by DAVID ROLINSON

“in keeping with the modernist sensibility and self-reflexivity of Hide and Seek and Only Make Believe, the decision to root a view of the past in the experiences and imagination of a writer protagonist, emphasises the fact that, far from being an objective assessment, any perspective on history can only ever be subjective” – John R. Cook.1

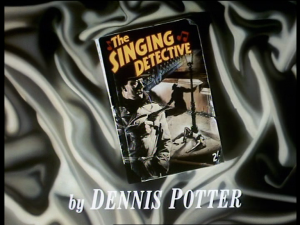

This one-day symposium, staged by Royal Holloway University of London on 10 December 2011, celebrated the 25th anniversary of The Singing Detective (1986).2 It paid tribute to the serial’s “narrative complexity, generic hybridity and formal experimentation” and placed writer Dennis Potter’s contribution alongside the contributions made by his collaborators, several of whom were present: producer Kenith Trodd, choreographer Quinny Sacks and actors Patrick Malahide and Bill Paterson.3 Other guests included Peter Bowker (as a modern television writer inspired by Potter), plus academic speakers and, mixing practitioner and academic perspectives, Professor Jonathan Powell, who was Head of Drama at the BBC when The Singing Detective was made. This mixture of academic and practitioner perspectives has been a welcome and often rewarding feature of British television drama conferences in recent years: see, for instance, the conference proceedings published as part of British Television Drama: Past, Present and Future.4

Frank Cox, who died in April 2021 at the age of 80, was a television director and producer who worked on drama at the BBC and ITV across a period of more than forty years. Although his was never a household name, he was responsible for realising some of Britain’s most popular drama series and did much to boost the position of Scottish television drama.

Frank Cox, who died in April 2021 at the age of 80, was a television director and producer who worked on drama at the BBC and ITV across a period of more than forty years. Although his was never a household name, he was responsible for realising some of Britain’s most popular drama series and did much to boost the position of Scottish television drama.