by JAMES ZBOROWSKI

Back in 2013, I did a small piece of research on visual style in Coronation Street. This was for a couple of different reasons. For a few years, I had been using Christine Geraghty’s very helpful distinction between the ‘realist’ tendencies of British soap operas in their earlier days and the shift towards melodrama that has occurred more recently, and I wanted to investigate whether this evolution might affect things like scene duration, shot scale, and so on. I have also been interested for a long time in David Bordwell’s work on visual style, particularly visual style in Hollywood cinema. Bordwell’s article ‘Intensified Continuity’ in Film Quarterly argues, convincingly, that there have been four major, interlocking changes in the visual style of contemporary American film as compared with what we might call ‘the classic era’: ‘More rapid editing’, ‘Bipolar extremes of lens lengths’, ‘More close framing in dialogue scenes’, and ‘A free-ranging camera’. I wondered if I might find similar changes at work if I compared old and new episodes of soap opera (and I decided to focus my attention on the first and third of the features Bordwell mentions).

Back in 2013, I did a small piece of research on visual style in Coronation Street. This was for a couple of different reasons. For a few years, I had been using Christine Geraghty’s very helpful distinction between the ‘realist’ tendencies of British soap operas in their earlier days and the shift towards melodrama that has occurred more recently, and I wanted to investigate whether this evolution might affect things like scene duration, shot scale, and so on. I have also been interested for a long time in David Bordwell’s work on visual style, particularly visual style in Hollywood cinema. Bordwell’s article ‘Intensified Continuity’ in Film Quarterly argues, convincingly, that there have been four major, interlocking changes in the visual style of contemporary American film as compared with what we might call ‘the classic era’: ‘More rapid editing’, ‘Bipolar extremes of lens lengths’, ‘More close framing in dialogue scenes’, and ‘A free-ranging camera’. I wondered if I might find similar changes at work if I compared old and new episodes of soap opera (and I decided to focus my attention on the first and third of the features Bordwell mentions).

My investigation took the form of close analysis of two pairs of five episode ‘snapshots’ of Coronation Street: episodes 3 to 7, from December 1960, and episodes 8174 to 8178, from July 2013. (This ‘snapshot’ method has precedents in the work of Christine Geraghty and Jeremy Butler.) I recorded the number of scenes and their durations for each of the ten episodes I analysed. I then took one episode from each of the five samples and went down to the more fine-grained level of counting shots. The other thing I was thinking about during my analysis, in an inevitably slightly less systematic way, was the differences in the ways my two samples represented ‘the everyday’. Let’s take each of these three parts of my analysis in turn.

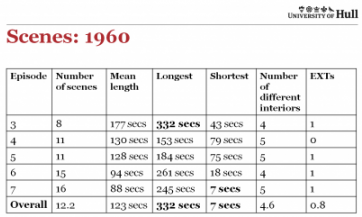

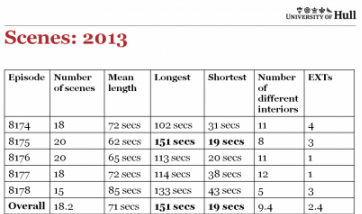

Noting scene durations and locations for each of my ten case study episodes allowed me to establish for each episode the number of scenes, average scene length, the lengths of the longest and the shortest scenes, the number of different locations used in each episode, and the number of exteriors. So here, briefly, are the stats for the first five episodes and the stats for five recent episodes:

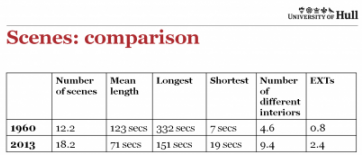

These statistics become more interesting and revealing when you average them out for each of the two five episode snapshots and compare them:

We can see that compared with the 2013 episodes, the very early episodes of Coronation Street had fewer scenes across fewer different locations. Logically, fewer scenes means that each one is longer, almost twice as long on average as a contemporary scene. Note also, though, how the range of different scene lengths in the early episodes is so much greater. The longest scene in the early episodes is more than twice as long as the longest in the contemporary ones. Perhaps slightly more surprisingly, the shortest scene in the early episodes is nearly three times as short as that in the contemporary ones.

