by DAVID ROLINSON

Half Hour Story Writer: Alun Owen; Producer: Stella Richman; Director: Alan Clarke

The BFI’s superb new Alan Clarke box sets contain many treats – they at last make most of the director’s surviving BBC work available to everyone and do so with such loving remastering and restoration that even those of us who have seen these pieces many times have never seen or heard them like this – but I’m particularly pleased with the bonus DVD on the main blu ray set Dissent and Disruption: The Complete Alan Clarke at the BBC.1 This collects several of Clarke’s early plays for the ITV strand Half Hour Story (1967-68), including pieces that were thought lost from the archive.2 I say more about Half Hour Story in my new essays for the blu ray booklet, and more about this and Clarke’s other early ITV work in my book Alan Clarke (2005);3 however, this website essay revisits Stella (1968), one of my favourite Half Hour Story plays, to study it in more detail.4 Clarke is rightly being celebrated by film critics for his filmed drama, but we should not forget that he was also a master of the electronic multi-camera studio. This results in such impressive studio experiments as Danton’s Death (1978), Psy-Warriors (1981) and Baal (1982), but there are signs of his qualities in Stella and the other plays that he made at Wembley Studios in his early days at Rediffusion.

The BFI’s superb new Alan Clarke box sets contain many treats – they at last make most of the director’s surviving BBC work available to everyone and do so with such loving remastering and restoration that even those of us who have seen these pieces many times have never seen or heard them like this – but I’m particularly pleased with the bonus DVD on the main blu ray set Dissent and Disruption: The Complete Alan Clarke at the BBC.1 This collects several of Clarke’s early plays for the ITV strand Half Hour Story (1967-68), including pieces that were thought lost from the archive.2 I say more about Half Hour Story in my new essays for the blu ray booklet, and more about this and Clarke’s other early ITV work in my book Alan Clarke (2005);3 however, this website essay revisits Stella (1968), one of my favourite Half Hour Story plays, to study it in more detail.4 Clarke is rightly being celebrated by film critics for his filmed drama, but we should not forget that he was also a master of the electronic multi-camera studio. This results in such impressive studio experiments as Danton’s Death (1978), Psy-Warriors (1981) and Baal (1982), but there are signs of his qualities in Stella and the other plays that he made at Wembley Studios in his early days at Rediffusion.

The play opens with Stella (Geraldine Moffatt) alone in her new bedsit, just before her boyfriend for the last two years, credited only as The Man (Ray Smith), arrives in order to try to reclaim her. After a seven day separation, she tells him that ‘our time is over… I’ve moved on’. She has had time to think, to examine what binds people together, and the results are both disturbing and witty. For example, Stella admonishes her former boyfriend for consulting the ‘Sigmund Freud bumper Christmas annual’, which is a potentially self-aware touch from writer Alun Owen, given that one reviewer had described his dialogue in Shelter (an earlier collaboration with Clarke) as risking ‘self-taught Freudian psychology’.5 Stella’s point of view is central to this play; she is aware that there has been ‘a tendency for communications to break down between us, unless I abandon my own point of view and suffer yours’. Stella’s subjectivity is central to the dialogue – in particular through her resistance of gender stereotyping and, as we have seen, psychoanalysis – but it is also central to the style as Clarke’s distinctive approach heightens the play’s themes.

Reviewers prioritised writer Alun Owen. That is not surprising – Owen was a highly acclaimed writer and the discourses surrounding television authorship have mostly privileged the writer, which set me a challenge when writing a book about Clarke as a television director – but some reviewers were keen to directly compare the contributions of Stella’s writer and director. In the Financial Times, T. C. Worsley admired this ‘masterly piece of writing,’ but tried to imagine Clarke’s response as director:

Reviewers prioritised writer Alun Owen. That is not surprising – Owen was a highly acclaimed writer and the discourses surrounding television authorship have mostly privileged the writer, which set me a challenge when writing a book about Clarke as a television director – but some reviewers were keen to directly compare the contributions of Stella’s writer and director. In the Financial Times, T. C. Worsley admired this ‘masterly piece of writing,’ but tried to imagine Clarke’s response as director:

