by DAVID ROLINSON

Play for Today Writer: Colin Welland; Producer: Kenith Trodd; Director: Roy Battersby

This essay continues from Part 2 and Part 1.

The debate

Producer Kenith Trodd faced criticism and praise from local workers, employers and critics in an edition of the discussion programme series In Vision (1974-75) that was dedicated to Leeds – United!1 The play had a largely female cast who were positioned as participants: its lead actors and its extras were social actors, as mass crowds reconstructed their real-life participation in the 1970 events. The guests on In Vision include women workers who respond to the techniques by which their experiences were depicted by that male-authored text. There is a revealing tension between the play and the discussion programme. Women are addressed variously as subjects, participants and audiences, and this problematic movement is one with which the women workers are partly complicit, as we shall see. Women are the minority – 3 out of 10 guests – and are addressed in part as audience members, albeit in order to comment on the textual representation of their social participation. The programme opens up gendered discourse relating to the workplace and drama, or even contributes to that discourse. Of course, In Vision is a different type of text, with its own codes and conventions as well as its own guidelines on issues such as balance.

In Vision is part of my ongoing wider research into feedback discussion programmes. Feedback programmes are an underexplored part of the history and critical analysis of television drama: they have intervened in key debates on areas such as authorship, form and genre and have provided a space for institutional narratives on commissioning, production, censorship and broadcasting regulation and, at times, the interrogation of those narratives. My main interest is in feedback programmes made in response to docudramas. These programmes discuss or mediate the discussion of docudrama methods, their content, and even their banning. They are often made alongside those docudramas or are deal-breakers in the making and scheduling of them. Broadcasters are required to observe “due impartiality”, as the Ofcom Broadcasting Code states, “within a programme or series of programmes” – for example, by accepting that a drama may have a partial point of view but that this can be balanced by “a debate about [that] drama”.2 The regulations and guidelines on the subject are beyond my scope in this current essay, so I will let Alan Plater give a typically elegant summary, from his response to the BBC’s request for extra material during the difficulties faced by his Horizon docudrama The Black Pool: an “after the- programme studio discussion” was for Plater evidence of “the age-old BBC premise that you can get away with most things if you discuss them afterwards in a ‘balanced’ way.”3 The fact that Leeds United! was allocated such a discussion is hardly surprising given the BBC’s strong reservations about its perceived political partiality, as we shall see.

Feedback programmes take several forms, including one-offs responding to individual programmes and branded as off-shoots of them, such as Dirty War: Your Questions Answered and Shoot to Kill: The Issues. They also include series, such as Channel 4’s Right to Reply and The TV Show, and sections of arts/discussion programmes. In Vision was a BBC2 discussion programme that ran between 1974 and 1975. It covered, according to one BBC document, “a broad spectrum of broadcasting, from individual programme criticism” – which is obviously my focus here – to author profiles and interviews.4 Topics covered included audience research, broadcasting in Northern Ireland, the televising of a Cup Final, documentary, the police in television drama and American Television; and programmes featured – often with their cast and makers in the studio – included Z Cars, Barlow, Gangsters and Monty Python.

Presented by William Hardcastle, the Leeds United! episode featured the following guests, reading screen left to screen right: along the back row, John Elliott (Financial Times industrial editor), Martin Frankel (MD of Montague Burton Manufacturing), Harry Yates (National Union of Tailors and Garment Workers), Roland Hebden (clothing worker) and Mildred Crossley (clothing worker); along the front row, Barrie Farnill (Yorkshire Post), Russell Davies (The Observer), Kenith Trodd (producer), Alice Knowles (clothing worker) and Gertie Roche (clothing worker). I mentioned earlier that only 3 out of 10 guests were women, but they are the majority in terms of the clothing worker guests – 3 out of 4 – collected on the (screen) right. The three journalists are collected on the left, and Trodd is central, as the programme’s only representative. (John Hill has demonstrated that the BBC did not want Roy Battersby involved in the programme.5 ) There is no Communist Party guest to reply to criticisms made in the play, as Stewart Lane noted in the Morning Star: “Despite the Communist Party requesting that one of the Communist leaders in the […strike…] be invited to the discussion”. Lane argued that this “omission” was “particularly blatant” and that, given the statistics on Communist involvement mentioned earlier, such a guest “would have injected factual reality”.6