What we can see here is the two moments of Coronation Street exhibiting two different kinds of variety. In the contemporary episodes, a main source of variety is to move quickly between a large number of different locations (though not actually that many more storylines). In the early episodes, variety is provided instead by scenes of differing lengths. I’ll have more to say about these macro-level statistics later, but for now let’s turn our attention to something a bit more fine-grained.

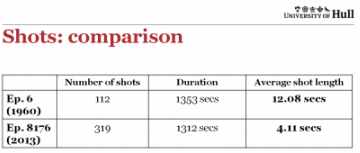

From within my five episode samples, I chose one episode, and counted the number of shots in each scene.

As we will recall, in ‘Intensified Continuity’, Bordwell links the dropping average shot length of Hollywood movies to a range of other ‘stylistic tactics’, including ‘more close framings in dialogue scenes’. And although one does find close-ups in the early episodes and some limited staging in depth in the contemporary episodes, overall, it seems fair to say that contemporary Coronation Street is heavily built around shot-reverse shot medium close-ups, whereas the early episodes often favour frontal long two shots as a default staging schema. In fact, even when the staging set-up means that a long take would be possible as long as the actors were careful with their heads, contemporary Coronation Street still opts for analytical editing. It makes sense that shorter shots and closer framings go together as a rule, because if the viewer has less time to decide what to look at, the thing that they need to see had better be right there in front of them. However, we ought to remember that although the more flexible editing procedures of contemporary soap opera compared with early soap opera filming facilitate lots of cutting, the shooting procedures in no way necessitate it. It seems rather to be a way of doing things that stems from a perceived need, in a highly competitive television environment, to keep things moving.

As we will recall, in ‘Intensified Continuity’, Bordwell links the dropping average shot length of Hollywood movies to a range of other ‘stylistic tactics’, including ‘more close framings in dialogue scenes’. And although one does find close-ups in the early episodes and some limited staging in depth in the contemporary episodes, overall, it seems fair to say that contemporary Coronation Street is heavily built around shot-reverse shot medium close-ups, whereas the early episodes often favour frontal long two shots as a default staging schema. In fact, even when the staging set-up means that a long take would be possible as long as the actors were careful with their heads, contemporary Coronation Street still opts for analytical editing. It makes sense that shorter shots and closer framings go together as a rule, because if the viewer has less time to decide what to look at, the thing that they need to see had better be right there in front of them. However, we ought to remember that although the more flexible editing procedures of contemporary soap opera compared with early soap opera filming facilitate lots of cutting, the shooting procedures in no way necessitate it. It seems rather to be a way of doing things that stems from a perceived need, in a highly competitive television environment, to keep things moving.

The persistent pursuit of rapid editing and close framings has its costs, as Bordwell notes in relation to Hollywood cinema:

In intensified continuity, the face is privileged, especially the mouth and eyes. […] Eyes have always been central to Hollywood cinema, but usually they were accompanied by cues emanating from the body. Performers could express emotion through posture, stance, carriage, placement of arms, and even the angling of the feet. Actors knew how to rise from chairs without using hands to leverage themselves, to pour drinks steadily for many seconds, to give away nervousness by letting a fingertip twitch. Physiques […] are more frankly exposed than ever before, but they seldom acquire grace or emotional significance.1

Returning to Coronation Street, and turning to the issue of the representation of the everyday, I would note that the default framing choices of the show in its contemporary form, along with the accelerated dramatic pace that accompanies them, work together to largely preclude the representation of leisure and other everyday activities. A scene in contemporary Coronation Street will often begin with a bit of ‘business’. For example, the scene between Eileen and Paul begins with him polishing his shoes. However, once the dramatic business of the scene gets underway, which usually happens very quickly, we move in to medium close-ups, and aside from taking sips of a drink or bites of a biscuit, or wiping down a table or passing a plate over a counter, the characters will tend to cease other activities and just talk. Something that is very common in early Coronation Street is for scenes to have developed beginnings, middles and endings. One effect of the greater number of scenes in contemporary Coronation Street is that by comparison they feel truncated. There may be, as already mentioned, a token initial phase, but very soon the characters and their dialogue focus entirely upon dramatic problems, and there are rarely the grace notes at the end of scenes that were one of the great pleasures of early Coronation Street.

