by DAVID ROLINSON

Four parts. Writer: Stephen Gallagher; Producer: John Nathan-Turner; Director: Paul Joyce

Warriors’ Gate was a visually inventive, conceptually ambitious and idiosyncratic Doctor Who serial, but also a fraught one for Paul Joyce, its director.1 The disagreements behind the scenes have been well documented, and are often discussed as a marker or consequence of the serial’s ambition.2 I’ve researched this serial in the BBC Written Archives Centre production file on Warriors’ Gate and the archive of writer Stephen Gallagher that is held by Hull History Centre,3 studying everything from multiple script drafts and notes on script meetings through to the specs for the set’s timber framed gimbal mirror and a list of supplementary payments for overtime and wig fittings (at productive moments in these archives it was of course difficult not to declare that “I’m finally getting something done!”4 ). However, this essay is not a blow-by-blow production history but a discussion of Joyce’s direction: partly showing how Joyce’s approach helps to convey the serial’s ideas, but mainly showing how debates about the future of Doctor Who’s production methods and the spaces of television circulated around Warriors’ Gate.

I’m saying “spaces of television” to invoke the recent academic research project Spaces of Television. Its conferences, publications and website remind us that the range of methods we use to discuss programmes must keep in sight the contexts in which those programmes were made. Spaces of Television is particularly concerned with the production spaces of television, how “the material spaces of production (in TV studios and on location) conditioned the aesthetic forms of programmes, and how fictional spaces represented on screen negotiated the opportunities and constraints of studio and exterior space, film and video technologies, and liveness and recording”.5 Spaces of Television has provided an excellent focus for discussion of the spaces in which drama is made, incorporating and foregrounding the testimony of people who make programmes. It adds valuably to the long-term work of several academics, and of Doctor Who fans and independent archive television scholars. These include the peerless, inspirational Andrew Pixley – who has played a leading role in the understanding of Doctor Who’s production history and wider television contexts – and Ian Potter, who provided an exemplary study of the impact of production methods, technologies and institutional practices on the (times and) spaces constructed by Doctor Who in his article on “world-building in Studio D and its legacy”.6 As these and other pieces show, to the production spaces of television we can add the industrial or institutional spaces of television: how programmes take place within an industry whose practices, policies, regulation, schedules and so on help to shape their form, content and of course their very existence. Doctor Who provides many potential insights into spaces of television – from Saturday night-ness to its current place in the strategy of BBC Worldwide/BBC America – but Warriors’ Gate is particularly useful in foregrounding the production spaces in which Doctor Who operated.

Description

It’s a sign of the richness of the serial that this essay will hardly move beyond the first four minutes of episode one…

At the start of episode one we explore the privateer that is captained by Rorvik. We find the Tharils who are chained up as slaves, the less-than-enthusiastic human crew, and the captive Biroc who is being forced to navigate. As a Tharil, Biroc is a “time-sensitive”: he can visualise, and therefore find, a way through the timelines. At the end of the sequence, he visualises the Doctor’s TARDIS.

It’s an unsettling opening, with a restlessness conveyed by camera movement, reframing by zooms, and dissolves. The first shot is a close-up of machinery bathed in cool blue light, before we simultaneously zoom out and pan to discover Tharils, and wonder whether the equipment is life support or a form of confinement – but they’re glowing, indicating their potential power. Notwithstanding the sensible comparison that has been made between the bunk scenes and slave-ship scenes in Roots,7 fans might note that variations on this setting and/or design have appeared in Doctor Who enough times – from the market-stall spider parliament of Planet of the Spiders (1974) to the freeze-packed human buffets of The Ark in Space (1975) and The Horns of Nimon (1980) – for us to realise how differently it’s handled here in composition, design and lighting. As in those stories, our sighting of them works as narrative revelation – we need more information about these imprisoned, possibly tortured alien slaves – but rather than providing functional description the style makes us more aware than usual that we are being shown what we see. The function of the camera and editing is enunciative and authorial, as exploring physical space takes priority over establishing narrative space. (If it is physical space we’re exploring.) The camera tracks backwards, round and back up the corridor, a moving shot from which we dissolve to another moving shot, this time a low-angle shot looking up at a grilled ceiling/walkway. There is another dissolve to movement, this time a pan right to left, showing a wall. There is another dissolve to movement, this time a pan in the opposite direction, left to right, which combines with a zoom-out to two as-yet-unidentified crew members playing cards. This slow movement yields to a dissolve that begins with the two crew members in the same part of the frame as they were at the end of the previous shot, as if smoothing over the transition between two different shots to make the movement feel continuous, as a crane shot takes us up onto the main gantry, where we pan and zoom to see the main crew members and, ultimately, Biroc.

