by DAVID ROLINSON

This article presents some thoughts on special live episodes of soaps since 2010, in particular the editions of EastEnders and Coronation Street broadcast in February and September 2015 respectively.1 It identifies some of the ways in which the two series addressed liveness both textually and paratextually, as in their cross-platform interest in interactivity. Engaging with British television drama’s residual qualities of liveness, immediacy and intimacy, these episodes pose questions for our understanding of soap storytelling, in particular its handling of time. The following thoughts are unpolished reflections, taken from before and after a module screening, but form hopefully useful notes for others to develop, for instance in conjunction with this site’s other pieces on live drama across the decades and a forthcoming piece that will discuss soap time in more detail.

Introduction: Live!

Broadcasting EastEnders and Coronation Street live might seem like a nostalgic move, but such event episodes tell us more about the contemporary television landscape. In 2015, both were billed as commemorating anniversaries – for EastEnders, its own thirtieth and for Coronation Street, ITV’s sixtieth – but anniversaries are often ‘present-oriented’, as Matt Hills observed in relation to the branding of Doctor Who’s fiftieth anniversary in 2013, which formed ‘a BBC metonym […] exemplifying key aspects of the transitions that have occurred in the BBC’s role’.2 Calling Coronation Street’s live episode an anniversary special is moot – ITV expended little energy in commemorating their sixtieth, and Coronation Street’s own fifty-fifth anniversary would not arrive until this week (9 December 2015). More substantially, the live episodes remind us of a period in which many dramas were broadcast live, including Coronation Street, which makes its own (return to) live episodes potentially more loaded than those of EastEnders, which lacks that history. Up to the 1950s (and in some cases beyond), live drama was inherently linked with what television scholars call scarcity and ephemerality: if viewers didn’t watch a programme at a certain time on a certain day they would miss it, potentially forever.

This impression that live episodes constitute a backwards glance is seductive at a time when there is too much television for anyone to watch and, on ITV, so much soap that entire nights pass in multiple visits to Weatherfield and Emmerdale, paying off the colossal investment in infrastructure like so many dispiriting England friendlies at Wembley Stadium. The BBC this week used the perceived lack of variety in ITV’s peaktime schedule in order to stress the ‘distinctiveness’ of BBC One against ITV’s statements to the Government’s Charter Review.3 If we accept that logic, if ITV cannot vary their schedules then the schedules will vary themselves: live drama enables the space for qualities which used to be part of standard practice but were removed owing to the increased episode count, in particular rehearsal – for instance, the two weeks of rehearsal that were needed for the Coronation Street special.4 They also energise cast, crew and audience. Soaps have long played a tent-pole function in television schedules, with regular appointments to view which give broadcasters some continuity in terms of viewing figures and the potential to move them as a strategic ratings weapon. Live episodes to an extent move us out of this continuity – even when scheduled at the same time as usual, the episodes are trailed and often textually addressed as exceptions, as individual television events. However, they help to address a related issue. The erosion of live viewing to VOSDAL (by recording or by +1 channels) and catch-up services can be overstated, especially in relation to soap, but it is unsurprising that contemporary television embraces the live episodes’ textual and paratextual emphasis on watching programmes at time of broadcast,5 becoming high-profile television “events” like major sporting fixtures (whose throws to commercial breaks exhort us to come back “live“) and finals of light entertainment series such as The X Factor which gain high ratings.6 The live editions of EastEnders and Coronation Street this year saw both programmes increase their recent ratings, even though the latter partly overlapped with The Great British Bake-Off.7

Murder!

The Coronation Street episode shows that it’s difficult to talk about “liveness” given that soap opera’s live specials are pretty much death specials. The killing of convenient one-dimensional villain Callum follows in a line of murders and accidental deaths in live soaps in the 2010s. Is this evidence that the live soap might be a kind of sub-genre? Makers of EastEnders and Coronation Street’s live specials this decade have in different ways stressed that major events that result in tension and hysteria provide a narrative justification for the heightened, nervy performances that are seen as inevitable in live conditions. Liveness itself was the spectacle for the live edition of Coronation Street in 2000, but subsequent soap specials have sought to justify the shift in form through climactic revelations and actions. Like people, time behaves differently: the constant present-tense experienced by the viewers is mapped onto unfolding crises. (We’ll see that time in these programmes is not after all straightforward present tense, but the mobilisation of that tense by live drama might explain why so many of Coronation Street’s reviewers complained about the intrusions of the Meerkats in the sponsorship bumpers, as though it’s only a matter of time before one of them drops into the Rovers to help someone in search of cheaper insurance premiums.)