[…] since [Stella] consisted exclusively of this duologue, unravelling the past and shattering the present, it didn’t make what they call ‘good television’. What is the director to do with nothing but this uninterrupted flow of talk? How can he keep up the visual interest? How help to make the crucial points and underline the climaxes?6

The answer was a set of techniques which support Moffatt’s compelling central performance: not only unflinching close-ups which hold on her as she makes her case but also inventive studio camerawork and blocking. Before I go into more detail, it is worth noting that not everyone would agree with my verdict. Worsley argued that that ‘Alan Clarke, understandably baffled by the problem, resorted to some rather gimmicky camera work’, which Worsley thought was ‘distracting rather than illuminating’. As far as Worsley was concerned, Clarke should have ‘kept very quiet, frankly admitting the impossibility of the task set him’.7 (This comment would seem dismissive – Clarke hardly ‘kept very quiet’ with his style in his 1980s filmed dramas or his experiments with the language of multi-camera video drama – were it not for the fact that some of his devastatingly beautiful 1970s dramas, such as Diane (1975), made such a virtue of sitting back in sympathetic, elegantly-composed observation.) Similarly, in The Times, Michael Billington found Clarke’s direction of Stella ‘rather mannered and self-advertising’.8

In order to develop my argument – or, if you do not agree with my admiration for Stella, to provide evidence to support the critics’ objections – this essay will explore the play’s first few shots, while putting them in the vital context of the circumstances in which Clarke was working. According to the production paperwork, Stella was recorded in Studio 5B at Wembley Studios on 19 January 1968. The schedule for the studio day was, with minor variations, typical for Half Hour Story. After setting and lighting between 9:30 and 11:00, there was a camera rehearsal between 11:00 and 1:00 (as was standard practice, the production had several days of rehearsal away from the studio but now the director and actors got to work on the sets, and run through for camera and sound issues as the director’s camera script was put through its paces). After a ‘lunch break’ (1:30-2:30) there were further camera rehearsals between 2:30 and 6:00, a ‘dinner break’ (6:00-7:00) and a final camera rehearsal between 7:00 and 8:00. Make-up and line-up took place between 8:00 and 9:00, after which the 25-minute play was recorded between 9:00 and 10:00, after which the sets needed striking (taking down) for the next day.

Clarke’s camera scripts were often ambitious, posing challenges for everyone but in particular for the camera crews (different crews were assigned for different plays: Trevor Saunders and Crew 6 were assigned to Stella) and vision mixers (Daphne Renny). (As a general rule of thumb: in multi-camera studio drama, cutting between shots means the careful timing of cuts or mixes between the outputs of different cameras following the action simultaneously rather than being composed and lit individually, except in use, where possible, of telecine – inserts shot on film prior to the studio day – or drop-in shots taken at the end of studio sessions.) In Alan Clarke I used the studio schedule for Clarke’s To Encourage the Others (1972) as a starting point to explore debates among programme makers on the perceived merits or otherwise of making dramas in the studio. This current essay is more concerned with Clarke’s use of these methods.

The camera script for Stella opens with a fade-in to a close-up of an ashtray, followed by a slow pan up to a low-angle medium-close-up of Stella.9 The completed programme instead starts with a straight cut to the shot of Stella. There are often differences between Clarke’s camera scripts and the completed programmes, which usually serve to simplify the shooting (see my pieces on Shelter and The Gentleman Caller in the blu ray booklet for details of quite big changes to the handling of key scenes in those plays), which is one reason why it’s difficult to write about programmes that no longer survive in the archives. However, at the start of Stella, there are extra shots which make things a little more complicated.

Occupying two thirds of the shot, left and centre of frame, Stella gazes thoughtfully off-camera (slightly to screen right) and takes two drags on her cigarette. Camera 3 continues to hold on Stella, not tempted to follow the movement of her hand (in camera-script speak, ‘let hand go O.O.S. hold MCU’),10 and with no reverse-field cut to what she is looking at, even when she momentarily gazes nervously further right. After all, there is nothing there – at first. A noise motivates her to turn her head and, now in profile, she looks off-screen right. (Noise brings to mind sound, which I’m neglecting a little here. Camera scripts include not only camera instructions but also sound details, including the playing-in of music or effects on ‘grams’ and the provision of microphones. Camera scripts detail not only which camera takes each shot but also which position they are in – so that, say, Camera 1 knows where it has to be in each scene, when it needs to move to a different part of a set while a scene is still continuing or to a different set elsewhere in a studio, all without ending up in shot or ‘knitting’ [tangling] cables with other cameras – and something similar applies to sound (overseen on Stella by Cyril Vine). Therefore, these first few shots alternated between Boom A and a mini-boom and elsewhere in the play there is the use of Boom B, a fishpole in the bedroom and, at the start of Part 2, a concealed microphone in a flowerbox.)