Returning to Coronation Street, and turning to the issue of the representation of the everyday, I would note that the default framing choices of the show in its contemporary form, along with the accelerated dramatic pace that accompanies them, work together to largely preclude the representation of leisure and other everyday activities. A scene in contemporary Coronation Street will often begin with a bit of ‘business’. For example, the scene between Eileen and Paul begins with him polishing his shoes. However, once the dramatic business of the scene gets underway, which usually happens very quickly, we move in to medium close-ups, and aside from taking sips of a drink or bites of a biscuit, or wiping down a table or passing a plate over a counter, the characters will tend to cease other activities and just talk. Something that is very common in early Coronation Street is for scenes to have developed beginnings, middles and endings. One effect of the greater number of scenes in contemporary Coronation Street is that by comparison they feel truncated. There may be, as already mentioned, a token initial phase, but very soon the characters and their dialogue focus entirely upon dramatic problems, and there are rarely the grace notes at the end of scenes that were one of the great pleasures of early Coronation Street.

A good example of the earlier approach to scene construction is the first scene of the sixth episode. It begins with Christine Hardiman sitting down and doing a bit of sewing. Then her mother, May, comes home along with Esther and Lucille. There is an argument about the garment, ending with Christine throwing it in the fire and storming out. Esther tells May that she will arrange to borrow Ida Barlow’s stole for Christine’s date. Esther leaves Lucille with May.

A good example of the earlier approach to scene construction is the first scene of the sixth episode. It begins with Christine Hardiman sitting down and doing a bit of sewing. Then her mother, May, comes home along with Esther and Lucille. There is an argument about the garment, ending with Christine throwing it in the fire and storming out. Esther tells May that she will arrange to borrow Ida Barlow’s stole for Christine’s date. Esther leaves Lucille with May.

From behind, we see May stagger, then the screen goes blurry as she is afflicted by head pain. She asks Lucille to stop her pacing. Lucille kicks off her borrowed heels and sits down, peeved; the scene ends. Within this rise and fall of dramatic action we get much more than the stand-and-deliver, or sit-and-deliver, dialogue that typifies the contemporary programme. Many scenes in early Coronation Street will begin with characters alone and doing something for a good few moments until someone enters the room or knocks on the door. Later in the episode we will see May, in the same location, play on the piano for a good while before Esther knocks. Often, a prop will be carried through a fair duration of the scene too, giving the actor a prop to engage with and adding texture and rootedness to the scene.

From behind, we see May stagger, then the screen goes blurry as she is afflicted by head pain. She asks Lucille to stop her pacing. Lucille kicks off her borrowed heels and sits down, peeved; the scene ends. Within this rise and fall of dramatic action we get much more than the stand-and-deliver, or sit-and-deliver, dialogue that typifies the contemporary programme. Many scenes in early Coronation Street will begin with characters alone and doing something for a good few moments until someone enters the room or knocks on the door. Later in the episode we will see May, in the same location, play on the piano for a good while before Esther knocks. Often, a prop will be carried through a fair duration of the scene too, giving the actor a prop to engage with and adding texture and rootedness to the scene.

In addition to the counting and timing parts of my analysis, I also performed a somewhat Roland Barthes-like analysis upon one episode from each of the sets of five: I came up with a set of ‘codes’ used to categorise the action and/or emotional tenor of each scene. The purpose of this was to try to substantiate and further flesh out my sense that early Coronation Street not only finds more time, and space, for the representation of moments of leisure, pause, and domestic labour, but also that it possesses not only a slower dramatic pace, but a lower dramatic pitch. It is probably something of a critical commonplace that soap operas nowadays have more conflict and antagonism on display than they used to, but I still found it revealing to use tools of close analysis to develop this intuition. So here are my unscientific but detailed ‘tags’, to use a contemporary term, for the two episodes in turn.