“I was trying to bring film consciousness to bear on TV”

Joyce described the opening of episode one as “an attempt to stamp some directorial authority”, and to provide “tension” that would suck the viewer in. He’s right, but perhaps we could amend “tension” to “a tension”, because it doesn’t just create atmosphere but also sets up a dialogue between the style and content or even between this serial’s style and how Doctor Who usually works. Indeed, Joyce’s subsequent comments about directing the serial suggest that Warriors’ Gate marked the beginning of the end of Doctor Who as we knew it, as if Joyce himself is a kind of Tharil, able to “see” a future that the series is unable or unwilling to see or adapt to.

Taken at face value, Joyce’s statement that “I was trying to bring film consciousness to bear on TV”8 raises interesting problems. These include historical problems, given that various television directors had arguably done this over the previous two decades,9 and problems of specificity and methodology, by which I mean that the current vogue for using the word “cinematic” as praise for television drama (and the parallel habit of using the word “theatrical” pejoratively) may be problematic in terms of our understanding of television drama. These are among the many issues that are being discussed in current academic debates on television aesthetics.10 Such distinctions bring into question our own methodology when we write about television. In my description of the opening sequence above I used terms that are more slippery than I made out. I’ll stick with “tracking shots” to describe moments when the camera bodily moves, even though I know the cameras here are not on tracks: “dollies” might be safer than “tracks” (or even “crabs”, a term familiar for studio pedestal cameras). Like the commentary team on the DVD, I’ve said “dissolves” even though “mixes” would fit more comfortably with dramas recorded in electronic studios with a vision mixer working with the simultaneous recording of multiple cameras (though Joyce’s methods at times muddy this distinction). Other terms are more familiar: for cameras that don’t move from their standing position, “panning” for horizontal looks, “tilting” for vertical looks and “zooming” for changes in focal length (zooming in, we see something more closely even though the camera itself does not physically move toward what we are seeing). 1970s Doctor Who is full of zooms, particularly crash-zooms in or out, although the ins are perhaps more famous (moving suddenly from long-shot to close-up of the titular creatures from The Sea Devils (1972) for instance). I’m being anally retentive about the terminology because, as we’ll see, the production of Warriors’ Gate was accompanied by a heated debate about the place of film vocabulary in the television studio, when even the idea of distinguishing their methods so baldly from each other is problematic. Language matters, both in the words used (particularly the binary “film/not film”) and the visual language being deployed. The opening of episode one asks us to notice the latter. But the dispute between Joyce and some colleagues was partly about distinctions within these types of language.

Rather than grinding to a halt on this point, I’ll move on by reading Joyce’s comment as addressing the specific challenges of bringing this “consciousness” to bear on Doctor Who’s own specific use of multi-camera video studio practice. Like Lovett Bickford, another director hired by new producer John Nathan-Turner to help give Doctor Who’s eighteenth season (1980-81) a new look, Joyce gave the visuals a greater semantic weight. Joyce said that other Doctor Who directors were just “calling shots”, but they met their schedules (to watch The Visitation (1982) is to watch a director whose episodes will neither underrun their slot nor overrun their studio time). By contrast, Bickford (in The Leisure Hive (1980)) and Joyce struggled to achieve their aims in Doctor Who’s allotted studio time and never worked on the show again. Joyce’s “filmic consciousness” was related to the logistics of cinematic practice in a scathing memo by the Technical Manager:

The director lacks a working understanding of the methods used to make programmes in BBC television studios. His shooting ratio must be near the 10:1 level of a feature film production. He expects a 360° panorama to be continually available to his ‘hand held’ camera and the lighting and sound problems are endless. If the BBC is really interested in quality and economy, no Technical Operations’ crew should be subjected to such self-indulgent incompetence.11

The feeling was mutual: Joyce later said that it had been “a crazy notion” for him “to try to take on and distort a basically unfriendly system run by people who, if not completely intellectually bankrupt, were operating to the limits of their mental overdrafts”.12 I’m quoting these comments not to rake over old personal disagreements, nor to investigate competing claims about Joyce’s ability to schedule studio recording sessions, but because their tone shows just how strongly these views – or the discourse surrounding perceptions of the spaces of television – were felt. There were several problems – including safety concerns about the raised gantry that Joyce used, though its inaccessibility helped him to get access to the BBC’s Ikegami handheld electronic camera.

Spaces between spaces of television

But one specific dispute is worth dwelling on, a response to Joyce’s practice that was triggered by a moment in this opening sequence. The low-angle walkway shot, with its glimpse of the lighting rig in Television Centre’s Studio 6, meant “shooting off the set”, which led to complaints from some involved in the production. (Joyce’s editing notes describe the shot through the walkway as a “possible insert”, evidence of his “filmic consciousness” in one sense, as he took single-camera footage and constructed this sequence in the edit rather than through vision mixing between multiple cameras recording simultaneously.) The falling-out contributed to the loss of studio time and Joyce’s temporary sacking. Joyce complained about this “old school” attitude, and may have had a point, given that the lights could be interpreted as part of the set and this scene doesn’t involve the kind of non-naturalistic, spectacular shooting off-set we see in Dennis Potter’s Follow the Yellow Brick Road or Philip Martin’s Gangsters, when we pull back from the dramatic illusion to show the studio, the crew and the artifice.

Formally, Doctor Who was and is “naturalistic”. This was the case even when Philip Martin wrote Vengeance on Varos (1985) for Doctor Who, and ended episode one with a self-aware cliffhanger. Varos’s Governor directs television coverage of the Doctor’s seeming death, and tells his operator when to “cut it”, thereby also providing our cliffhanger. This moment draws attention to the editing and even Doctor Who’s constant references to televisuality throughout its fifty years, but it is entirely consistent with the story world and is shot on a set. It does not make us step back to consider the programme’s constructedness or the ideological workings of form in any deeper sense. (Consider this alternative: the story’s Governor and villainous Sil enter the actual BBC studio gallery, sit next to John Nathan-Turner and director Ron Jones and line up BBC studio cameras on Colin Baker.)

One obvious problem with showing the studio lights is that it looks like a mistake. But plenty of mistakes have been left in Doctor Who episodes over the years, and some of them involve wrongly showing studio lights. During a camera movement in the acclaimed The Caves of Androzani (1984), we briefly see a studio light over the top of a spaceship set. Indeed, we get a glimpse of studio lights over the top of a set in the first minute of the first episode, An Unearthly Child (1963). In Earthshock (1982), while characters are dealing with the effects of an attack by the Cybermen, viewers with their contrast turned up saw a trainee Production Manager reading the camera script, turning a page as the scene progressed. Perhaps we need a theory to deal with those moments when the extra-textual becomes stubbornly textual (rather than just expunging them for DVD releases). What do we do with them? True, we could mischievously rationalise them: perhaps some alien worlds do suffer ghostly cries of “Cue!” (rather than those moments merely being induction from floor managers’ headphones), there are unseen characters who audibly drop pencils on the floor (perhaps The Silence have moved into stationery), and the Cybermen in Earthshock are so callous as to have a time-and-motion expert following their massacre (“less talking about eating well-prepared meals, more shooting”). We could over-analyse accidental breaches in diegesis as non-naturalism. Or, to be less facetious for a moment, we could find a way of thinking about these moments in terms of aesthetics, specificity, evaluation and the display of working space. I’ve seen rushes of studio footage for many programmes and am constantly fascinated by what floor managers do in their working space, our mental space – spaces between spaces of television.