Occupying two thirds of the shot, left and centre of frame, Stella gazes thoughtfully off-camera (slightly to screen right) and takes two drags on her cigarette. Camera 3 continues to hold on Stella, not tempted to follow the movement of her hand (in camera-script speak, ‘let hand go O.O.S. hold MCU’),10 and with no reverse-field cut to what she is looking at, even when she momentarily gazes nervously further right. After all, there is nothing there – at first. A noise motivates her to turn her head and, now in profile, she looks off-screen right. (Noise brings to mind sound, which I’m neglecting a little here. Camera scripts include not only camera instructions but also sound details, including the playing-in of music or effects on ‘grams’ and the provision of microphones. Camera scripts detail not only which camera takes each shot but also which position they are in – so that, say, Camera 1 knows where it has to be in each scene, when it needs to move to a different part of a set while a scene is still continuing or to a different set elsewhere in a studio, all without ending up in shot or ‘knitting’ [tangling] cables with other cameras – and something similar applies to sound (overseen on Stella by Cyril Vine). Therefore, these first few shots alternated between Boom A and a mini-boom and elsewhere in the play there is the use of Boom B, a fishpole in the bedroom and, at the start of Part 2, a concealed microphone in a flowerbox.)

There is now a cut to the source of the noise: The Man arrives. Again there is a change from the camera script: there, this shot begins with a doorknob from which there is a crab [sideways movement of pedestal camera] and a pan up to a low-angle medium-shot of The Man. (To follow my earlier point, Camera 4 here crabs from Position A to Position B in this introduction to The Man.) Other Clarke pieces of the period dwell on domestic objects – Goodnight Albert in particular – but this symbolic play on corresponding props (ashtray and doorknob) gives way to a more compelling pairing of introductory shots which heighten the clash between the characters. As The Man enters room 46C the two make contact – shot in profile, looking left, he matches Stella’s profile shot looking right – but it is disorienting in terms of different angles and shot sizes. The low-angle shot displays the ceiling – which Clarke’s studio plays often do, though there are other directors at ITV in the period who do comparable things, in particular Bill Bain and Jim Goddard – and, although the camera moves to accommodate his movement, he blocks most of the frame.

There is now a cut to the source of the noise: The Man arrives. Again there is a change from the camera script: there, this shot begins with a doorknob from which there is a crab [sideways movement of pedestal camera] and a pan up to a low-angle medium-shot of The Man. (To follow my earlier point, Camera 4 here crabs from Position A to Position B in this introduction to The Man.) Other Clarke pieces of the period dwell on domestic objects – Goodnight Albert in particular – but this symbolic play on corresponding props (ashtray and doorknob) gives way to a more compelling pairing of introductory shots which heighten the clash between the characters. As The Man enters room 46C the two make contact – shot in profile, looking left, he matches Stella’s profile shot looking right – but it is disorienting in terms of different angles and shot sizes. The low-angle shot displays the ceiling – which Clarke’s studio plays often do, though there are other directors at ITV in the period who do comparable things, in particular Bill Bain and Jim Goddard – and, although the camera moves to accommodate his movement, he blocks most of the frame.

This is the sort of shot that critics such as Worsley and Billington singled out for criticism: Clarke’s taste for low-angle shots up Smith’s nostrils (as they put it). However, such stifling nasal close-ups heighten the claustrophobia and, as they recur later, enhance the play’s exploration of human intimacy and its tensions. The Man tries to reclaim Stella – ‘you belong to me’ – and at the end of Part 1 he will trap her against a wall, at which point the framing reminds us of this initial claustrophobia. In that later scene he says that ‘I attack you, I smother you’, and the camera does something similar, as is hinted at by this introduction.