The fact that the employer and the union representative sit side-by-side seems loaded given that political context, the play’s analysis. Indeed, they form a line with the industrial editor of the Financial Times who presents a dominant official view of strikes. As I say this, I realise that I’m in danger of reading studio space reductively in baldly ideological terms. After all, the positioning of guests in this episode is partly the result of the code that it shares with many feedback programmes, addressing answers and comments to the mediating questioner – but In Vision‘s blocking makes for an awkward use of space. One common arrangement for such discussions can be seen in Shoot to Kill: The Issues, a 1990 discussion programme following Shoot to Kill, Peter Kosminsky’s docudrama about the killings of ‘terrorist’ suspects in Northern Ireland.7 There, the form is more clearly adversarial: two panels of guests in ideological and visual opposition. Filmmaker Kosminsky is on the same side as an Amnesty representative and the Republican Seamus Mallin from the SDLP. They are positioned at a desk on the (screen) left. Meanwhile, at a separate desk on the right sit a Conservative MP and the Unionist MP David Trimble of the UUP. Presenter Olivia O’ Leary is in the centre, the fulcrum to whom questions, answers and statements about others in the studio are addressed. There are of course practical reasons for this use of studio space – as with comedy panel shows, the visual grammar supports the use of a small number of cameras to get group and single shots for each “side”, shots which camera operators can find while the fulcrum presenter speaks to, and motivates a throw to, a specific guest. It might be crass to make a party-political reading of the guests’ positioning on the “left” and “right”, but the assumed sympathies between and against specific groups are clearly marked. Awkwardly, the In Vision guests are all positioned frontally in rows of seats, looking out at us and across to the presenter on the right. We shouldn’t essentialise studio space in either of the examples I’ve discussed, even though Trodd is positioned centrally and the discussion flows from his actions while the women are relatively marginalised at the end. But the questions, and their organisation, do offer support for that sort of reading.

Just as Shoot to Kill: the Issues opens with a question not about its allegations but about the appropriateness of docudrama, so this In Vision discussion ends on docudrama and starts with questions about the cinematic qualities of Leeds United! and how we define terms like film, play, big screen and small screen. Hardcastle presents his personal, taste-laden, praise for the achievement. Trodd explains why they fought to shoot the play in black and white and, in keeping with the references presented earlier in this essay, mentions as influences Portecorvo, Pabst and Eisenstein. Docudrama and cinematic influences were two active frames for discussion within the BBC and in press coverage; Sean Day-Lewis wondered whether they acted in opposition: “The snowball effect of the strike, workers constantly leaving their benches to join the passing marchers, looked a good deal more filmic than realistic.”8 If they acted in opposition, it might seem strange that the BBC’s Board of Governors were concerned about the play’s supposed documentary rhetoric, as John Hill noted: “it does not attempt to maintain a consistent simulation of documentary style but employs a range of film-making techniques. Indeed, […it] signal[s] its departure from documentary from the very outset” in the opening sequence’s “homage to Pabst”.9 As we shall see, a mixture of styles created other objections. But if the opening of Leeds United! uses those cinematic influences to prioritise female experience and agency, the start of In Vision does not.

It is 13 minutes before In Vision asks a question of a female guest. The three women mostly speak about their horror at the play’s depiction of women workers swearing. Given that Gertie Roche was publicly associated with the real-life strike, it is striking that she is encouraged to address swearing rather than the political aspects of the depiction. Roche was the subject of profiles, for instance in the Daily Mirror (another source called her the “quiet leader of the rag trade wildcats”10 ), and commented in public, for instance in a letter published in the Yorkshire Evening Post explaining that “The revolt is due, not to a handful of left wingers, but to something far deeper – 20 years of neglect by the employers.”11 (It seems appropriate therefore that the play was praised by Shaun Usher as “skilful, uncondescending, and […] probably quite valuable” because it leaves “no excuse for innocents who believe that workers really go on strike over a cup of tea or a rude word.”12 ) Roche, according to Katrina Honeyman, “played a critical role”, raising the “lack of communication between bosses and workers and between the workers themselves” and the observation that “there is a tremendous revolt against the NUTGW”. Roche “hoped to see a new-deal charter for the industry upon the settlement of the strike.”13