The 2010 live episode of Coronation Street is evidence of this mobilisation of energised performance. Set during the aftermath of a tram crashing into the Street, the episode has the energy of a disaster story.8 Throughout the week characters are rescued or, given that the week’s promotional tagline was the punning “Four Funerals and a Wedding”, not. This attempt to take a week out of the ongoing time of the continuing serial in the sense of presenting it as significant or complete in itself is not restricted to live episodes, but is a recurring part of their promotion: for instance, 2015’s special was billed as part of “Killer Week”. But what are murders and stunts for in soaps but to attract and comfort potential viewers with their non-soapness, intruding into genre and, whether billed as a ‘week’ or not, time?9 Again, we’ll see that EastEnders makes more complex use of time than this, though it will answer the question of “whodunnit” in its central murder mystery. The heightened register of live performance creates a sense of the characters suddenly behaving in an appropriate genre. Perhaps that’s why it took EastEnders Live Week for critics to notice how good Adam Woodyatt is.

How’s Adam?

I can’t mention live performance and Adam Woodyatt without becoming the last person on the internet to point out that the character Tanya Branning asked after character Ian Beale’s well-being by asking “How’s Adam?” and, unlike everyone else who has ever confused a soap character with the actor playing them, actress Jo Joyner became the instant target of memes. Some picked out Laurie Brett (playing Jane Beale)’s stunned reaction – and perhaps the relative scarcity of live television reveals itself at points like this, since the age of live drama brought with it practice in the skills of improvisation to cover on-screen disasters.10 Every contemporary live soap episode is accompanied by tweeters and reviewers repeating the same comments about only watching the live episode to see if something goes wrong, without realising that this is part of the mode of address that contemporary live drama aims for;11 indeed, some programmes, like BBC Four’s staging of The Quatermass Experiment in 2005, signpost the nerves of those making the programme and the sense that anything can happen (though the DVD release of The Quatermass Experiment seemed keen to disavow those qualities.12 It might seem surprising – at a time when critics and often television itself emphasise polish, marginalise or stigmatise the theatricality that was long seen as a glory of television drama, and misuse the term ‘cinematic’ as a superlative – that television emphasises the possibility of errors. However, this prospect makes explicit the idea of immediacy in production, reception and the interrelationship between programme and viewer: so foundational was the concept of immediacy to British television drama that, even when changes in technology and industrial practice meant that dramas were entirely recorded rather than broadcast live, some of its practices persisted (arguably in multi-camera studio recording).13 But the contemporary live drama is a massive undertaking. It is hugely expensive, requires a large crew and is usually delivered with great technical sophistication in rendering invisible some hugely difficult challenges: for instance, EastEnders Live Week was a triumph of sound mixing, minimising the differences between live and pre-recorded footage even when executing ambitious transitions. One of the reasons that the potential for mistakes is foregrounded is because productions setting themselves challenges has also become part of the process of making and discussing live programmes. The most explicit evidence of this comes in set-piece elements such as the Coronation Street tram aftermath or Bradley’s fall in the 2010 EastEnders live episode, but logistical challenges run throughout episodes.14

#Whodunnit

EastEnders Live Week began with episodes that combined the usual recorded scenes with a small number of live scenes. These raise some issues regarding time, interactivity and naturalism. 19 February brought two episodes. The first episode culminated in a live scene in which Ian confronted the person responsible for killing his daughter, Lucy. Tension is generated by the deferral, for a few agonising seconds, of the reverse-shot that will confirm their identity: his wife Jane. Actors subsequently talked about sitting backstage watching moments like this unfold, as if they themselves are now positioned as viewers (returned to the age of scarcity, unspoiled by soap gossip magazines), and this movement from recorded scenes to live scenes attends to a sense of the viewer’s present tense engagement. (Much of the paratextual discussion around live episodes is based around the audience’s sophisticated awareness of soap production – given that next week’s episodes have already been shot weeks ago, how can any revelation in a live episode be a surprise? – and so there are often details of protecting revelations with alternative endings15 or getting cast members to play such later scenes ambiguously and subsequently ‘drop in’, closer to broadcast, scenes in which characters and actors now know the truth.) These live scenes are marked as being different. They feature the on-screen graphic “#EELive”. The most common way in which captions appear on drama scenes is when they function as disclaimers, in particular marking out a “reconstruction” within a documentary; in its own way, this scene too constitutes a different sort of evidence.

