by JOHN WHEATCROFT

Writer: Alan Plater; Adapted from Chris Mullin; Director: Mick Jackson

Political drama which carries a left-wing punch can usually expect to find a few dissenters among the majority of journalists – or at least their employers – for whom such views are anathema; it’s easy to review the politics rather than the art. It’s a huge testimony to Alan Plater’s skill as a dramatist that A Very British Coup was received with equal acclaim by commentators from every shade of the political spectrum. Plater believes that the right-wing press can sometimes be more generous than the left, so long as they understand that no attempt is being made to convert them.1

The three-part Channel 4 dramatisation2 of Chris Mullin’s 1982 novel of the same name, A Very British Coup is about the election of a genuinely socialist government, headed by former steel worker Harry Perkins (Ray McAnally). The drama is hardly a call to arms to vote Labour, because, as Plater points out, no government has ever pursued such an agenda.3 However, Perkins proves to be a different kettle of fish, as even his opponents such as Secret Service head Sir Percy Browne (Alan MacNaughton) have to admit, and he will not be deflected. Perkins continues on his socialist path with something as close to total integrity as politics allows. This makes A Very British Coup quite different from many left-leaning dramas, as Mark Lawson remarked: ‘Political drama on television tends to pursue the view that Labour leaders willingly surrender their beliefs in power. A Very British Coup is about something darker, the theft of good intentions.’4

Plater sugars the pill by employing the lightest of touches. Like Toto Le Héros, (1991), the Belgian black comedy in which an old man tries to destroy his childhood enemy, A Very British Coup is a downbeat story told in an upbeat fashion. Director Mick Jackson observed: ‘The joy of working with Alan Plater is that you can make a drama about something very serious and not appear to be.’5 Jackson’s role in creating this mood should not be underestimated. The first 20 minutes of A Very British Coup is a giddy roller-coast ride. Perkins is elected to massive popular acclaim and the establishment looks on with growing concern. Jackson cuts crisply between the euphoria of crowd scenes, such as Harry walking from Buckingham Palace to Downing Street carrying his Sheffield Wednesday bag, to the interiors where a handful of bureaucrats are already plotting.

All this comes to a sudden halt when Harry arrives at 10 Downing Street to meet his huge staff. From here the pace slows as the new Prime Minister has to take stock. The election-winning euphoria is over. As Plater put it in interview, ‘The sudden change of tempo shows us that this is where the hard work has to begin’.6 The mood of reflection continues as Perkins goes into the Cabinet room. Plater’s writing reflects Perkins’ personality brilliantly. “You can almost touch the history,” he says, as most of us might. But then he adds: “And there’s the odd whiff of betrayal, we must do something about that.”

Jackson, director of the BBC’s nuclear holocaust drama Threads (1984), has a background in documentaries, including the corporation’s long-running science series, Horizon, for which he directed The Double Helix (1987), a drama about the discovery of DNA’s structure. Plater says that Jackson was very good at conveying information visually – such as through the shots of banks of computers showing stock markets falling rapidly – and he observes that you see a lot of these techniques used routinely now in news and current affairs reporting.7

Analyse any brief section of A Very British Coup, and you will be struck by how much ground it seems to cover, and how much it tells you. When Perkins gives his speech on television in which he says he is going to call an election, a soldier’s epaulette at the front of the screen goes in and out of focus, presaging the likely military intervention to come. Nancy Banks Smith picked up on this, commenting: “There’s hardly a shot which does not show two things at once, rubbing them together like a spark.”. The drama assumes, she says, the ‘quick televisual mind’ with which Alan Plater always credits his audience.8 Plater says: ‘I take the view that the audience is as bright as I am. Armando Iannucci said that there is too much television these days made by people with degrees, creating programmes they think are suitable for people who do not have degrees. Television viewers have seen hundreds of films. They have an instinctive understanding of the grammar of movie-making. When Harry Perkins whistles the theme music [Mozart] while peeing we know that this is an educated man as well as a steel worker, and the viewers will pick that up.’9

