by JOHN WHEATCROFT

Play for Today Writer: Alan Sharp; Director: Philip Saville; Producer: Irene Shubik

‘Everybody’s in showbiz, everybody’s a star…’1

This lyric, from the Kinks song ‘Celluloid Heroes’ written by Ray Davies, conjures up a world far removed from the gloomy hall inhabited by Pete, the long distance piano player he portrays in Alan Sharp’s Play for Today. However, the play and the song (written two years later) are closer in theme than you might think. While ‘Celluloid Heroes’ celebrates the enduring screen image of Hollywood stars, it’s also about the way the film industry exploits and sometimes destroys these icons.

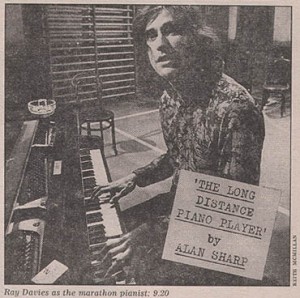

Pianist Pete is a man ripe for exploitation and destruction by his predatory manager, Jack (Norman Rossington). He plays a young man trying to create a world record for non-stop piano playing, of four days and four nights. Success, Jack constantly reassures Pete in his bogus American accent, will bring fame and fortune on an epic, Hollywood scale. However, one image of the film industry which is likely to spring to the viewer’s mind is They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? (1969), Sidney Pollack’s recent film about a six-day dance marathon in Depression-era America. Alan Sharp acknowledged his debt: ‘I read the book years ago, and was fascinated,’ he admitted in the week the play was aired on BBC12.

Pete is torn between his wife, Ruth (Lois Daine), who begs him to stop playing, and Jack, who eggs him on mercilessly towards his final goal. It’s the classic good versus evil struggle for one man’s soul, as well as a metaphor for the way we live. This aspect of the play impressed its producer, Irene Shubik, who wrote later: ‘The young man’s futile pursuit obviously represented the monotonous routine of most people’s lives’3.

This is precisely the way in which medallion man Jack tries to sell the marathon to Pete: ‘Their [the public] lives are small, they want something big.’ Initially, Jack’s interventions are quite amusing. When he says the idea ‘has bigness’, he is mangling the English language in a way that the Hollywood moguls he presumably admires have done. He talks of Pete being ‘like a fighter before his big fight’ and makes a less-than-scientific comparison between the task Pete faces and climbing Everest. At the same time, the viewer is left under no illusions about Pete’s challenge. We often glimpse him over the top of the piano, as though he is putting his head above the parapet to face an insurmountable obstacle.

His wife, in contrast, can lie on the bed or walk the streets. Ruth, however, has a strange kind of freedom. Her total devotion to Pete means that she is as much a prisoner as she is. Seeking some release, she walks aimlessly to a gloomy urban backdrop of wet streets, railway lines and aerial views of terraced-house rooftops. These are show at almost Expressionistically skewed angles, to provide a sense of foreboding over what the next couple of days will bring. At one point Ruth looks through a window and sees a girl practising her piano scales. It’s a brutal reminder that her thoughts remain with Pete.

Unfortunately, much of the dialogue that Shubik finds moving is merely banal. The close relationship between husband and wife is unconvincingly written – why does she keep asking him if he loves her? – and Davies is given an impossible task when he constantly has to talk about the fox which he saw ‘just the once,’ when playing with a now-dead childhood friend.

Davies’s performance inevitably came in for a lot of scrutiny. The Kinks’ front man and songwriter was cast at the start of an era in which rock and pop stars were increasingly making forays into acting. One argument against their use was that they were no more likely to be equipped to act than the next man or woman in the street. The opposing view was that, as professional performers, they could bring something new to a role. Director Nicolas Roeg, who coaxed more out of Mick Jagger in Performance (1970) that year than Tony Richardson had managed in the universally-panned Ned Kelly (1970) took this stance. Roeg, who later cast Art Garfunkel and David Bowie in major roles, commented: ‘Acting schools have turned out too many competent people and competence means that inspiration can get lost… I think rock stars see their performance in a different way’4.