The combination of live and pre-recorded material was not new – pre-filmed sequences were played into live drama by telecine, taking us elsewhere or extending the space of what we thought were live scenes in the studio, the kind of invisible fix that was also used at times in these programmes. But the #EELive graphic is also, simultaneously, an intrusion into the diegesis (a reminder that this is a television production that is happening right now), an extension of branding (like the digital on-screen graphics that blight digital channels) and part of the programme’s audience engagement. Of course, this engagement partly involved interactivity, providing a hashtag for debate on Twitter in a way that has become a convention for many programmes. This second-screen interactivity was also a feature within the programme: Himesh Patel, in character as Tamwar Masood, live-tweeted his experience of events around Ian and Jane’s wedding, and was briefly seen to be doing so during the episode; playfully, he was chided for his always-on behaviour even while the hashtag invited the audience to do the same and the chiding itself served as an acknowledgement (for those following his tweets on Twitter) of the episode’s tentative transmedia approach.16 Coronation Street’s variation on this was to provide “access all areas” that enabled the audience “to go behind the scenes LIVE as it’s happening” – although this was described as presenter Stephen Mulhern getting “in on the high-octane action” of the episode itself, this would come through other sources.17 Much of the Twitter traffic after this episode involved disappointment that the identity of Lucy’s killer had been either predictable or, given character motivation, unlikely. The discussion could continue because, later that night, there would be a flashback episode – a reconstruction of the events of Lucy’s death a year earlier. As the continuity announcer breezily spoilered, there would be twists – but there would be more than that.

Past, present, naturalism

The second episode on 19 February raises lots of issues relating to time in soap. In order to find out more about what we have just learned and are debating online in the present, the next episode will leave the present situation and go back to the past. In turn, this episode went out at 9.25pm, which disrupted the regular transmission pattern but also marked the potential for different content – its place after the watershed opened the possibility of darker content, as is indicated by the altered palette of the opening titles.18 The flashback episode opens with several breaches of EastEnders’ usual style. Lucy, her eyes closed, lays horizontally in front of a shifting background: darkness that is replaced by bare trees. What seems to be her body ascends while Lucy narrates in voice-over, recalling not only horror films or Laura in Twin Peaks (from the Beale storyline to Broadchurch and This is England ’88 a perceptible influence on contemporary British television drama) but also Sunset Boulevard, as the perspective of a corpse narrating a flashback to how it got there.

However, the angles correct themselves in a way that is both more and less naturalistic: she is alive, standing near Albert Square, and even the Hellish flames reflected in her eyes are now motivated by the lights of a passing Tube train, but the normalising of angles takes place through a speeding-up of camera movement and an emphasis on the fact that the technique has been subjectively, expressionistically, reflecting how lost Lucy was in her final few days. Such devices are common in trails – in 2015 alone Lucy, Kathy’s return and the Hallowe’en special have have been trailed in ways that signpost the horror genre and/or make use of slow-motion and subjective time – but less common in the programme itself. Less common but not unique, despite critics’ responses to Lucy’s flashback episode which seemed surprised that a soap should shift from its dominant naturalism or even that it should shift in time. In fact, soaps have long since used these elements.

1960s Coronation Street used flashbacks – for instance experienced by Elsie Tanner – and psychological expressionism, as when Florrie’s impending breakdown was signposted by the subjective distortion of dialogue on the soundtrack. Non-diegetic music, intertextuality and playfulness with time occurred in different ways: for instance, in an episode written by Jack Rosenthal (9 September 1964), Stan Ogden drives his wife Hilda and others in a Rolls Royce, in a piano-scored film sequence that features speeded-up film and angles and cuts that are reminiscent of the French New Wave.19

