiderbecke series, to the Watersons’ folk music in Land of Green Ginger, which as Plater argued, “not only reflected the action, it helped to generate and inspire the action”. Plater contrasted this with the way that “most music in film and television tends to be called [accurately]… ‘incidental’. It underlines the moments – scary bits, sad bits, look-behind-you bits. It tells the watchers what they should be thinking and […] feeling […] on the assumption that they’re too stupid to work it out for themselves.”41 As I’ve argued of Land of Green Ginger, the use of music in the movement between particular scenes works in a politicised space, connecting region, history and community: though a very different type of production from The Good Companions, it was described by Nancy Banks-Smith as “not so much a play, more a local musical: plaiting script, songs and scenery in about equal amounts”.42 On the Road also gives another insight into the combination of lyricism and naturalism in Plater’s work – making him a “gritty Northern surrealist”, a phrase he reminded me of in interview43 – as he questions Priestley on the novel’s “stumbling chronicles of a dream of life”, reality and fairytale. Priestley’s reply: “a man may offer you the real world and not try and move out of it, and yet the same time his mind may work in such a way that the real world becomes also a fairytale world. Dickens is a very good example of that”.44

Although Plater acknowledged the serial’s failings, he fought back against its harshest critics. The first episode was savaged on the review programme Did You See…? by panellists Michael Hastings, Larry Adler and Christopher Hitchens.45 Playwright Hastings, for whom all of Priestley’s dramatisations were “eminently resistible” with their “curiously sentimental” and “nostalgic” content, thought that “the director has sat back and gone to sleep”. Furthermore, he thought that there was “a quality which is unconscious in the writing and in the dramatisation which seems to put the blame on the women”. Hitchens found it “very tough to watch”, thought that “Yorkshire sentimentality is to sentimentality what Yorkshire pudding is to pudding” and described Priestley as “one of the great bores of the century”. Adler argued in the third person that “it was the BBC’s revenge against Larry Adler […] to make me sit through it. I thought it was awful”. As a musician, he thought the songs “corny, dreadful numbers”. Although Hitchens thought that Nigel Stock was “the only actor of any merit in the thing”, Hastings and presenter Ludovic Kennedy advanced the case for Bryan Pringle, though his lack of skill with a banjo annoyed Adler. In response, Plater sent them “exceedingly angry” letters,46 though noted that he and Adler became “lifelong friends” as a result of their correspondence.47

This savage criticism was not universally shared. Later in the run, Peter Fiddick found it “not merely charming but skilfully crafted”, benefiting from “a characteristically economical Plater script, never using two words where a nod and a wink will do, and David Fanshawe’s music, which for me hits just the right note of affectionate pastiche.”48 Overall, the serial is lots of fun, and it’s obvious that it was a creative, enjoyable collaboration. Plater’s archival holdings on the serial contain many treats, including Plater’s lovely gift to colleagues, a hand-drawn Good Companions Colouring Book, inscribed as “An Alan Plater Thank You Production with Love”.49 In On the Road, Plater tells Priestley that writing the adaptation gave him “one of the most joyous years” of his career.50 Therefore, it’s surprising to see Plater in his memoirs asking: “What went wrong?” He wondered whether “we all had too good a time”, that whilst work should be fun, the audience should have fun too, and “We sing the song but don’t invite the audience to join in the chorus”.51 It’s interesting that Pennies from Heaven, for all its anti-naturalistic devices, feels more confident in playing its musical pastiches to the viewer rather than others in the scene.

There is one final reason to cherish The Good Companions: without it, we might not have got the Beiderbecke serials. Yorkshire TV’s David Cunliffe, Executive Producer of the serial, thought that The Good Companions would last thirteen episodes, but Plater thought he could adapt it in nine, and to fill the other four weeks, proposed what became Get Lost!, the first Beiderbecke in all but name. As Plater put it in Doggin’ Around, “they were innocent days”.52 YTV let the Dormouse label do the Beiderbecke soundtrack album (which became a hit), probably because “they still had a warehouse stacked high with unsold LPs of The Good Companions music”.53 I hope the DVDs don’t face the same fate, because you’d be missing a treat.

Originally posted: 30 September 2012

[This piece first appeared on the Tachyon TV website in September 2011. It is presented here with substantial revisions, including new material and endnotes.]

Updates:

1 October 2012: corrected minor typos, added missing page numbers, added two endnotes and moved one image.

15 November 2015: added a new paragraph on Did You See (which included a sentence moved from the start of the essay and from an endnote). Added an image from Did You See. Broke up comments on the serial’s critical reception (moving most of this material to the paragraph following the paragraph on Did You See).