But Joyce’s “shooting off the set” has another, albeit inadvertent, significance. John Nathan-Turner voiced his suspicion that the “decrepit spaceship that was on its last legs with a crew of people who really have no interest” was Gallagher’s “appreciation of Granada television”, where he had been working. Nathan-Turner was happy that “the personal signature was completely hidden […] behind the action-drama story” (unlike in the suspected Play for Today self-expression of Kinda).13 So perhaps the lighting rig is a useful marker…

Film references

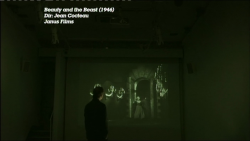

Another way of reading “film consciousness” is to think about the serial’s numerous film references. (There are also references to other forms including literary science fiction and pop videos, but I’m neglecting those – they’re discussed elsewhere, for instance by Lawrence Miles and Tat Wood.14 ) One of the most widely-discussed elements of Warriors’ Gate – something foregrounded by Gallagher in various interviews – is the influence of Jean Cocteau on its imagery and themes. This influence includes, but is not restricted to, the “leonine” Tharils coming via La Belle et la Bête (1946) and the mirror and time architecture coming via Orphée (1949). I won’t draw those influences together in a “spaces of television” concern with the television studio because Billy Smart has recently done that on the Spaces of Television website.15

So when I return to Cocteau later, it will be because connections with his films raise wider issues than just the look of this one story. In the meantime, Matthew Sweet, in his excellent Culture Show documentary Me, You and Doctor Who (2013), used Cocteau’s influence as an example of the programme’s changing audience address, becoming “high concept” and wanting to be “taken seriously”.16 Sweet stood in front of images from Cocteau and from Warriors’ Gate: interestingly given what we’ve seen of debates during the production, he views both on a large cinema-like screen rather than on a television screen which Sweet watches elsewhere in the programme. If we say that the sense of temporal subjectivity, the mirror and architecture, the framing through legs and the ship’s dysfunctional functionalism owe something to, respectively, Cocteau films listed above, Alain Resnais’s Last Year at Marienbad (1961), Robert Aldrich’s Kiss Me Deadly (1955), and John Carpenter and Dan O’ Bannon’s Dark Star (1974), we can support this through document research: Joyce requested viewings of those films in preparation. Moreover, Joyce has had an impressive career making documentaries about films and filmmakers, including Nicolas Roeg, Wim Wenders, Ken Russell’s The Devils (1971) and Stanley Kubrick’s 2001 (1968). Therefore, it’s hardly surprising that Warriors’ Gate is often intertextual, although the direction and the script don’t always agree on the key references. As the story goes on the importance of Cocteau becomes even more apparent, but by focusing on the opening scenes from episode one I’ve set myself a challenge. This sequence’s dolly shots and flowing dissolves hardly reflect Cocteau’s statements that “Except on very rare occasions, the movement of the camera cancels the movement of the subject […] Montage is style”, and that he wanted “to prevent the images from flowing” and instead “oppose them to each other”.17