This is the sort of shot that critics such as Worsley and Billington singled out for criticism: Clarke’s taste for low-angle shots up Smith’s nostrils (as they put it). However, such stifling nasal close-ups heighten the claustrophobia and, as they recur later, enhance the play’s exploration of human intimacy and its tensions. The Man tries to reclaim Stella – ‘you belong to me’ – and at the end of Part 1 he will trap her against a wall, at which point the framing reminds us of this initial claustrophobia. In that later scene he says that ‘I attack you, I smother you’, and the camera does something similar, as is hinted at by this introduction.

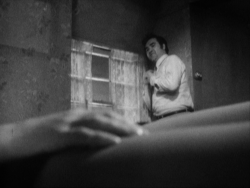

The next few shots largely follow the camera script, barring a slight alteration to their running order. We return to Stella still in profile looking right, stressing her reaction. Next there is the play’s first two-shot, but instead of bringing them together unproblematically in the same frame, the shot provides another moment of visual disorientation which underlines the tensions between them. Camera 2 is again taken from a low angle, but this time marked by a shift in focal length providing a different angle of view,11 achieving depth. Stella is framed in the extreme foreground left of frame, while The Man stands in the background, slightly to the right, his sense of ownership marked in the physicality of his stance as he holds the door and gazes at her legs as she sits in her underwear.

The next few shots largely follow the camera script, barring a slight alteration to their running order. We return to Stella still in profile looking right, stressing her reaction. Next there is the play’s first two-shot, but instead of bringing them together unproblematically in the same frame, the shot provides another moment of visual disorientation which underlines the tensions between them. Camera 2 is again taken from a low angle, but this time marked by a shift in focal length providing a different angle of view,11 achieving depth. Stella is framed in the extreme foreground left of frame, while The Man stands in the background, slightly to the right, his sense of ownership marked in the physicality of his stance as he holds the door and gazes at her legs as she sits in her underwear.

Similar shots occur later, with Stella appearing as almost disembodied legs subject to The Man’s gaze as he sits in the background as if on the naughty step. If the central relationship echoes the films of Antonioni then Moffatt is, as Richard Kelly observed in BFI screening notes in 2002, ‘lovingly framed by Clarke as though she were Monica Vitti’.12 Clarke uses two-shots to express distance, repeatedly foregrounding Stella screen left looking right, with the man in the background, centre of frame. Fittingly since we are disoriented by the fluctuation of power and accusation between them, our views of both are fragmented. In profile, as in this shot, she appears as a disembodied leg subjected to our gaze as much as his, whilst our view of him shifts uncomfortably in regular changes in shot size, angle and framing. This is just one of the ways in which Clarke’s visual strategies emphasise the play’s themes of distance and intimacy and the construction of gender roles. There are other ways in which these themes are addressed: for example, later, during a conversation about putting ‘space between us’ – though not directly cued by that phrase – the camera pulls focus.13

Returning to the opening sequence, after the two-shot mentioned above there is another exchange of looks – Stella in profile, The Man from a low angle as he closes the door and smiles at her, then Stella in profile again. As she begins to stand there is a cut on action, back to Camera 2, her legs moving as he gazes; however, the camera now crabs left quickly (to Position B) until she exits the room.

There is now a cut to Camera 1,14 at a low angle foregrounding the bed rail. (During this shot, Camera 2 moved to Position 3A and Camera 3 to Position B.) There are lingering memories of the British New Wave and its antecedents – bed rails and other foregrounded domestic spaces imprisoning female protagonists in prison or the home in J. Lee Thompson’s Yield to the Night (1956) and Woman in a Dressing Gown (1957), though the latter hardly describes Stella’s initial attire.

There is now a cut to Camera 1,14 at a low angle foregrounding the bed rail. (During this shot, Camera 2 moved to Position 3A and Camera 3 to Position B.) There are lingering memories of the British New Wave and its antecedents – bed rails and other foregrounded domestic spaces imprisoning female protagonists in prison or the home in J. Lee Thompson’s Yield to the Night (1956) and Woman in a Dressing Gown (1957), though the latter hardly describes Stella’s initial attire.