The foregrounding of style, for instance through constant tracking shots and devices from a range of genres, has been a particular feature of soaps since the arrival of Hollyoaks. (Hollyoaks has had a profound influence on flexi-narrative, potentially postmodern televisual style; similarly, the most explicit engagement with the postmodern format-breaking that characterised landmark series such as Moonlighting or the single play anthology can be found in the daytime soap Doctors.) In the last year, EastEnders has echoed 1960s Coronation Street in its willingness to connect with female experience through techniques that signpost subjectivity (as in the isolating compositions and noir lighting that accompanied Kat’s return to childhood institutions) or to move away from typical time and the vertical axis (when Stan Carter died, the camera moved between rooms at the Queen Vic from above, as if a soul’s point-of-view ascending and looking out for the family, a device familiar from many texts including Breaking Bad but part of a playing with space that is more common in soap than critics have observed). Coronation Street has used its live episodes to return to the subjective breakdown, as in the phasing and non-diegetic sound of gunfire that gives us an insight into soldier Gary Windass’s trauma flashback (triggered by the lights and disruption in the Street outside) in the 2010 live episode.

Returning to the 2015 EastEnders live week, at the end of the second 19 February episode we discover that Bobby killed Lucy. This revelation is particularly interesting in terms of time: at this moment we are simultaneously one year in the past (the flashback episode), very much in the present (this live moment again marked as an #EELive interruption to the recorded), further on in the night’s schedule and the narrative (this revelation from the past problematising our understanding of what we learned at the end of the previous episode, set a year ahead of this episode) and (viewing the moment again at a screening now) in the past, aware of where the Beales, and Bobby in particular, would go next. Our interaction with flashbacks is always complex in terms of time: as Maureen Turin observed in Flashbacks in Film, “within a given flashback segment, the spectator experiences the film in exactly the same way that one experiences any other segment of a fiction film, as an ongoing series of events happening to the characters in their immediate temporal experience, that is in their ‘present’.”20

However, there was a similarly complex attitude to time in the parts of the live week that were not live. The anniversary episode (earlier on 19 February) opened with an attempt at a shot-for-shot remake of the opening moments of the first episode of EastEnders in 1985. Then, as now, a door was kicked in and a corpse was discovered: then Reg Cox, now Nick Cotton. Those television academics who talk about narrative complexity in long-form drama but study only contemporary American television are missing a trick. This moment is not merely nostalgic homage but part of the playing-out of three decades of narrative: Cox was killed by Nick Cotton and Nick has been allowed to die by his mother Dot in the bleak culmination of cycles of (his) betrayal and (her) forgiveness. It is certainly also in the register of anniversary specials: the 2000 Coronation Street special opened with children playing near the corner shop, echoing the start of the first episode in 1960 not only in narrative but in form as this episode – live as in the 1960s – opens with black and white images and a degraded archive film effect. Seamlessly this treatment gives way to colour, and it is more clear that we are on the Street location and not, as in the 1960 episode, in the studio. The Doctor Who anniversary special ‘The Day of the Doctor’ in 2013 did something very similar – riffing on the 1963 title sequence and starting with black-and-white images of a policeman near gates marked ‘I.M. Foreman’ and taking us to Coal Hill School, but in the process moving to colour (within this 3D, globally-simulcast extravaganza). As Hills has shown, such a moment is not primarily nostalgic but present-facing and not just textual but paratextual (reinforcing the longevity of the brand, its value to the BBC and the celebratory paratexts such as the ExCel Celebration at which fans enter via such gates).

Climax

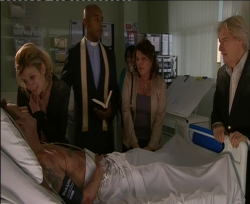

Although the first back-to-live soap episode of the century – the 2000 Coronation Street – ended not with a bang but a Ken Barlow speech reaffirming the programme’s enduring values via the device of saving its cobbles, subsequent specials have headed toward event climaxes, in particular deaths and major revelations. Coronation Street raised the stakes in 2010, with various characters struggling for survival and Peter Barlow facing the last rites (gathering the present-day Barlows in one room just as the 1960 episode did, though there the only thing in need of treatment was brother David’s bike). In the 2015 Coronation Street special, when Callum’s corpse ends up supporting Gail’s house, we’re reminded of the stink that continues to waft from the Jordache family’s patio in Brookside. Perhaps this is just a sign of the wearily derivative approach taken by the 2015 Coronation Street live special, and the series’ problems over the last couple of years; like Callum, Coronation Street is in a pretty bad place (like EastEnders in 2005, which was in a catastrophic state even before the cellar of the Queen Vic was used for similar purposes to Gail’s house). My concern isn’t so much the effect on narrative (the snobbery about melodrama that contributed to the early academic neglect of soaps) or on characterisation (though it is difficult for Coronation Street to deploy the observational delights that have often made this the best of all soaps when virtually every character is related to a murderer or victim), but physical and genre space: at what point do domestic spaces start and cease to be crime scenes rather than domestic spaces, and is it possible to remain in the same genre when its markers are displaced or haunted?21 But then, as I was reminded during the superb EastEnders: Back To Ours in which Adam Woodyatt seeks out a picture of Anna Wing (as Lou Beale) in his set/Ian’s house, soap rooms are anyway constantly haunted spaces.