But we can think about two (of the) films whose openings are similar to this one: Touch of Evil (1959) and Alien (1979). The point isn’t to problematically tick off “influences” but to think through the appropriateness of the methods for this story. Touch of Evil’s opening shot lasts three minutes. Like Warriors’ Gate it starts with a closer look at a device (a bomb), before showing it being planted in a car and then following the progress of that car, using various shot sizes and showing a range of activity, including a sweeping crane shot around buildings and dialogue spoken while walking. However, Touch of Evil brilliantly does this in one continuous, developing shot: there are no editing transitions until the explosion of the bomb triggers the film’s first cut, breaking up the fluidity of the style in an appropriately jarring way. Touch of Evil’s opening seems to be mentioned whenever Doctor Who holds a moving shot – James Chapman relates it to the Doctor and Rose’s walking conversation during Rose (2005)18 – but what’s striking about this particular long take with movement is that the mobility serves the introduction and exploration of the fictional (and social) world and builds narrative suspense (our awareness of the bomb is heightened by the casual banality of life going on unawares, as in Alfred Hitchcock’s description of suspense). The resemblance between the opening sequences of Warriors’ Gate and Alien is more clearly marked: before crew members awake from stasis, there’s a sequence of empty corridors, with tracking shots, pans and pull-focus, though not dissolves. Again movement is halted (albeit temporarily), in this case because equipment stirs into life, at which point we observe it in several static shots. Alien’s opening is one of SF’s most widely analysed sequences – film students have often been set it alongside Barbara Creed’s The Monstrous-Feminine to unpick its key psychoanalytic themes involving birth and motherhood. The opening sequence provides space for active contemplation, and a sense that there is something to be discovered. My remit here doesn’t involve tracing Alien’s influence on Doctor Who, or vice versa (by which I mean The Ark in Space (1975)’s similarity to Alien, not Alien‘s influence on, er, Vice Versa (1988) ), or more likely their borrowing from the same sources. We can guess Tom Baker’s reaction to this signposting of profundity, from his concern that season eighteen neglected its child audience, or more entertainingly from the commentary that he gave patrons at Leicester Square Odeon when he, Lalla Ward and Graham Crowden saw Alien, whose characters he found so dull that he suggested sending them after the creature to talk to it and therefore “bore it to death”.

What was ahead

So why does Warriors’ Gate start like this? Can thinking about these film references help us to “read” the story? The opening clearly has some significance, even if Joyce was wrong to see this stamping of “directorial authority” as unique. After all, Lovett Bickford (who talked about having a “particularly idiosyncratic visual style”) opens The Leisure Hive with a lengthy pan across out-of-season Brighton beach, eventually finding the Doctor asleep in a deck chair. I’m surprised that Bidmead once said that “It was full of great meaning for Lovett […] but I think at the expense of the rest of the episode”, because, as I’ve said elsewhere, “the shot establishes an atmosphere of regret and desolation in leisure and reinforces the theme of ‘doing nothing’, which comes up throughout the season and becomes the Doctor’s defence against entropy.”19 Both stories therefore open with distinctive visual movement that is halted by arrival at a character who will be particularly associated with the value of doing nothing. Perhaps Warriors’ Gate therefore opens with the visual representation of key themes. Gallagher’s novelisation is on-message for the season’s approach to entropy:

The crew were lounging and sprawling around, doing nothing in particular […] Maybe the privateer’s control areas had once been gleaming and efficient, but that had been a long time ago. Now it was badly lit and filthy, the theme colour being that of rust; any paint was streaked and aged, fixtures were held in place with tape, glass covers to screens were split and cracked. […] The garment looked unsalvageable, holed and patched.20

That sounds like the aesthetic of Dark Star and Alien, but also builds on the recurring entropic theme expressed in season eighteen that the more you keep putting things together, the more they keep falling apart…

Perhaps the visual representation of movement does a similar job. That’s possible, although it depends on what we think the movement is. Why are we seeing this? What are we seeing? We sometimes forget to ask these questions because we know so many facts: we know that Joyce set out to achieve interesting visuals, we know that Gallagher wrote an opening with the Antonine Killer attacking the ship (it’s in the novelisation), we know (from comments quoted earlier in this essay) that this sequence was typical of a complex shooting script that required a shooting ratio nearer to feature films than Doctor Who studio days. But what’s motivating the camera movement?