The camera crabs left along the bed before settling at a low angle to watch Stella dress. There are several moments in Clarke’s early Rediffusion plays in which the camera is implicated as men gaze at women – see my booklet essay on The Fifty-Seventh Saturday for instance – but it’s particularly striking here. The camera lingers on this a little too long, but does so from a perspective that so far in the play has been entirely associated with The Man: low-angle, ceiling in shot – as if we are temporarily sharing his gaze or she is in danger of being confined.

The camera crabs left along the bed before settling at a low angle to watch Stella dress. There are several moments in Clarke’s early Rediffusion plays in which the camera is implicated as men gaze at women – see my booklet essay on The Fifty-Seventh Saturday for instance – but it’s particularly striking here. The camera lingers on this a little too long, but does so from a perspective that so far in the play has been entirely associated with The Man: low-angle, ceiling in shot – as if we are temporarily sharing his gaze or she is in danger of being confined.

The next shot underlines that point: back in the living room, she is again confined by foregrounded bars (a shot not in the camera script, though a shot of Stella with foregrounded banisters is stipulated later). The next shot (Camera 2 at Position 3A) follows her feet left, moves to find and foreground her ashtray (on the top of a record player) and moves up to Stella in the movement that replicates the movement originally planned for the play’s opening shot. Finally, in profile, she speaks – ‘Get out!’ – and a conversation begins, with quick reverse-field cutting between Stella and The Man in which most of the return shots of The Man alternate in shot size (shot of Stella / reverse-shot of The Man in low-angle medium shot/shot of Stella/reverse-shot of The Man in close-up) to disorienting effect. (Not until a climactic sequence in Part 2 will there be a consistent movement between big close-ups.) There are clear signatures in Clarke’s 1960s work – quick cutting between profile close-ups, the use of low angles, foregrounding of characters left of frame in conversation with characters in the background – only a few of which survive into his more widely-known 1970s and 1980s work. His studio plays tend to be neglected by film critics – these plays are more difficult to re-label as ‘films’ than filmed plays – and yet he arguably shows his cinema influences (in particular in European art cinema) more explicitly in this work than in his work on film.

The next shot underlines that point: back in the living room, she is again confined by foregrounded bars (a shot not in the camera script, though a shot of Stella with foregrounded banisters is stipulated later). The next shot (Camera 2 at Position 3A) follows her feet left, moves to find and foreground her ashtray (on the top of a record player) and moves up to Stella in the movement that replicates the movement originally planned for the play’s opening shot. Finally, in profile, she speaks – ‘Get out!’ – and a conversation begins, with quick reverse-field cutting between Stella and The Man in which most of the return shots of The Man alternate in shot size (shot of Stella / reverse-shot of The Man in low-angle medium shot/shot of Stella/reverse-shot of The Man in close-up) to disorienting effect. (Not until a climactic sequence in Part 2 will there be a consistent movement between big close-ups.) There are clear signatures in Clarke’s 1960s work – quick cutting between profile close-ups, the use of low angles, foregrounding of characters left of frame in conversation with characters in the background – only a few of which survive into his more widely-known 1970s and 1980s work. His studio plays tend to be neglected by film critics – these plays are more difficult to re-label as ‘films’ than filmed plays – and yet he arguably shows his cinema influences (in particular in European art cinema) more explicitly in this work than in his work on film.

