by DAVID ROLINSON

The opinion that Dixon of Dock Green (BBC, 1955-76) was a cosy anachronism throughout its existence, and in particular in the 1970s, remains pervasive. Lez Cooke’s excellent study of British television drama fairly summarises the common view that Dixon “gained a reputation as a ‘cosy’ representation of the police and their relationship with the public in the mid-late 1950s”, a representation which was “superseded” in the 1960s and 1970s “by more hard-hitting and up-to-date representations of both the police and the criminal underworld”.1 Dylan Cave goes further in Ealing Revisited, arguing that Dixon‘s long run “wasn’t due to innovation, but to its dogged refusal to acknowledge the pace of a changing Britain, as depicted in the far tougher police series Z Cars and The Sweeney. It was cherished as a reassuring reminder of apparently simpler, gentler times”.2 There is room to question the pervasive generalisation that 1970s Dixon was a cosy anachronism that was smashed up by the arrival of The Sweeney (ITV, 1974-78). As I’ve argued in my previous writing on police drama,3 this generalisation needs to be put under more scrutiny, either by putting The Sweeney in the context of the detailed study of other police and action series of the period (Cooke wisely uses the plural “representations”), or looking into the apparent anomaly that Dixon survived – indeed, was still hugely successful – well into the 1970s. Dixon makes its own use of the changing language of police drama – with its “shooters”, “birds” and “blags” and the prioritisation of the CID while former beat copper Dixon takes a back seat – and reflects the changing practices of, and attitudes towards, the police. Acorn Media’s welcome DVD release of six colour episodes gives me a chance to look more closely at 1970s Dixon to add this article as a supplement to this much longer and more detailed piece on Dixon’s place in the history of police drama.

There’s plenty of evidence to support Cooke’s point from the start of this article. Dixon of Dock Green’s creator, Ted Willis, summarised its changing critical reception in a piece in the TV Times in 1983:

In the first years, the critics were almost unanimous in their acclaim for Dock Green, hailing it as a breakthrough, praising its realism. But slowly, the view began to change. We were accused of being too cosy and the good word was reserved for series like No Hiding Place, Z Cars and Softly, Softly. These, in turn, were superseded by the violent, all-action type of police drama like The Sweeney, […] Strangers and Killer.4

As Cooke notes, in 1955 Dixon was distinctive in resisting “idealised” detectives in favour of “an ordinary, working-class policeman on the beat”,5 with Willis seeking to “concentrate on the smaller everyday type of crime, and put the emphasis on people rather than problems.”6 As I noted in my previous article, Willis talked in 1957 about seeking “to break away from the accepted formula for police and crime stories […] The average policeman might go through a life-time of service without being involved in one murder-case. His life is one of routine […] Would [viewers] take simple, human stories about a simple ordinary copper and the people he meets?”7 Although Willis no longer wrote for the series in the 1970s, most of the episodes in this DVD release reflect this procedural emphasis – as Willis put it in 1983, “Eighty per cent of police work is ordinary and unsensational” – albeit in a format driven more by the CID and a larger cast of characters in a setting that is closer to the markers of “toughness” in action-driven police series of the period. Without claiming to be the sole creator of Dixon or author of The Blue Lamp (1949) – due attention must be paid to Jan Read, and Willis quickly reminds us in this piece that the film’s final screenplay was written by T.E.B. Clarke – Willis was reflecting upon his research for the film, in particular Inspector Mott of Leman Street police station, who “built up a special relationship with the people he served”. “I admit that Dixon of Dock Green was sometimes too good to be true,” reflected Willis, “but, by the same token, many of the TV police characters who followed him have been too bad to be true.”8

My previous article contains some critics’ and viewers’ responses to the series. However, by adding a couple of extra pieces of press coverage from 1974 – the latest year represented in these DVD episodes – we can see that its reputation was not quite set in stone. In his side job as television critic, Dennis Potter, savaging a “pathetic” episode of Barlow as “the ultimate degeneration” of the Z Cars lineage which had previously brought “some of the best writing to British television”, noted that the early Z Cars episodes under Troy Kennedy Martin, Allan Prior and John McGrath had been successful in part because of “the startling contrast they made with Dixon of Dock Green, a cotton-wool-and-humbug series which belonged to a much earlier layer of television”. Describing George Dixon’s remarks to viewers at the end of each episode as “a uniformed imitation of a Wayside Pulpit”, Potter found it “a small miracle that his programme survived the critical disdain which came whenever comparisons with the newcomer were made.”9 Potter watched an episode of Dixon to “see if the roles had been reversed, with Dock Green the scene of street-level realism and Barlow the anserine confection”, but thought that Dixon was “just the same as ever.”10 To be fair, Potter disliked the casual use of violence in formula series, and he wrote a negative review of the postmodern, socially-concerned Gangsters, so he’s not simply critical of Dixon on the grounds of stereotypical quaintness.