Ray Davies doesn’t perform too badly in The Long Distance Piano Player. He under-acts, occasionally to the point of not acting at all, but never looks uncomfortable. One interesting aspect of the play was that, as late as 1970, TV drama could still look like a new medium, with actors declaiming and charging around the set as if they were on stage. Davies, who has made the occasional foray into acting since then, notably in Julien Temple’s Absolute Beginners (1986), told the Radio Times that he enjoyed the role of Pete, with some reservations: ‘I would have preferred it all to be filmed. About 90 per cent of it was done in the studios which is even harder’5. He makes no reference whatsoever to the play, or indeed any of his acting work, in his unusual autobiography written as biography, X-Ray6.

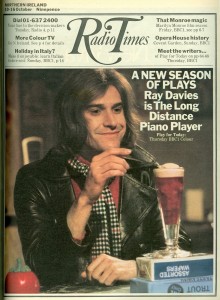

The Long Distance Piano Player was the first Play for Today to be screened by BBC1, another reason that Davies’s appearance generated so much publicity. He was on the front cover of that week’s Radio Times and generated much viewer comment. Drama always featured heavily in the readers’ letters pages in those days and viewers’ comments in October 1970 reflected widely-diverging opinions on Ray Davies as an actor. Under the headline, ‘Ray Davies, No’, one viewer wrote to say that ‘after the excruciating performance of Mrs Terri Stephens and Miss Julie Driscoll, the Drama Department would have thought twice about engaging Ray Davies.’ For another viewer, however, (‘Ray Davies, Yes’), the Kinks’ man had ‘star quality’ and ‘the face and mien of a dreamy poet’7.

Throughout the play, various actors in small parts, including a couple of snooker hall caretakers, act as a kind of chorus, commenting on the action. Some people turn up to watch, but Jack’s dreams of glory appear to have little substance about them, whether or not Pete completes his marathon. There’s no mention of alerting the Guinness Book of Records, every bit as well known then as it is now, and one suspects that this is a lack of enterprise on Jack’s part, rather than an omission by Sharp. That doesn’t prevent Jack from becoming a Svengali figure, falling out with Ruth and becoming ever more obnoxious in his attempts to keep Pete at the keyboard. Pete’s increasing desperation is indicated by his nightmarish fantasy of pushing a piano down a street. His playing becomes more eccentric and off-key, too, which excited Spectator critic Patrick Skete Catling who reckoned that he was ‘beginning to sound like Thelonious Monk’8.

Play for Today was the young sibling of, and natural heir to, The Wednesday Play which had run from 1964 until May 1970. Being the first writer up to the crease five months later for the new slot was perhaps a double-edged sword for Alan Sharp. It gave his play a higher profile. On the other hand, that meant that many viewers came to the play with extremely high expectations, forgetting that The Wednesday Play had its fair share of turkeys. ‘For heaven’s sake… couldn’t you have started off with something livelier and intrinsically more interesting,’ wrote one Radio Times reader. On the same page, another correspondent waxed positively Pooterish when he complained that the change of name to Play for Today might give the BBC an opportunity to sell viewers short: ‘The title The Wednesday Play meant quite simply that there was a new play on every Wednesday… a nothing title like Play for Today enables the planners to mess about with the placing at will. They can even drop it for a week and nobody can complain.’ The prominence given to these letters, and the 400-word reply from Shaun Sutton, Head of Drama Group, Television, showed how seriously the BBC took this part of the channel’s output, despite having, as Sutton admitted, low viewing figures compared with ‘practically any Light Entertainment show’9.

Play for Today was largely a writer-led affair, with very little fanfare attached to the role of the director. Alan Sharp, then 36, was an established novelist when Piano Player was screened but his screenplay has the feeling of someone still learning their craft. He was to become an accomplished screenwriter, most recently with the quirky Dean Spanley (2008) starring Peter O’ Toole. Sharp told the Radio Times he was a fan of television drama, as ‘it allows you to do more daring things’, but ‘it’s finished so quickly… there’s no permanence in what you’re writing’10.

Director Philip Saville was also destined to make an impact in the film world. Saville, who in 1975 was to direct the gritty Gangsters for Play for Today, went on to make the under-rated Those Glory, Glory Days (1983) for Film on Four and, in 1990, Fellow Traveller, described by Philip French as ‘One of the most politically sophisticated, visually imaginative British pictures of the past decade’11. A man with a penchant for in-your-face close-ups of people confronting one another in extremis, he creates a claustrophobic atmosphere in the hall where Pete’s record attempt is gradually falling apart.