Are the critics right to describe Clarke’s approach to Stella as ‘self-advertising’? It is certainly showy, but as far as I’m concerned is an early example of his ability to marry form with content. Our understanding of the relationship shifts. Stella seems to be another frustrated housewife, dodging the restrictive marriages of Shelter or George’s Room (in which Moffatt plays a much less articulate character dealing with a male visitor), declaring that ‘you can get someone else to cook your chops’. Gender and power shift with language – she condemns him for ‘pretending to be a man’ and thinks he would like to ‘say you were having a baby and I’ll have to marry you. Well, I’m not playing Sir Jasper to your orphan Annie’ – and this is marked by style. At the play’s half-way stage the two characters go to bed, raising the possibility that we have witnessed a psychosexual game akin to Harold Pinter’s The Lover (1963), but in fact this allows Owen to develop the association between sex and power. The second half begins with another evocative shot – Stella lies blankly on the bed, her face and body foregrounded, while in the background he looks smugly out of the window. Tolling bells add to the ambiguous mood, given their associations with both marriage and death. Reviewer Nancy Banks-Smith unpicked the play’s ‘matador-bull business – the goading, the wounding, the charge, the kill’, and found the dialogue ‘tape-recorder accurate’,15 which anticipates director Joseph Losey’s comment to Michel Ciment that Owen was a ‘self-made writer’ who ‘wrote with a tape-recorder’.16 Similarly, Banks-Smith admired the idea of making a play entirely about a row because ‘Anyone could write it in theory. Everyone could appreciate it from experience’, though overall she found the play ‘inadequate’.17

Are the critics right to describe Clarke’s approach to Stella as ‘self-advertising’? It is certainly showy, but as far as I’m concerned is an early example of his ability to marry form with content. Our understanding of the relationship shifts. Stella seems to be another frustrated housewife, dodging the restrictive marriages of Shelter or George’s Room (in which Moffatt plays a much less articulate character dealing with a male visitor), declaring that ‘you can get someone else to cook your chops’. Gender and power shift with language – she condemns him for ‘pretending to be a man’ and thinks he would like to ‘say you were having a baby and I’ll have to marry you. Well, I’m not playing Sir Jasper to your orphan Annie’ – and this is marked by style. At the play’s half-way stage the two characters go to bed, raising the possibility that we have witnessed a psychosexual game akin to Harold Pinter’s The Lover (1963), but in fact this allows Owen to develop the association between sex and power. The second half begins with another evocative shot – Stella lies blankly on the bed, her face and body foregrounded, while in the background he looks smugly out of the window. Tolling bells add to the ambiguous mood, given their associations with both marriage and death. Reviewer Nancy Banks-Smith unpicked the play’s ‘matador-bull business – the goading, the wounding, the charge, the kill’, and found the dialogue ‘tape-recorder accurate’,15 which anticipates director Joseph Losey’s comment to Michel Ciment that Owen was a ‘self-made writer’ who ‘wrote with a tape-recorder’.16 Similarly, Banks-Smith admired the idea of making a play entirely about a row because ‘Anyone could write it in theory. Everyone could appreciate it from experience’, though overall she found the play ‘inadequate’.17

The character Stella destabilises gendered narratives and so does the style of the play. Stella has a fight on her hands – as Banks-Smith observed, ‘the feminine questions getting the masculine answers’.18 Like so many of Clarke’s protagonists, Stella faces a battle to speak in her own voice (she even sounds like Trevor in Made in Britain as she rails against ‘your sort of honesty’). There is no getting away from the fact that Stella is male-authored, and the tensions that this raises can be traced through other Owen-Clarke collaborations on the BFI set. There is much left to say about Stella and Clarke’s work in general – how wonderful it is that other voices can say it, now that so much of his work is now available.

Vitally, Stella reminds us that Clarke’s work, far from being confined to visceral social realism on themes of masculinity as some discussions of his work have claimed, actually contains a vital strand of female-authored and/or female-centred work.

Thanks to the British Film Institute.

This essay contains some material from my book Alan Clarke (MUP, 2005) and my short essay ‘Stella’ in the blu ray release of Dissent and Disruption: The Complete Alan Clarke at the BBC (BFI, 2016).

Originally posted: 31 May 2016.

Updates:

1 June 2016: restored inadvertently-omitted ‘space between us’ point; added endnote on the play’s broadcast date; made minor amendments to paragraph 2 (moving a few words from the second sentence to the first) and closing paragraph and removed one instance of visible coding.

3 June 2016: restored inadvertently-omitted sound credit; added ‘sharpen’ endnote; two minor alterations (one grammatical, one to clarify the point about re-labelling).

15 June 2016: Added images [withheld until the blu ray set was available]; minor alterations to paragraphing and text to help presentation of images; clarified point about disorientation in shot/reverse.

10 July 2016: updated release information regarding BFI Player in essay and endnote.

Pingback: Experiments in colour and electronic film systems: George’s Room (1967)