This year’s fully live EastEnders episode contained a few shocks preserved for the night – not least the revelation that Kathy Beale was herself (a)live – but the focus was on the emotional fallout of the revelation of Lucy’s killer. The episode is a showcase for the qualities of live drama, multi-camera studio drama and soap opera, three areas that tend to be excluded from contemporary definitions of ‘quality’ television. Building on the qualities of liveness, immediacy and intimacy that are three of the defining characteristics of live drama – and, arguably, of British television drama – this was a tightly-focused, emotional and superbly-performed piece. The episode ended with a diegetic celebration (as the remake of The Quatermass Experiment showed, gathering actors together in one space can form a celebration for characters and actors alike, having got through that one-off event). Graffiti paid homage to past characters (Arthur Fowler via his bench) and crew (graffiti uniting the creators and incendiary producer/script editor combo Julia Smith and Tony Holland), but these kisses to the past made needlessly explicit the approach to the whole week. As a superb live mix yielded to making the fireworks the ‘duff-duff’ into the end credits, it was clear that EastEnders is currenytly in a good place; unlike in 2005, there is a clear sense of a production team that both knows how to make soap and wants to.

Time again behaves differently here – soap has long been seen as part of a belief that television is characterised by ‘flow’, following Raymond Williams’s observation (while admittedly jetlagged in a hotel in Miami and responding to American television) that programmes, commercials, trailers, films all come to form “a single irresponsible flow of images and feelings”,22 which has been taken to mean potentially reducing all experience to the lowest common denominator unless programme makers can find a form (for instance, non-naturalistic form) to break that tendency.23 Soaps have been discussed in terms of ceaseless flow – Coronation Street is, to date, an unending fifty-five year narrative – but that’s not necessarily how we experience them. Flow is a problematic enough concept – “segmentation without closure” has been suggested as an alternative given that texts do end even if television doesn’t24 – but even if the ending of soap plots dovetail with other plots at different stages, I do think that there are distinct beginnings and endings in soap. My favourite example from my own memory of original transmission is the arrival of Grant and Phil Mitchell in EastEnders, which is textually and paratextually marked as the start of a new phase, but anniversary episodes attempt their own demarcation. As Mick Carter and Ian Beale bump into each other and insist (more to us than each other, since we have knowledge that the other character does not) that they will get through their recent problems, and the narrative stops for the firework celebration, we experience a feature of seriality: as Amy Holdsworth observed, endings and beginnings can be “privileged spaces for reflection and remembering” even if an overall narrative continues.25

This sense of live episodes as “milestone moments”26 taken out of the regular time of a soap is heightened by broadcasters’ own anchoring paratexts. The 2015 EastEnders live episode was followed by EastEnders Backstage Live, both immediately on BBC One and later on BBC Three. The BBC One edition was particularly interesting, launching us immediately into Albert Square and addressing the actors. This is an instant change of register, as if Zoe Ball is a post-match reporter going onto the pitch to interview the players, and now we are not addressing Ian Beale but Adam Woodyatt (no wonder Jo Joyner got confused). The aftershow is another recurring feature of the twenty-first-century live drama – see also EastEnders Live: The Aftermath in 2010.27 Backstage Live is an extension of BBC branding – the phrase ‘a BBC Events Production’ causing alarm for anyone who witnessed the Doctor Who Afterparty – which affirms this as a televisual moment that is happening (and must be experienced) now, and stops soap time to congratulate the performers. We celebrate the successful completion of a complex live production but also celebrate soap – too often, still, neglected – and, for a moment, television.

Originally posted: 12 December 2015.

Updated:

21 December 2015: added link to The Quatermass Experiment DVD release article reference; added 1964 Coronation Street image and made minor alteration to text around it.