In addition to the counting and timing parts of my analysis, I also performed a somewhat Roland Barthes-like analysis upon one episode from each of the sets of five: I came up with a set of ‘codes’ used to categorise the action and/or emotional tenor of each scene. The purpose of this was to try to substantiate and further flesh out my sense that early Coronation Street not only finds more time, and space, for the representation of moments of leisure, pause, and domestic labour, but also that it possesses not only a slower dramatic pace, but a lower dramatic pitch. It is probably something of a critical commonplace that soap operas nowadays have more conflict and antagonism on display than they used to, but I still found it revealing to use tools of close analysis to develop this intuition. So here are my unscientific but detailed ‘tags’, to use a contemporary term, for the two episodes in turn.

Coronation Street, Episode 6 (28 December 1960)

Scene ‘Actions’/[Staging/mise-en-scène] ‘Codes’

Scene ‘Actions’/[Staging/mise-en-scène] ‘Codes’

1 (Hardimans’) Christine and May argue over a garment; May suffers with head pain. Sewing, sitting, throwing a garment in the fire [‘subjective’ shot], family, conflict, fashion, neighbourly support, borrowing, dressing-up.

2 (Elsie’s) Dennis’s recent trouble with the police is discussed. Pouring tea, reading, family, conflict, concealment, persecution, chat, leisure, work.

3 (Hardimans’) May leaves Lucille alone in the house; once the coast is clear, Lucille goes for Christine’s dress. Putting on a coat and hat, reading on the floor, looking in the mirror, family, reading, chat, fashion, domesticity, childhood, school.

4 (Hospital) Ena accuses Esther of trying to steal her job. [Staging around a bed.] Family, conflict, illness, misanthropy.

5 (Rovers) Ron Bailey holds forth about the life of an insurance salesman. [Staging around a bar, single shot.] Male camaraderie, tale-telling, drinking, chat.

6 (Elsie’s) Elsie is disturbed from her ironing by carol singers. Ironing, fixing a lamp. [Single shot.] Chores, interruption, domesticity.

6 (Elsie’s) Elsie is disturbed from her ironing by carol singers. Ironing, fixing a lamp. [Single shot.] Chores, interruption, domesticity.

7 (Outside Elsie’s) She chastises them but gives them some coins anyway. [Single shot.] Children, Christmas, community, singing.

8 (Elsie’s) Elsie worries about Dennis. [Single shot.] Family, chores, domesticity, worry.

9 (Hardimans’) Lucille twirls in Christine’s frock; Christine returns, berates Lucille, then bursts into tears when she sees dirt on the hem. Sustained silent twirling, childhood, fashion, mischief, dressing-up, conflict.

End of part one

10 (Hardimans’) The dress has been cleaned and all is well. May, Esther and Lucille see Christine off when she is called on by Malcolm. Piano playing, reconciliation, courtship, dressing-up, music, interruption.

10 (Hardimans’) The dress has been cleaned and all is well. May, Esther and Lucille see Christine off when she is called on by Malcolm. Piano playing, reconciliation, courtship, dressing-up, music, interruption.

11 (Elsie’s) Dennis reveals that the police suspect him of a robbery and he has no alibi. [Staging around a table.] Conflict, persecution, crime, family, waiting, worry.

12 (Rovers) Esther gossips about Ena. Harry talks to Elsie and it turns out that he saw Dennis at the time of the robbery (elsewhere) so can act as his alibi. [Staging around a table.] Gossip, resolution, support, crime, humour.

13 (Elsie’s) Ivan returns just in time to deliver the good news to Dennis and thus prevent him from eloping. [Single shot.] Resolution, support, family, persecution.