“Motivation” doesn’t just mean optical point-of-view shots (seeing directly from a character’s perspective), though it could. When we think about what’s motivating a camera move, or an edit, or lighting, or sound (and so on), we’d think about sources (for example, the light pouring into the TARDIS behind Biroc when he enters it, having crossed the time winds, may come from studio lights but is “motivated” by the void) or what makes us want to turn the page. When Holly runs right to climb the stairs in Harry Lime’s flat in Carol Reed’s The Third Man (1949), the camera moves right to accommodate (is motivated by) his movement; if Hitchcock pans right across Grand Central as if following two extras who have no connection to the plot, and ends up finding Cary Grant, our hero, then their movement motivated the camera’s (and our) look right. Doctor Who companions learnt to motivate a camera move or edit to see something happening (or about to happen) with the inelegant “Doctor, look –!”21 One way to think about how Warriors’ Gate is different is (paradoxically) to compare it with something similar. In episode one of The Caves of Androzani, we see Sharaz Jek up to something in his lair: again we have pans and camera moves (with more pronounced use of hand-held cameras), with dissolves. The Caves of Androzani was the first Doctor Who story directed by Graeme Harper, though his work as Production Assistant on Warriors’ Gate included taking over elements of directing (I’m choosing my words carefully…) from Joyce during the fraught studio sessions. There are more similarities between these two stories than this sequence or the same nicked-from-a-film shot through a character’s legs, though the extent to which Harper stamped his style on Warriors’ Gate, or was just as inspired by Joyce as he was by Douglas Camfield, is an issue for another time. This Androzani sequence is as atmospheric and visually pleasing as the Warriors’ Gate opening, but it’s more conventional in that it’s motivated by Jek’s movement and actions, and by our desire to know what he’s up to. It’s a conventional montage, compressing story time (and compressing a longer sequence for timing).

By contrast, it’s not immediately clear what’s motivating the Warriors’ Gate opening – at least, not until we think more thematically. (We can talk about the old Peter Wollen binaries between mainstream and “art” cinema, arguably raised by what I’ve just suggested, some other time.) Bearing in mind what I was saying about Gallagher’s themes, perhaps the machine in the opening shot is yet another device that is trying to maintain the status quo but which is creating the opposite effect. In that case, the parallel with Touch of Evil is useful: the machinery (or what it symbolises) will cause the narrative disruption – or, in the logic of season eighteen, it’s failing to restore an equilibrium that’s already long past the initial disruption. (We can talk about Tzvetan Todorov’s narrative theory some other time. I’m already suspecting that you’ll be hiding behind the settee pretending to be out.) We see people playing cards, we will see the tossing of coins.22

It seems that what motivates the camera movement and editing in the opening sequence is, simply, Biroc. We move towards walls, ceilings, barriers, testing the chance for escape. Associating Biroc, the character who can’t move, with this restless, dynamic movement may, on first viewing, seem counterintuitive (if we persist in seeing it as physical space). As I’ve said, the movement stops when the camera reaches Biroc, as a thematic leap – the movement stops because of the importance of “doing nothing”. But there are (at least!) two tensions in play here. Firstly, the dynamic style has accompanied nothing happening, but as the camera stops and we see the character who will do nothing, things start to happen (the story). Secondly, Rorvik is having trouble getting Biroc to visualise, but perhaps the first few minutes of the story are all about visualisation, Joyce’s and Biroc’s. It would be problematic to describe the first few minutes as point-of-view, optical or otherwise, but Gallagher’s novelisation, near the end, offers us a window (sorry, it’s Warriors’ Gate – a mirror?) into the accomplished visual unity. We’re hearing about Biroc’s “remarkable” achievement “as he’d lain in the shackles on the privateer’s bridge”:

As the Doctor had only just realised, Biroc had managed to glimpse as a unity the events that would follow if the privateer and the TARDIS were to be brought together at the gateway. There had been no randomness in his actions, and no indecisions in his failures to act. When Biroc watched and did nothing, it was because he already knew what was ahead.23

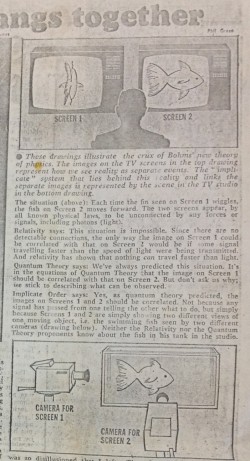

The image also reminds me of this Sunday Times article, one of the documents the script editor sent to Stephen Gallagher – explaining implicate theory and how the universe hangs together, explained through the imagery of TV screens. Biroc is tele-visualising.