On In Vision, Roche praises Leeds United! – “I thought the play was absolutely terrific, and depicted what really happened”. Although she is critical of the play’s use of swearing, she intriguingly discusses it in comparison with Serpico in order to see the swearing as a creative device that helps to evoke “the frustrations and fury that the women felt at the time”. This is a lovely reversal from Leeds United! – now the worker is empathising with the filmmaker’s experience. Gertie later interrupts debates on swearing to reconnect it to content: although a lot has been said “on the obscene language that was used”, “what’s failed to be realised is the obscenity of people having to work in these awful sweatshops.” Like Gertie, Dennis Potter found it “insulting” that In Vision “spent most of its time discussing not the relevance, not the discoveries, not the insights of the play but its mere documentary ‘accuracy’.” Potter related this to the statement of a “wasteland orator” during the play: “The trouble is, you’re trying to ride two ‘orses with one arse”.14 The question of whether Leeds United! was “true” is asked in various ways in the programme: for example, Hardcastle presents two comparisons between news coverage from the real events and the reconstructions shown in the play. Some of the press coverage had similar concerns: “How far the reconstruction was exactly true you could not tell. The collapse of one factory into the strike was disappointingly skimped after all the confidence of its boss that he could keep it into production. And in times when two marchers usually bring three policemen the Law was oddly absent, save in one incident with scabs at a gate.”15

The discussion programme does get onto substantive issues. The women reject the employer’s assurance that sweatshops have gone, and Trodd takes up their position and states it more forcefully. They also discuss the view, as represented by the Morning Star earlier in this essay, that the strike, despite its overall failure, led to improved conditions. But the women and their politics are not the focal point of the discussion. Indeed, Elliott says that he wanted to know what the women strikers’ husbands thought during the events shown in the play. It is striking that Leeds United!, as John Hill noted, “keeps the number of domestic scenes to a minimum in order to highlight actions in the public sphere”.16 During In Vision, Trodd points out that domestic scenes were planned but, during the process of paring down the script, those scenes were removed. This prioritisation of workplaces over domestic spaces is interesting in terms of the foregrounding of work and politics discussed earlier in this essay. One of the play’s few movements into the domestic space operates as a critique: noting the “struggles to invest the CP shop steward’s treachery with political and psychological plausibility”, Hill argues that the play’s “analysis of the strike’s collapse depends […] on the insertion of a dramatically unconvincing scene at the official’s home in which he denounces the women strikers as ‘animals’ to his wife.”17 For Potter, the domestic could have enhanced the political: “as march dissolved into march, meeting into meeting, I longed all the more for a domestic sequence where the hope and then the demoralisation and sense of betrayal could really come home to roost”.18 Therefore, although Elliott’s point about the women’s husbands risked a problematic gendered shifting of agency, the play between public and private spaces was, for critics before and since, central to the play’s effectiveness.

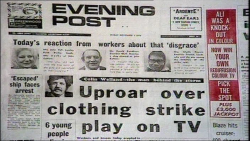

When In Vision asks the question “Did you recognize yourself?”, it is addressed not to the women but to Yates. There is a point during the discussion at which Hardcastle stops Frankel with the exhortation to “let the lady speak”, but this is something that Leeds United! does not need to say. Parallels suggest themselves between the ways in which the women workers are positioned: by their bosses (within and outwith the play), by the male authors representing them, and by In Vision’s viewer-response address. However, this is problematised by the ways in which women position *themselves* in terms of social performance. In Vision’s long discussion of swearing is justifiable in that it reflects the complaints made by women workers in the local and national press coverage of the play. The swearing was seized upon by the play’s opponents – the Clothing Manufacturers’ Federation spokesman pointed out that “There will be thousands of angry women at this portrayal of them as foul-mouthed harridans.”19 Such “angry women” feature in press pieces referenced by In Vision, and in a Daily Mail piece that this essay will use as an indicative example: ‘We’re ladies in Leeds and the BBC better believe it!’ The story reported a petition at Larlo’s factory, which stated: “We were misrepresented. We are normal, respectable hard-working women.” One woman presser stressed that “the language is no worse in the rag trade than in any other factory. It’s not right that the girls should be degraded. They are a nice bunch of proud, clean women.” Other speakers stated that “I don’t swear – ever. We are not crude” and that “When we have a works outing we never allow a man to come along. I drink tonic water in a hotel.” The female worker who organised the petition stated that “we were bugged. We didn’t know we were being taped for the first 20 minutes. It was wrong.” A male factory manager alleged that “We were told to lay the language on, to make it tougher than normal.” The use of recording equipment sheds light on one of the play’s docudrama devices and the verification of documentation. Rejecting the accusations, Welland stated that