13 (Elsie’s) Ivan returns just in time to deliver the good news to Dennis and thus prevent him from eloping. [Single shot.] Resolution, support, family, persecution.

14 (Hospital) A nurse finds Ena’s bed empty. [Single shot.] Illness, humour.

15 (Outside hall) Christine and Malcolm kiss and talk over their evening. Ena steps out of a taxi, berates the driver, and goes into the community hall. Courtship, romance, humour, misanthropy.

Conflict: 5 (33%)

Misanthropy: 2 (13% – and one character!)

Persecution: 3 (20%)

Concealment: 1 (7%)

Humour: 3 (20%)

Coronation Street, Episode 8176 (24 July 2013)

Scene ‘Actions’/[Staging/mise-en-scène] ‘Codes’

Scene ‘Actions’/[Staging/mise-en-scène] ‘Codes’

1 (Croppers’) Hayley escorts a sleep-walking (sleep-cleaning) Roy back to bed. Cleaning a table. [Single shot.] Illness, caring for a loved one, relationships, support.

2 (Eileen’s) Eileen and Paul talk over his disciplinary hearing. Polishing shoes, putting shoes on. [Shot-reverse shot (SRS), MCUs.] Work-related problems, persecution (perceived), relationships, conflict, support, advice.

3 (Croppers’) Sylvia adopts some of Hayley’s chores; Roy researches cancer on his laptop. Laptop, dusting, putting kettle on. [Staging in depth.] Illness, caring for a loved one, relationships, support, family.

4 (EXT) Carla, trying to motivate Peter, offers him work at the factory; Paul emerges from Eileen’s house and there is a cross-street slanging match about his racist comment in the pub. [Walk-and-talk staging followed by MCU SRS.] Conflict, despondency, relationships, racism.

5 (Croppers’) Roy tries to persuade Hayley to eat healthily and to rest. Eating (minimal). [Staging around a table.] Conflict, illness, caring for a loved one, relationships, support, health, advice, support, family.

6 (Shop) Jason helps Tracy and Rob convert Peter’s bookmakers into a pawn shop. ‘Measuring up’, petting. [MCU SRS.] Enterprise, conflict, misanthropy.

7 (Factory floor) Hayley persuades Carla to let her work and not let the other worker’s know about Hayley’s diagnosis. Walking across a room, standing with a drink and a biscuit. [SRS.] Employer-employee relationships, female camaraderie, concealment, humour, solicitude, work, support.

8 (Bar) Leanne tries to help Nick figure out who has it in for him. Getting off the phone, standing behind the bar. [MCU SRS.] Persecution, relationships, advice, support, work-related problems, work.

9 (Deirdre’s) Carla visits Deirdre for advice about how to get through to Peter. Visiting, sipping drinks. [Staging around a table, MCU SRS.] Family, despondency, advice, support.

End of part one

10 (Cafe) Frayed tempers in the cafe lead to Roy and Anna storming out on separate family matters. Serving food, being served, laptop. [Staging around a counter.] Employer-employee relationships, work, family, illness, family breakdown, conflict, concealment.

11 (Shop) Peter argues with Rob about the value of some assets; Tracy tries to mediate. Disturbed by a phone call, standing and arguing. [MCU SRS.] Conflict, family, attempted mollification, enterprise, money, misanthropy.

12 (Cafe) Hayley arrives to collect Roy but he is still out. Wiping menus, family, relationships, illness, work, support.

13 (Anna’s) Tim tells Faye (his daughter) that he is leaving in search of work. [Sitting on a sofa and chair; MCU SRS.] Family, family breakdown, abandonment, fatherhood, conflict.

14 (Bar) Carla has two proposals for Peter, Nick laments his misfortune. Eating a pasty. [Staging around a table, and a bar.] Conflict, concealment, persecution, deception, relationships, romance, support.

15 (Rovers) Paul and Eileen’s drink is disturbed when Sally verbally attacks Paul for his earlier behaviour; Eileen and Sally have to be restrained from hitting one another. Near-physical violence, conflict, physical aggression, relationships, support, racism.