By contrast, more favourable comments regarding Dixon can be found in a 1974 opinion piece by James Scott, which briefly charts police drama as part of its discussion of whether television drama was descending into “‘play safe’ attitudes”. (Incidentally, Scott begins his piece with the discontented comments of a television writer depicted in Potter’s play Only Make Believe.)11 Scott noted that Dixon “has been mauled by the critics who find it smug and unreal”, but whilst the early years of Z Cars (1962-78) “had a directness and honesty which has never been equalled far less surpassed in any police show since”, Z Cars “has declined badly over the years and now looks rather tired”. By contrast, “Many of the [Dixon] scripts have been excellent and have contained sharp and pertinent social comment.”12 Similarly, director Michael E. Briant spoke highly of his time directing Dixon in the 1970s, finding it “one of the most underrated police series”, produced by the “very shrewd and talented” Joe Waters. For Briant, Dixon was “actually very modern and compelling compared to the boring and trite Z Cars scripts of those days.”13 Indeed, Briant’s experience of directing Z Cars in the 1970s was that the scripts were “never very inspirational but very workmanlike” and that “creativity” on the part of directors was “positively discouraged”, unlike on other shows he directed such as The Newcomers and Doctor Who.14 (I recently stumbled upon a Radio Times letters page in which this same producer said “Mea culpa”, and not much more, when a former policewoman criticised Z Cars for a poor sense of protocol in the questioning of female suspects and argued that the part of women police, “a working part of every section of the police forces today”, is “very underplayed” in this and other series.)15 Scott and Briant’s comments may surprise viewers who are more familiar with the idea of Dixon as a cosy anachronism.

Scott’s comments on “pertinent social comment” are borne out by some (though admittedly not all) of the episodes on the DVD set. The episodes are scattered across several years – 1970 through to 1974 – but this is not a random selection. These are the six earliest available episodes from the colour era, rare survivors of the wiping of episodes which hit Dixon of Dock Green particularly badly. ‘Waste Land’ (written by Eric Paice) opened the seventeenth series in late 1970, and ‘Jig-Saw’ (also by Paice) opened the eighteenth series in late 1971. The other four episodes come from the twentieth series: the opening episode from late 1973, ‘Eye Witness’ (written by Derek Ingrey), and three episodes first broadcast in 1974, ‘Harry’s Back’ (written by N. J. Crisp), ‘Sounds’ (by Paice again) and ‘Firearms Were Issued’ (by Crisp again).16 My previous article looks into several half-hour 1950s episodes which, as Cooke persuasively notes, were almost “a hybrid” of recent BBC successes The Grove Family and Fabian of Scotland Yard, presenting “a comforting, reassuring image of the police”.17 Episodes moved to forty-five minutes in 1960, and the 1970s episodes are all in colour, some shot entirely on film and others mixing film location work with videotaped studio interiors.

All episodes feature one of the series’ most famous devices (referenced on the DVD cover): “Dixon’s personal address to camera at the beginning and end of each episode” which Cooke noted of the 1950s episodes, and whilst Cooke justifiably observes that these speeches “were designed to reinforce” the reassuring image of the police, we will see that their use in the 1970s episodes is sometimes less straightforward than the paternalistic reassurance we might expect.18 This is particularly the case in ‘Waste Land’, which opens with Dixon reflecting on how “most of us remain ignorant of one another”, and closes with Dixon’s tactful acknowledgement that the official version of events might not allow for human complexity.