We hung a big microphone over the workbenches because I wanted to pick up the quality of the intonation of the speech in the factory. It was no secret. Within minutes everyone knew the microphone was there. The language in the play was an accurate portrayal of the way ordinary people speak.20

Given such accusations and denials, it is understandable that In Vision asks Trodd such a direct question about swearing as “Is it true?” In 2006, Roy Battersby tried to reconcile women workers’ complaints about misrepresentation with his experience of walking across a factory floor: “the first voice I heard was a woman on a machine saying, ‘by ‘eck, I wouldn’t mind his balls banging against me bum” and fifty variations on the same which left him a sweating wreck. He was therefore puzzled by newspaper comments from workers including women they knew from making the play, and so he went to see them: according to Battersby they said that those comments had been “just for the old man”, in that they didn’t want their husbands to know what they were like at work.21 (I must stress that this was not said directly about the people quoted in the Daily Mail piece above!) Clearly complaints about swearing have wider issues of representation and identity at stake: as one worker told the Daily Mail, “My husband was annoyed. It is the association of the use of bad language with loose morals. In our case this couldn’t be further from the truth.”22 Models of feminine conduct, already loaded in terms of gendered discourse and popular representations of second wave feminism, are invoked in relation to political action, as we saw with Gridley’s dismissal of women workers as “animals” earlier.

However, and without wanting to downplay those concerns, or to give the impression that the male director’s reading of the attitudes of his subjects is definitive, an attractive if messy idea emerges: that the women were playing with social performance even while criticising the play’s performance of their earlier social performance. I’m reminded of Stella Bruzzi’s work on documentary performativity, some filmmakers’ emphasis on often hidden aspects of performance. For Bruzzi, Dineen’s work such as Geri (about Geri Halliwell) shows how the personal, individual woman’s voice has traditionally been marked as ‘other’ in a discourse whose voice (voice-over and the “voice” of documentary) is often male. In Geri, Dineen “performs an archetypal femininity” according to Bruzzi;23 for John Ellis, his students’ scepticism about Halliwell’s sincerity raise questions about how we read performance: “another identity which lies, inaccessibly, behind the performance […] performance as exactly the essence of her identity”.24 If Geri questions whether it can find the real person under the celebrity performance, it also shows that documentary itself is subject to modes of performance. Bruzzi observes the visibility of codes and negotiation in Geri, which sheds light on the ethical issues raised by the filmmaker-participant relationship. Geri performs, but Dineen also performs as a documentarian. A comparison can be made with Leeds United!, if we view the complaints reported in the press as the factory workers performing to gender roles that the play attempts not to restrict them to. In Vision gives no sense of this performative exchange between subjects, filmmakers and audiences, until viewed alongside the play. During Leeds United!, strikers pose for photographs, which are taken by a man. They copy his order to say “cheese”, with comic excess. They critique representations – earlier, one factory’s workers walked out when the radio news said that factory wouldn’t strike. But in this photograph they are performing, playing, conspiring – in different ways they might just be doing this across this play’s intermedial presence.

Far from being surprised by complaints about the swearing, Trodd had predicted them. In October 1973, he was reported as being “worried” that the “earlier timing” of the play (when it was still being discussed as starting at 8pm) “may cause difficulties because of some frank language in the script.” Trodd clarified that the play’s language was “not obscenity – there are no four letter words. But if we try to restrict them to the second half, after 9 p.m., it will sound very artificial.”25 However, the programme makers and critics were mindful of what seemed like more pressing opposition – some of which would come from within the BBC itself.

Radical drama?