Brian Thompson, author of the 2006 Costa Prize Biography winner Keeping Mum, subscribes to the view that this was a golden age for television drama, and that something has been lost in the intervening years. Thompson, a full-time writer, broadcaster and novelist for 40 years, made his breakthrough in the 1970s as one of the talents nurtured by Alfred Bradley, the senior drama producer for BBC North who died in 1991. Thompson says that these dramas made people think and challenged their preconceptions: ‘It was a very good time for writers. There was a moralistic element to the work of Mike Leigh, David Mercer, Arthur Hopcraft and John Hopkins. Then, television was able to create the taste by which it was going to be judged. Now, reality TV and soap operas have created a mistaken belief in many people that they understand human nature. There’s more of a cultural divide’12. Thompson sent up this ‘moralistic element’ in Our Harold, an affectionate piece broadcast on Radio 4, about a young electrician fired up with the desire for knowledge by a course at his local tech: ‘It were a bloody smashing Wednesday Play that night… about some wench who tries to drown herself on account of some communist bloke with a beard who wants to whip her ‘cos she won’t sleep with his brother, who’s like in television or summat’13.

Not everyone saw this as a golden age for TV drama, as Bernard Hollowood’s review of Piano Player makes clear in Punch magazine. He suggested that the large output of new drama on TV dwarfed the creative literary talent available. The corollary, Hollowood suggested, was that watching would always be a gamble, one which led him to ‘make allowances and accept the mediocre as better than average’. He likened the play to ‘a short story stretched out to fill a novel’ and suggested that Saville and company had to use ‘a lot of canny silence and unnecessary camera excursion as padding’. Hollowood also thought the play was badly served by the ‘succession of over-long and explicit trailers’, which gave away too much. For all that, he found the play’s ‘texture’ interesting and thought Davies and Daine were ‘convincing enough’14.

Overall, that could be read as faint praise or dismissal of the play, and Hollowood wasn’t the only critic who sat on the fence. In The Times, Chris Dunkley suggested that it would appeal to people who like a beginning, middle and an end before qualifying even this rather patronising testimonial by adding that ‘the middle was a little tedious in parts’. Dunkley has some fun with the allegedly Pinteresque nature of some of the dialogue, particularly involving the snooker men, before conceding that the production had ‘a remarkable atmosphere’, helped by the ‘damp, respectable squalor of the church hall’ and that Davies (who he described as ‘a member of The Kinks’) was ‘more than passable’15.

Skene Catling, his quips about bebop jazz aside, saw the play as being about ‘a protagonist who finally rebelled against dehumanisation when all seemed lost… and achieved metamorphosis – more symbolism of course – into a freedom-loving red fox16 of cherished memory’. He then went on to have it both ways, too, by suggesting that Piano Player was ‘well written, well directed, well photographed’ before adding ‘in its inexorably dreary way’17. He does, however, put his finger on a genuine weakness when he says that, in the end, ‘all suspense depended on a single question… would he quit before playing for four days and nights or wouldn’t he’. And as Pete falls into Ruth’s arms at the end, well before reaching his goal, you feel a fleeting relief that he’s given up, but it’s all a bit of an anti-climax.

If everybody is in showbiz, then Pete’s 15 minutes of fame have clearly come to an undistinguished end. And Jack, we can safely assume, is already in the process of digging out some other naive dupe who can help him to achieve his own vicarious form of celebrity.

Images reproduced from the Radio Times coverage of the play.

Originally posted: 4 November 2010.

[This piece first appeared on this website’s Play for Today mini-site in May 2009. It was transferred here when the Play for Today section was integrated into the main site.]

John Wheatcroft is the author of Here in the Cull Valley, which is available from Stairwell Books here

I saw The Long Distance Piano Player for the first time recently, and hadn’t realised before that it was another ex-radio play. The 1962 original would have been an interesting exercise, with a Radiophonic Workshop soundtrack of ever-more discordant piano playing.

https://genome.ch.bbc.co.uk/793a27dd5ef24c168d619ad2e79f72f7

I like its description as a parable, rather than a drama. Worth mentioning that it is the only Play For Today to survive in an edited version. The original was 80 minutes, whereas what we’ve got is only an hour. I guess that there might originally have been more discourse between the pianist and the wife, which moves forward rather suddenly – and Philip Saville speciality montage sequences of Ray Davies wandering aimlessly around town.

Pingback: Philip Saville: Play for Today Biography – British Television Drama