Indeed, ‘Waste Land’ is the most striking episode on the set. Its pre-credit sequence is notably disorienting: a hand-held point-of-view sequence with heavy breathing, abrupt movement and an eye for urban decay and absurdity, such as an abandoned doorframe swinging incongruously on waste ground. Voice-over dialogue heightens the sense of dislocation with its description of a state between dreaming and waking, “looking in a mirror at a mirror”. Dixon’s voice plays over a police radio, but the way that his call to “report your position” is shot makes it unsettling and we realise that the request might not be easy to answer. The episode details the search for a missing policeman, and the point-of-view opening and concern with the distance between people recall peak Softly, Softly episodes written by Alan Plater, in particular ‘Sleeping Dogs’ (1966) and ‘Going Quietly’ (1968), and whilst the episode is not in their class, it’s worthy of that flattering association.19

As discussed in my other piece, by this stage the series’ focus is on Andy Crawford (Peter Byrne) – in these 1970 episodes, a Detective Sergeant – who had been in the show since the start, when he was assimilated into the paternalistic police family through marrying Dixon’s daughter Mary (who gets just a fleeting dialogue mention during these episodes). Now a more recognisable 1970s drama CID type, Crawford is tougher, occasionally cynical and aloof. His team of suited investigators includes Detective Constable Lauderdale (Geoffrey Adams), who I last saw in the 1960 episode ‘The Hot Seat’ on its BBC4 repeat, and who has come a long way from the elaborately-moustached posh-fish-out-of-water figure of fun he was there.20 Dixon – a Sergeant since the mid-1960s but listed in the credits simply as ‘George Dixon’ – is increasingly bound to the station, but in this episode covers a lot of ground as the investigation sets up base in the area of the disappearance.

Empty docklands, overgrown waste ground, disused spaces: in the iconography of police series these are often the sites of punch-ups and shoot-outs, but here they mark forms of isolation, the distance between people and the scepticism expressed by some locals regarding the kind of community that this series is so often seen to embody. The location work records areas that have been subsequently developed – as Guardian reviewer Tim Dowling noted, “the show seemed to sense it was part of a fast-vanishing world. Abandoned industry formed its backdrop – everything is overgrown and crumbling”.21 The same might be said of various other plays and series from this period, but the effect is worth noting: if these spaces are more unsettling than nostalgic, Dixon’s walking of these spaces plays two forms of growing obsolescence alongside each other in ways that are surprisingly troubling. As in various plays in the period, we are witnessing the end of the walkable, “knowable community”,22 even when Dixon isn’t helpfully framed in the same shot as a disused vehicle prominently but redundantly promising a ‘Warm Home’.

‘Jig-Saw’ may resolve its story of mysterious attacks on women in a way that resembles the simpler characterisations of early episodes, but even here there is a grubby, cloying desperation at work. Its repetitive scenes of a form of (in this case, entrapping) reconstruction brings to mind John Hopkins’s later Play for Today ‘A Story to Frighten the Children’, itself a police procedural of genuine interest to anyone documenting the supposed irrelevance of the Dixon “type” in the face of the likes of The Sweeney and Target (BBC, 1977-78), although A Story to Frighten the Children’s devastating opening section would be strong stuff for those series, let alone Dixon.23

Shot entirely on film, ‘Waste Land’ and ‘Jig-Saw’ showcase the work of film cameraman Phil Meheux, early in a varied and distinguished career that would include collaboration with John Mackenzie (Apaches, Dennis Potter’s Double Dare, The Long Good Friday), Alan Clarke (the film remake of Scum) and Martin Campbell, and provide a welcome link between The Killing Fields, Casino Royale, Beverley Hills Chihuahua and The Smurfs. Meheux’s photography is one of the highlights of this set. As well as capturing the more expressionistic point-of-view moments of ‘Waste Land’, Meheux provides shadowy interiors, and camerawork that is mobile, sometimes hand-held, combining the social realist capturing of landscape with a poetic isolation of detail, and a combination of movement and framing that isolates buildings, and sometimes people, in space. These techniques emphasise the sense of people in the community getting lost or struggling to connect.