In March 1974, Peter Fiddick observed that this “powerfully political play” was likely to cause problems since it would “evoke a high degree of commitment from Trodd and Battersby, two of the industry’s better-known political radicals.”26 As we saw earlier, the perceived personal involvement and sense of advocacy were an issue for a few reviewers. Peter Lennon saw it as a “weakness” that “the film-makers seemed to share the, no doubt justified, feeling of betrayal of the strikers” because the latter “was not convincingly demonstrated.”27 After transmission, Chris Dunkley speculated that “No doubt there are those who will point to – probably already have pointed to – this play as clear evidence of the BBC’s pinko-commie bias” as it showed “the ‘anti-social hours’ of the rag trade workers and the tedium of their jobs, quoted their appalling wages and filmed their unofficial strike meetings and marches in a way that gave them a certain glory.”28 Clive James speculated that the delay in finding a slot may have been connected with the timing of an election, since “the Tories would have screamed blue murder”.29

John Hill has recently discussed the tensions within the BBC over Leeds United! in the context of the time and the nature of radical television drama. Radical dramas tended to involve not merely critiquing the establishment but ‘canvassing […] social and political alternatives to it’, with concomitant debates on content and form, “debates about the specific artistic forms that ‘radicalism’ might assume”.30 Hill explains that definitions of radicalism, and of radical television drama’s strategies, are “not fixed but subject to historical change”, noting for example the shifting meaning of such terms pre- and post-Thatcher.31 The BBC supported pieces like Leeds United! mindful that “the bulk of television drama [is] conservative” in that it “maintained support for prevailing institutions and provided a form of ‘social cement’”.32 Even in this period such directly political plays were rare – Alasdair Milne, Director of Television Programmes, stated in 1975 that only a dozen plays out of 150 could be viewed as political – but were “some of the most expensive and prestigious dramas produced by the BBC […] capable of attracting a disproportionate amount of attention”.33 But, to return to the start of this essay, Leeds United! is an example of how radical drama was “often made, and shown, in the face of considerable opposition.”34

Hill valuably places Leeds United! in the context of other radical dramas made in the 1970s and in the challenges faced by Roy Battersby on Five Women/Some Women, which prompted exchanges about docudrama’s mixing of fact and fiction, and science programme Hit Suddenly Hit, the dispute over which prompted Head of Features Aubrey Singer to remind Battersby that “balance and impartiality” had to be observed and that “employment at the BBC did not constitute ‘an act of patronage giving freedom of the air’”.35 Such issues recurred when the BBC’s Board of Governors discussed Leeds United!, asking: “did the play… make it sufficiently clear that it was fiction and not documentary?” and “was it legitimate for playwrights to write loaded plays?” Huw Wheldon felt that there was “no deceit” and stated that he had forbidden “the use of real persons’ voices […even] when the people on the screen were acting their parts”.36 These comments explain the institutional logic underpinning the issues covered by In Vision and demonstrate that the combination of observed footage and voice-overs took place in a climate in which such techniques were under close institutional scrutiny after a number of controversies. For BBC figures quoted by Hill, the combination of fact and fiction challenged the BBC’s ability to enforce its “obligation to balance”: as the incoming Director-General, Charles Curran, argued, the sort of “political advocacy” that would be forbidden in factual programming could sneak through in drama because such programming “falls under a different technical classification in television”, something that Curran thought the BBC should no longer “assume without question”.37 This challenges the programme makers’ position that “‘balance’ did not operate within an individual programme but across the schedule and that left-wing plays could, therefore, be seen to ‘balance’ the overwhelmingly conservative character of the majority of TV programmes.” Hill quotes discussions about the BBC’s responsibilities to avoid exacerbating tensions at a time of industrial tensions – delays meant that the play was broadcast after 1974’s two elections, the first of which saw a confrontation with the NUM in effect bring down a Conservative government. This need not involve banning such a programme but there is a sense in the discussion that such pieces should be made less frequently. Discussing “dramatic work of a politically or socially tendentious nature”, Milne felt that the BBC should provide space for “people of genuine talent” like Ken Loach and Tony Garnett, whom he distinguished from “less talented but more obstreperous” people. Hill comments that this “appeared to include the makers of Leeds United!”, on which, according to Milne, “the editorial arguments and niceties got out of hand”.38 There would arguably be consequences in terms of the provision of radical drama and the “purge” of left-wing staff that is alleged to have followed.39 Later, Trodd, who described Leeds United! as “probably the most radical piece I was associated with”, put it in context:

…we’re dealing here with a period when there was a Labour government […] who were increasingly uneasy about the BBC, or certain elements in the BBC. That perennial thing, that the BBC is endemically lefty – I’ve never been able to make up my mind about that really. I certainly didn’t feel that the antagonisms I was involved in at the BBC were political on that narrow basis. But nevertheless there was that perception. And around 1976 – 2 or 3 years after Leeds United! – they tried a purge.40