A Very British Coup starts with a petrol bomb exploding. This image, together with Harry Perkins’ neo-biblical voiceover explaining the chaos into which the UK has descended, is tougher than the opening of Chris Mullin’s novel. It has to be, because the political landscape had changed in the six years between the book’s publication and the first screening of Plater’s work; the scene has to be set in such a way that public disaffection could make a left-wing government possible. In the late 1980s, that wasn’t the case. It really looked as if Thatcherism could be around for ever.10 However, as Mullin remarks in the preface to the 2006 edition of his novel, the proposition was ‘not as fanciful as it now seems…. [in 1980, when he conceived the idea]…there was a real possibility that the Labour Party would be led by Tony Benn’.11 Pre-Falklands, and with rapidly rising unemployment, Thatcher seemed to be vulnerable.

Plater’s ending is a long way removed from Mullin, too. In the novel, the cabinet’s token ‘moderate’, Wainwright, becomes PM and Perkins eventually returns, as a broken man, to the Commons. In the TV drama, Perkins has called an election and the viewer can infer from the overhead drone of helicopters that the military is poised to oust Perkins if, as seems likely, he wins. The final draft of Plater’s script makes no mention of a chilling addition to the screen version: a BBC newsreader’s voiceover which puts the constitutional crisis second on the news behind an earthquake in Santiago.12 It prompted one of Plater’s admirers and regular correspondents to write to him saying: ‘How did you get away with it?’13

In fact, Plater admits that there was much debate about the ending, and thinks that the newsreader addition, with its reference to Chile, might actually have been Jackson’s work. It can hardly be a coincidence that the country chosen for the earthquake had been the subject of a vicious military coup in 1973. For left wingers, Chile was a cause célebre. Plater describes the nation’s name as a ‘loaded word’, one of several in A Very British Coup. “Another example is where Perkins meets his team at no. 10 and says he is looking forward to meeting them collectively, the sort of word which the establishment Apparatchniks will hate,” he says. One of Plater’s friends was moved to write: ‘Isn’t it about time you became a full-time writer/script editor of the Labour Party?…that dry irresistible wit of yours would destroy Margaret Thatcher overnight?”14

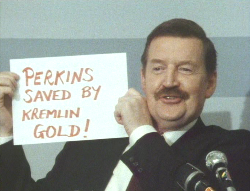

A rare dissenting voice among the critics came from The Times in whose correspondence columns Mullin says his book had been ‘helpfully denounced’ a few years earlier. ‘Since that time I have realised that, when it comes to selling books, a good high-profile denunciation is worth half a dozen friendly reviews and I have always done my best to organise one,’ Mullin wrote.15 Times reviewer Martin Cropper said that A Very British Coup was ‘Television drama in love with television. Its title hardly encourages one to pursue the plot in search of surprises and Alan Plater’s script is the dullest he has produced in years.’16 It’s a curious observation because, far from being predictable, there’s an ambiguity even to the title of the drama, and there are numerous moments where things pan out very differently from the way the viewer expects. When journalist Fred Thompson is released from prison he seems the perfect choice – before we learn that he’s a journalist who was jailed for refusing to reveal his sources – to help engage in dirty work against Perkins, especially as he is played by Keith Allen, an actor whom Plater describes as ‘always having an air of danger about him’.17 In the novel, Thompson hasn’t been inside. The idea was suggested to Plater by events a few years earlier at GCHQ, Cheltenham. He also thought that Thompson emerging from prison, to be greeted by his posh girlfriend Liz (Christine Kavanagh) supplied a strong image.

A Very British Coup juxtaposes contrasting scenes to great effect. A scene of the UK in a power cut gives way to the newspaper proprietor (Philip Madoc) on his lilo in a sunshine retreat, manipulating the way the story back home is reported. When the power cuts look as if they are about to destroy the Perkins government we cut back and forth between a despondent Harry and his finest hour, the triumphal parade which is brilliantly lit in almost washed-out colours, as if emphasising that this moment belongs to some never-to-be-recovered, perfect past. There are lot of what Plater calls ‘cinematic wheezes’18, such as the way the camera pans out from the view of the BBC reporter covering Perkins’ election victory to show journalists (including one from the USSR) covering the event in half a dozen languages, revealing the global magnitude of the event.