The refreshing discovery of the magical in the real

If the first three minutes of episode one relate to “what’s ahead” in their testing of barriers and boundaries, we should think about where those occur elsewhere in the story, which mercifully means that I don’t have to ignore Cocteau quite as much as I made out earlier. The two biggest borrowings come in Biroc’s appearance (La Belle et la Bête), the mirrors and colour/black-and-white (from Orphée and Le testament d’Orphée (1960)). Again, the well-knownness of these facts doesn’t make them any less odd. These films had a problematic, contested place in the French film canon, and their place in the list of films that Doctor Who fans have heard of is even more odd. However, inspired by the visualisation of unity in the sequence I’m discussing, I’m surprised to find a few points of contact. Orphée was itself a reworking of myth, which had been a big thing in Doctor Who in the late 1970s. Cocteau’s description of Orphée’s audience members returning to the cinema several times has pleasing parallels with this serial’s reputation: “a book has to be read and re-read before it comes to occupy its rightful place”.24 David Thomson wrote that Cocteau found in the cinema “a useful image of his lifelong dream of the poet’s brave delaying of death, and of the refreshing discovery of the magical in the real.”25 The delaying of death is vital to season 18 – the philosophical, poetic escape from season 18’s determinism comes in season 19’s Castrovalva26 – and the mirrors of Warriors’ Gate echo Cocteau’s boundaries which test, in Thomson’s phrase, “the poet’s need to believe that he can pass through”. Okay, in scenes like the mirror entry “copy” might be more accurate than “echo”: Doctor Who often rips off bits from films, but it’s very Warriors’ Gate to mirror a mirror. In “the actual transformation of his films, especially the vat of mercury mirror in Orphée, the elision of real and fantasy is marvellously achieved”, making it according to Thomson “Cocteau’s greatest achievement, in which the poet at last transcended himself.” The elision of real and fantasy, the combination of the magical and the real: to misuse Thomson and Cocteau a little, might we find the essence of Doctor Who, or at least the fetishisation of the real in John Nathan-Turner’s first year? To my knowledge Cocteau never made a film about a “Yeti on the loo in Tooting Bec”, but the formal and narrative features raised by that phrase find their equivalent in Cocteau’s insistence, on La Belle et la Bête, that cinematographer Alekan avoided “technical virtuosity”. One last bit of my admittedly glib paralleling of Doctor Who and Cocteau: Thomson observed that Cocteau set out to make La Belle et la Bête as “a film that would stir adults” but “along the way he discovered the child’s imagination, too. So it’s an extraordinary and very encouraging fusion of pictures for kids and the surrealist art tradition […] What keeps the film modern and dreamlike are things like Belle’s way of moving without effort or friction, and the very adult, Freudian understanding of symbols. Children at the movies require no special care or condescension. They expect genius.”27

From An Unearthly Child to The Day of the Doctor

Did Joyce, like Biroc, know “what was ahead”? A lot of the terms from earlier in this essay – authorial, enunciative camerawork, stamping directorial authority – could describe post-2010 Doctor Who under Steven Moffat. But then it could also describe Waris Hussein’s work on the very first episode, An Unearthly Child, in 1963. Indeed, Doctor Who starts with a camera exploring space and raising questions about “motivation”: we approach I. M. Foreman’s junkyard on Totter’s Lane partly in sympathy with an anonymous policeman’s oversight of his beat, but the opening of the gate and the movement toward the police box itself are motivated not by narrative but by mystery – why is this police box here, what is that humming noise, why does this seemingly innocuous thing seem mysterious (of course the uncanny will become a signature of Doctor Who). Doctor Who has returned to Totter’s Lane several times over the years, but arguably only in the recent fiftieth anniversary trailers has the style of that opening been directly referenced in its treatment of the policeman, the movement, the mystery.28 If The Day of the Doctor or future Moffat scripts return to the lovely unresolved details of that junkyard – and the painting that the Doctor, playing for time, expresses surprise at not having seen before is particularly inviting for timey-wimey action – it will be appropriate. For instance, it would remind us of the spaces of Hussein’s direction, the subjective (but not optical point-of-view) shots of Susan to cover Ian and Barbara being on another set during flashbacks, the mixing between text on the TARDIS and at Coal Hill School. An Unearthly Child does not establish a house style, as its approach to studio space and narrative time is mirrored only sporadically through the next 26 years, but it sits more neatly in the lineage of Moffat’s Doctor Who than many episodes – The Crimson Horror being a choice example of camera-as-author and the incorporation of text into narrative space (one of the devices that were innovated by series like Teachers in the early 2000s). The narrative complexity and visual tropes of Moffat’s Doctor Who make Warriors’ Gate a more natural predecessor than a lot of twentieth-century Doctor Who – and it’s surprising to see a wireframe TARDIS of the sort visualised by Biroc on the Save The Day website at the moment – but Warriors’ Gate also shares more with Hussein’s approach than you might think.