Alleged concerns about the active WRP member Roy Battersby – such as the allegation that MI5 objected to Battersby’s use on plays like Leeds United! – help to explain his absence for the next decade.41

Such institutional debates are particularly striking given reviewer Clive James’s claim that “while it retains the capacity to commission and screen a play as serious as this, the BBC is in a solid moral position, and would be justified in asking for the licence fee to be doubled.”42 Although my essay has shown that there was some critical dissent, there were also many tributes. Despite reservations expressed elsewhere, Peter Lennon said it was “expertly filmed by Peter Bartlett, intelligently and sensitively cut by Don Fairservice, and with masterly direction of crowds by Roy Battersby was, in both an aesthetic and a social sense, a bold and exhilarating use of the box.”43 Although Shaun Usher felt that it was “Not a masterwork”, he thought it “a surging yet disciplined, earthy and engaged shot at the article” which blended “everything from broad humour to polemical anger and moments suspiciously close to blank verse.”44 Colin Welland received much praise from critics who were used to expecting high quality – The Times stated that “Once more this vigorous writer brought us a Play for Today that took us by the throat”.45 Critics were particularly impressed by Welland’s ability to combine the political and the personal. Leeds United! was therefore praised as “television with emotion […that] cut through the union jargon and the political cant that have left us these days apathetic to a fundamental human grievance.”46 “Welland’s great merit”, argued Clive James in The Observer, “is that he can work with precision in poster colours, sacrificing subtlety while retaining delicacy: his people can talk slogans at one another and still sound human.”47 The Guardian put it more directly: “Welland proves that it’s possible to bring drama into political analysis and make you cry.”48 The Daily Telegraph’s praise was more back-handed: “Any drama which holds the viewer gripped and emotionally involved for two hours, despite the depressingly familiar theme of industrial unrest and filming in grainy monochrome […to emphasise] the gloom of dank and crumbling backgrounds, cannot be all bad.”49 Peter Fiddick had observed at the script stage “the warmth and pace that has made Welland one of our most popular serious television writers.”50

Dennis Potter’s praise for Welland is worth quoting at length because it also attempts to add to as-yet inadequate “discussion of the claims and potentialities of TV drama”. Potter felt that Welland’s “talents are seen at their best” not in docudrama but when internal “contrary emotions, tangled yearnings, bruised expectations and comic dislocations” are “teased out in the domestic dialogue, public bar confrontations, inebriated sing-songs and slow, hesitant asides which fall between people”. This relates to Potter’s ongoing case for non-naturalistic form, which might be seen as an alternative reading of institutional resistance given his belief that “the future of the threatened single play lies not in simulated ‘drama documentary’, not in film, not in overtly ‘public issues tackled in a way that seeks deliberately to breach the wavering line between reportage and the often greater truths of ‘fiction’”. Several Play for Today pieces would be censored or banned outright in the next few years, but these included not just public-issue docudramas like Scum but also Potter’s formally very different Brimstone and Treacle). There was still institutional support – in 1980, Trodd observed that the “politically innocent” but potentially controversial Northern Ireland play Shadows on our Skin could only have been made with “the institutional force of the BBC behind us, against all the political forces ranged against us”51 – but Hill has shown, drama would operate under enhanced scrutiny.

For all his reservations about Leeds United!‘s docudrama approach, Potter accepted that it was “a brilliant piece of work”. It also seemed to exemplify the qualities of Welland’s work as described by Potter:

There is no one writing in any medium today who can so successfully use simplicity as the mask for complex truths or who demonstrates such instantly recognisable warmth and affection for his characters without squelching haplessly into those ever waiting bogs of sentimentality. […] A lively and rewarding dramatist.52

Leeds United!, described by its producer Kenith Trodd as “the film I am most proud of”,53 must rank as one of the greatest Play for Today pieces. It is simultaneously a testament to the television culture that produced it and a warning of the changes that were to come within that culture.

Thanks to: the BBC Written Archives Centre for access to documents; Ian Greaves for additional periodical research for Part 1; and the British Film Institute. Part 3 of this essay returns to my paper ‘“Did you recognize yourself”? Women workers In Vision’ given at the conference Television for Women at the University of Warwick in May 2013.

Originally posted: 1 April 2014 (Part 3).

Images taken from ‘Left of Frame’.54