The biggest and most cinematic moments also include fascinating, small details. As an awestruck nation watches a nuclear warhead being dismantled, white doves are released against the black background of the night sky and barbed wire. The reflection of this image is then seen through the eyes of people gazing into a television shop window. And even the vision mixer in the television studio has finally stopped her knitting, so that she can give the events on screen her full attention. When Thompson uses a blackboard to explain the web of deceit which is being created around Harry, his chalk marks begin to look like a Masonic symbol.

The Americans figure strongly among the villains of the piece. Plater says that Britain has been in their back pockets since the Second World War and that ‘the forelock-tugging habit is hard to shed’. He admires the stance that Harold Wilson (who as British Prime Minister was allegedly investigated by MI5 in the 1960s) took against the Americans, refusing to send troops to Vietnam.19 A Very British Coup won an Emmy in the U.S. to stand alongside the BAFTA award it picked up for best drama series, and the American press took it on the chin, acknowledging that it was a fine piece of work. The Blade Toledo said that, U.S. bashing or not, it was very entertaining, while admitting that ‘a few items might prickle the sensitivities of some American viewers.’20 Graham Fuller tacitly acknowledged the American stranglehold on British politics when he commented: ‘Thatcher’s permanent revolution has virtually dismantled the system whereby a socialist government could rule in Britain or secede from the U.S.’21 Another review felt that the serial represented an impressive change from the cosiness of much British drama – ‘about a conspiracy to overthrow the PM of England (sic) which would send your eyeballs spinning’.22

John J. O’Connor also opted to be generous despite the anti-American element, commenting that A Very British Coup is ‘certain to knock a good many Reagan-Thatcher noses out of joint but the production is so remarkably good…. that pouting would be pointless’.23 Everybody was bowled over by Irish actor Ray McAnally as Harry and the New York Times described his performance as ‘extraordinary’ when it was shown on Channel 13’s Masterpiece Theatre slot. The show was hosted by Alistair Cooke, who reassured viewers that ‘this has never happened’.24 In Australia, Robert Cockburn saw some historical parallels in the way Perkins was chewed up by the Establishment. He said that it was good for Plater that the drama was to be screened on November 9, so close to the day (November 11) when two Australian mavericks were destroyed, Gough Whitlam and Ned Kelly.25

The UK’s right-wing political weekly, The Spectator, chose not to review A Very British Coup at all, but its left-wing cousin, New Statesman and Society, gave it coverage over two issues. Nick Kimberley said that it was observed with humour and breathless pace, including a sardonic sense of Britain’s love for social display. He wrote of the ‘media-saturated environment’26, in which the Perkins government has its brief life, an observation that is even more pertinent today. The following week, a New Statesman editorial speculated about whether Harry Perkins was the best leader Labour would never have, and suggested that he was the sort of man who Tony Benn would like to have been. The leader writer reckoned that the drama gave the UK’s centre ground, the Social Democratic Party and the Liberals, the most to grumble about. “How can they appeal to the shires if it looks as though they might be contributing to letting in Harry Perkins.”27

Perhaps Glenys Kinnock put her finger on Coup’s appeal when she said that it succeeded in ‘depicting what people of all political persuasions know to be real about British politics and what people of all persuasions who believe in elected government hope is unreal.’28 In other words, people of every political hue could take something from it.

With everyone out to get Perkins, he cannot possibly win. Plater tells the story of Aneurin Bevan who was fond of saying that, as he rose up the political ladder, from councils and trades union groups in South Wales to Parliament and, ultimately, the Cabinet, he always thought he was getting to the hub but admitted that he ‘never found the power’.29 In the end, that’s Harry Perkins’ tragedy.

Originally posted: 17 October 2009.

John Wheatcroft is the author of Here in the Cull Valley, which is available from Stairwell Books here

Hi John, fantastic article. Do you have an idea of where one can read the scripts? Is it only the Hull archive?