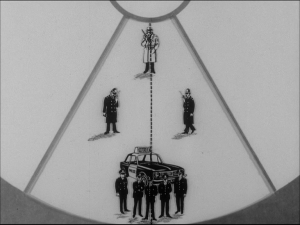

These questions of connection also map onto the programme’s relationship with developments in policing. Some potential witnesses display degrees of self-protection and cynicism, and policing has moved on from the old single-handed Dixon model, adopting technology whilst trying to retain vital personal contact, while acknowledging the limits of their reach. Dixon has been described as providing positive PR for the police – see my previous article – and strangely enough these moments of apparent weakness and the awareness of isolation might be serving a similar function, if we compare these 1970 and 1971 episodes with Central Office of Information shorts from the period, such as Unit Beat Policing (1968), in which we are told that:

The British policeman has always been the trusted guardian of law and order. This trust has been rooted in the feeling that a constable belongs to his neighbourhood and that he is a friend of everyone that lives there. They know him and help him […] In most modern towns, this relationship between public and police is less close […] the town policeman finds it difficult to know many of his people […] Much of what he has to do has little effect in the war against crime. So those natural partners, police and public, have become estranged […] without public help, effective police work in Britain is almost impossible […] conventional police work and equipment need looking at.”24

The solution proposed by the Director of Police Research and Development Branch in the film, indeed the cause which the film is pushing, is the system of Unit Beat Policing, with patches patrolled by a unit of fewer officers, a Detective Constable and modern communication equipment. The development of this system can be seen in various police dramas, as I mentioned in this piece on Yorkshire TV series Parkin’s Patch (ITV, 1969-70) which has been released on DVD by Network. While I’m reviewing DVDs that aren’t the one that I’m meant to be reviewing, the short Unit Beat Policing is on the BFI’s Police and Thieves collection of COI shorts, which include some fictionalised pieces of possible interest to this site’s readers, for instance Anything Can Happen (1973), a police recruitment film scripted by Gerry Davis and starring Simon Rouse and Jeremy Bulloch.

‘Eye Witness’ and ‘Harry’s Back’ share surface elements with the world of The Sweeney: intimidation with shooters, a moll-accompanied heavy issuing orders from a swimming pool and Crawford leaning on snouts. ‘Eye Witness’ is fairly unsophisticated and quite endearing in its naïve rural relocation in the name of witness protection, while ‘Harry’s Back’ is a pleasing character piece about a charming villain whose popularity on his home turf appals Crawford, whose hounding of Harry puts him closer to The Sweeney’s Regan than Dixon. Crawford even suffers pointed comments about his lack of promotion, always a thorny topic for critics of the plausibility of Dixon’s leads (Crawford is a Detective Inspector by the time of the set’s later episodes).

‘Sounds’ and ‘Firearms Were Issued’ have the more familiar piebald look of filmed exteriors and studio interiors, with Dixon behind the desk of a more settled Dock Green nick.25 In ‘Sounds’, the police are faced with having to trace a child who telephones after her mother is attacked, and their response proves most of the points made by the Director of Police Research and Development Branch in Unit Beat Policing, as their mobility, modern communications and attempt to engage the public help their search when allied to their local knowledge and membership of the community. However, there are twists to come.26 Where the episode falls more into the series’ primetime LE scope is the broad characterisation of the musical expert – a colourfully-outfitted and unreliably monickered27 hi-fi “technical jargon” type – called in to improve their analysis of the call. I’m a keen follower of British television drama’s incorporation of elements from Francis Ford Coppola’s The Conversation – for instance, in a pivotal sequence in Potter’s Double Dare – but perhaps this one’s a bit of a reach.

‘Firearms Were Issued’ again steps into the territory of the period’s more action-driven police series, as Crawford leads an armed raid on suspected armed robbers. However, process is still uppermost – Dixon logs out the weapons by the book in solemn detail – and when things do not go according to plan, Crawford and his colleagues find themselves under investigation. Dixon may be more often chained to his desk by this stage, but he’s serving an interesting role in the drama: Crawford’s apparent pragmatism appears to include a willingness to bend the rules, which pushes him against the straight if sympathetic Dixon. There is no escaping Jack Warner’s advancing years, the plausibility issues that are raised by his continued presence, and the contribution that his persona and undoubted appeal to older viewers made to readings (sometimes misreadings) of the series in terms of nostalgia. Indeed, Dixon’s last series was promoted in the Radio Times in terms of 72-year-old admirer May Pamment, who “collects Jack Warner press cuttings and signed photographs of Dixon [… and] several records, including a monologue of road safety advice for drivers and a 78 record of one of Warner’s wartime Cockney comedy acts in the BBC Radio Show Garrison Theatre “, though she admitted preferring his more “refined” speech in the modern series to the way that Warner, Byrne and Arthur Rigby (Sergeant Flint in earlier episodes) “had the ring of Bow Bells”.28 This Radio Times piece notes that Warner, now 80, “has been getting bee-sting treatment for an arthritic hip” but will “carry on resolutely, as long, he says, ‘as I can stand and talk, and people want to see me’.”29 Warner’s age was certainly an issue at the time, but seems to be more so now than in a media landscape which was not yet obsessed with youth: from James Bond to Doctor Who, Carry On to action series like The Sweeney and others in the wake of The French Connection and Gene Hackman’s success, leading men (sadly mainly men) were often middle-aged or older. That defence is perhaps tenuous – as we’ve just seen, Warner was playing Dixon at 80 – but Dixon’s part in the series has changed by the 1970s, and his persona has its own value in episodes like ‘Firearms Were Issued’.