16 (Bar) Carla asks Peter to become her business partner and her husband. [Staging around a table, MCU SRS.] Relationships, proposal, support, marriage, romance, enterprise.

17 (Rovers) Tim shares his problems with Sally; she encourages him not to move away. [MCU SRS] Solicitude, support, advice, friendship, romance.

18 (Hospital) Hayley arrives at hospital; Roy too, just in time. [Walk-and-talk.] Relationships, support, health.

19 (Bar) Carla and Peter continue to talk; Nick et al look on and make off-colour remarks. Relationships, proposal, support, marriage, enterprise, romance, misanthropy.

20 (Hospital) Roy and Hayley express different perspectives on Hayley’s illness. [Sitting next to each other.] Relationships, support, health.

Conflict: 8 (40%)

Misanthropy: 3 (15% – and several characters!)

Persecution: 2 (10%)

Concealment: 3 (15%)

Humour: 1 (5%)

It would be too laborious to try to address everything that these tables highlight, which is why I’ve drawn out some key tags and their frequency at the bottom. It is worth saying that although the statistics for conflict and misanthropy are not as different as I thought they would be, we need also to distinguish between the severity and distribution of these things, which the tagging system cannot do. Some of the conflict in the 1960 episode revolves around Lucille messing around in Christine’s frock, and it’s resolved by the end of the episode. By contrast, in the 2013 episode, the conflict is generally much more acrimonious. Indeed, conflict and misanthropy are generally much closer to the surface, and spread across many more characters, and it apparently takes very little to draw these things out. Tracy and Rob are, of course, villains, and constantly needle everyone they encounter. However, in the cafe, Roy, Anna and Sylvia very quickly start squabbling. Sally uses Paul’s laughter as a pretext for attacking him in the pub, and is soon offered a ‘bed in A and E’ by Eileen for her trouble. Although Nick and Leanne and Peter and Carla have a history, it seems simply mean-spirited for Leanne to say ‘Looks like the alkies are getting spliced’ and for Nick to add ‘At least they’ll be out of our hair.’

This difference in emotional tenor is, I think, heightened by the fact that in contemporary Coronation Street, characters barely pause for breath before talking about their problems and each other – and nothing else. Early Coronation Street made the time and the space to show us its characters reading, sewing, playing the piano, ironing, waiting, pacing, fixing a lamp, twirling, and singing (and all of this in just one episode). Often, characters would do these things alone, at least for a few moments. Of course, everyday life itself has changed significantly for working people in Manchester between 1960 and 2013. However, the thing that I’ve been trying to suggest in my analysis is that Coronation Street’s ways and means of representing that everyday have also changed. More specifically, they have narrowed quite substantially, and I take this to constitute a loss that is both aesthetic and social.

This difference in emotional tenor is, I think, heightened by the fact that in contemporary Coronation Street, characters barely pause for breath before talking about their problems and each other – and nothing else. Early Coronation Street made the time and the space to show us its characters reading, sewing, playing the piano, ironing, waiting, pacing, fixing a lamp, twirling, and singing (and all of this in just one episode). Often, characters would do these things alone, at least for a few moments. Of course, everyday life itself has changed significantly for working people in Manchester between 1960 and 2013. However, the thing that I’ve been trying to suggest in my analysis is that Coronation Street’s ways and means of representing that everyday have also changed. More specifically, they have narrowed quite substantially, and I take this to constitute a loss that is both aesthetic and social.

James Zborowski is Lecturer in Film and Television Studies at the University of Hull. He has recently returned to Coronation Street in order to investigate performance in contemporary British soap opera.

This was originally a paper delivered at the Spaces of Television conference at the University of Reading on 19 September 2013. It is presented here with minor revisions.

Originally posted: 1 March 2016.

James has subsequently returned to this topic with new statistics involving episodes from 2016: see ‘Soap Stats’ at Between Sympathy and Detachment (6 December 2016).

Pingback: Soap stats | Between Sympathy and Detachment