In the episodes on this DVD set at least, he has adapted to social change more readily than the homily-spouting, change-resistant Dixon of the 1950s who informs critics’ perceptions of the series. When ‘Sounds’ moves into the darker area of domestic violence, the attitudes of Dixon and the programme have clearly moved on from earlier days.30 The resolution of ‘Firearms Were Issued’ veers towards my and Cooke’s comments regarding the ideological sewing-up of situations, as Dixon briskly informs us that he would have done the same as the officers in similar circumstances. Whilst there have been some interesting tensions amongst the police and between them and their investigator, and the acknowledgement of potential fallibility, there is indeed something quaint in the episode’s handling of a potentially incendiary topic – the shooting of an unarmed man – in the language of wounded naivety and chalkboard diagrams. However, the sense of Dixon’s closing speech being pat is far from the norm. Dixon’s speech to end ‘Sounds’ is bleak in its implications and appropriate to the episode’s tone. Viewers expecting a nostalgic trip back into a warm Saturday night primetime family drama might be surprised by such bleaker moments. That’s not to say that there won’t be plenty of nostalgic triggers, and plenty of enjoyable archive television faces: James Grout, Anna Karen, Victor Maddern, Windsor Davies, Glynn Edwards, Gwyneth Powell, Stephen Greif, John Salthouse, Lee Montague, Michael Sheard and of course Cyril Shaps. Those bleaker moments don’t prevent Dixon of Dock Green from being overall a lighter show which lacks some of the edges of dramas around it, and there are indeed some creaky moments in its plotting and the depiction of hardened criminals in a pre-watershed family show (although Willis’s selective list adds to the wrong impression that crime drama meant a choice between Dixon and action series, thereby omitting for instance the numerous police shows which were broadly in the Dixon register and, for that matter, shows that weren’t in either camp, such as the magisterial detective-based drama Public Eye, which got huge ratings for many years with its alliance of inventiveness, character focus, an unconventional lead and sometimes minimalist narrative).

Recalling the show’s final years, Willis noted that it continued “to hold a huge audience”, and (in keeping with Cave’s point at the start of this article) wondered whether “people tuned in to seek reassurance.”31 It was, according to Mary Whitehouse’s National Viewers and Listeners Association, the nemesis of several other programmes discussed on this site, “the most suitable programme for a family audience”.32 Willis acknowledged that this was a different world – “Words like ‘fuzz’ and ‘pigs’ were being used to describe the police” – but “Dixon was a kind of proof that the old ‘bobby’ was not dead.”33 Radio Times letters pages in the 1970s support and oppose perceptions of the decline of Z Cars – in 1973, one reader dismisses a reviewer’s belief in the superiority of Softly, Softly by calling it “a series of fairy stories with an overloaded whitewash brush for its heroes, and a surfeit of crudity substituting for realism”, and gives guarded compliments to Z Cars for not trying to “romanticise” its “heroes”.34 Another letter writer thought the Kingsley Amis episode of Softly, Softly under discussion was “a disaster”, adding that “We do not want the series to degenerate into third-rate social psychology pieces written by would-be egghead writers to ‘explore’ society.”35 It would be difficult to take this as the representative view of the entire audience or a statement about the conservatism of the genre – the counter-attack reply by the reviewer these letters were criticising suggests that they aren’t – but it sheds different light on some of the issues covered in this essay.

But we could actually take Willis’s previous point further: condemning Dixon of Dock Green for being outdated carries its own problems. James Piers Taylor has noted that a COI research report into the recruitment short Challenge for a Lifetime argued that it “concentrated too much on the exciting elements of the job and excluded the routine elements which would have provided a rounded impression”. The extent to which this sort of film needed to be “persuasive propaganda” was therefore an issue.36 The idea of Dixon of Dock Green as propaganda was an old one – see my previous article – and Arthur Ellis, the writer of the excellent satirical play The Black and Blue Lamp which interrogates the Dixon persona, noted that The Sweeney was just as much a PR exercise, with the novelty that it “romanticised screen violence, which gave the Met a nice tough little image that invariably helped them employ it”.37 As Ellis put it, Regan “supplanted” the “idea of a decent beat copper”, but Willis’s observation usefully demonstrates that, in fact and fiction, the Regan rather than the Dixon stereotype was to be underplayed by the police as they sought to restore their place in modern communities. There’s more detail on this in my other piece – in particular the thesis-antithesis-synthesis model – but there’s more than enough evidence in this DVD release that the accepted story of the violent Sweeney overturning the cosy Dixon can be problematic. Certainly Alan Plater, who was as great at police drama as he was in many other areas of drama, argued in police publication Context in 1976 that “It is just as irresponsible to portray the Police as always chasing murderers and big-time criminals as it is to show them as boy scouts like George Dixon. The Sweeney is ridiculous. It’s James Cagney and the Sundance Kid rolled into one and given an English background.”38 Dixon‘s continued focus on process and the everyday made it particularly relevant in the 1970s and 1980s: indeed, in 1983 Willis found in The Gentle Touch and Juliet Bravo distinct similarities to the earliest episodes of Dixon of Dock Green, and noted that “The police are making great efforts to re-establish their position in the community, more men are going back on the beat.” For all its flaws, Dixon continued, and continues, to play an interesting part in depictions and perceptions of policing.

Dixon of Dock Green is available now on DVD (Acorn Media). Other titles mentioned in this piece are also available: The COI Collection Volume One: Police and Thieves (British Film Institute), Public Eye, The Sweeney and Parkin’s Patch (all Network DVD).

Thanks to John Williams, Ian Greaves and Jim Smith.

Originally posted: 31 August 2012.

Updates:

5 September 2012: minor corrections and added further Radio Times quotations.

28 September 2012: added Plater quotation from Context.

8 December 2012: added Cave and Briant quotations and material from three more Radio Times letters (on women police, Softly and Amis), reworked opening paragraph.

Lopsided in The Ladykillers which Warner had recently been in, even managing to be a Superintendent there. And of course, were cops ever part of their communities as depicted at Dock Green?

Pingback: Love Will Tear Us Apart – Dreams Gathering Dust

Volume 2 now announced! –

http://www.acornmediauk.com/new/dixon-of-dock-green-collection-2.html

Includes all the surviving episodes from Series 21, although the inserts also survive for ‘Chain of Events’ (3 May 1975), though I imagine that it would be beyond the wit of Acorn to include them as an extra. The first two episodes are all-film affairs.

Pingback: The ‘Appening: Parkin’s Patch (1969-70) | British Television Drama

Hi – great to hear from you, I’m enjoying your blog. Yes, I was aware of that ep’s archive status (Kaleidoscope’s archive guides amongst other sources), so I used the Acorn word “available” rather than “existing”: my understanding was that there’s a fault with that episode, though I’ve no idea of how (in)surmountable it is. I haven’t contacted Acorn (I bought the DVD rather than request a review copy) and wasn’t writing about archive holdings (or technically writing a “review”!). That’s a shame because it meant neglecting to mention other things that a DVD could have included, like the surviving segments of otherwise “lost” episodes. See for instance the list here, which I’m sure you’re already aware of: http://www.mausoleumclubforum.org.uk/xmb/viewthread.php?tid=24447&page=1 .

“These are the six earliest available episodes from the colour era” – Not actually the case. Typically, Acorn have omitted an episode. ‘Molenzicht’ (1 January 1972, w. N.J. Crisp, d. Joe Waters) survives, presumably because its another atypical all-film edition, with extensive use of footage filmed in Holland.

Pingback: From The Blue Lamp to The Black and Blue Lamp: the police in TV drama | British Television Drama

Pingback: Recording ‘Public Eye’ (ABC) on location in Birmingham (1966) | Spaces Of Television