Dreaming in the television studio

But if Joyce “knew what was ahead”, it wasn’t so much in terms of Doctor Who as in terms of the industry. By distinguishing between himself and those directors he thought were “calling shots”, he echoes the Film Studies distinction between an auteur and a metteur-en-scène. I’ve talked about Doctor Who’s directors in relation to this elsewhere, so I won’t repeat myself,29 because my point here is just that Joyce’s critics also used this same distinction. The Technical Manager’s point (above) is less television versus cinema as a question about different modes of television. Joyce’s critics said that he was a “serious” filmmaker who’d worked on Play for Today and was frustrated by different conditions on series. Perhaps, but a few Doctor Who personnel worked on Play for Today in Joyce’s time, including David Maloney, John Gorrie, Frank Cox, Gerald Blake, Fiona Cumming and Graham Williams. The BBC rotated staff, as revealed positively in the presence of some astonishing directors of photography (“film cameramen”) and film editors on Doctor Who, and, according to Joyce and others, negatively in terms of non-drama-specialist studio camera crews. Joyce complained about working in the multi-camera video studio, saying that (all) television drama would move onto film, onto single camera (I stressed “all” because there had been lots of all-film dramas at the BBC before the 1980s). Joyce of course has a point: Film on Four, Screen One and others mark the 1980s as the period when film came to dominate drama output and the days of multi-camera video drama were numbered. As iconoclastic as Joyce sounds (he saw Barry Letts in particular as yesterday’s man), I doubt he’d claim to be saying anything new. Ken Loach and Tony Garnett fought rules on studio allocation in the 1960s to work entirely on film. There were plenty of slots for all-film drama in the two decades preceding Joyce’s battle. In 1976, Dennis Potter predicted that plays “will soon all be done on film, and it’ll be a director’s medium like the cinema. It only remains an author’s medium at the moment because of British anachronisms”.30 In terms of depending on multi-camera studios, Doctor Who stayed rooted in those anachronisms for much longer than other forms. Listen to Peter Davison-era DVD commentaries and you hear about the inevitable, inescapable flaws of multi-camera studio drama: theatrical, proscenium-arch presentation, overlighting, a lack of atmosphere. Therefore, they and various fans say, all drama looked like Doctor Who then.

But they’re wrong. Fluidity, mobility, depth of field, compositions that are pleasing and expressive: there are many studio-based dramas that feature these qualities, from big serials (Pennies from Heaven (1978)) to one-off plays (among other examples in this period, Alan Clarke and David Leland’s Psy-Warriors (1981)). These qualities are rare in Doctor Who (but you should see Miles and Wood for a list of the series’ unusual auteurs31 ), and we often end up with front-on theatrical scenes, despite those features being challenged elsewhere. For example, in 1960, Lena O My Lena shows the desire to move cameras into the performance space, the kind of thing Harper does; indeed, as Miles and Wood put it, one of Harper’s signatures is “the foregrounding of the character almost as a character”.32 Indeed, the movement in Lena, O My Lena is comparable with the work being done by Hussein. To be fair, some dramas had more time and money than Doctor Who. The production problems on Terminus (1982) say more about the slashing of an already unrealistic studio schedule than about Mary Ridge’s vision. But a number of directors made distinctive work in comparable timeframes in multi-camera studios (I’m not downplaying the impact of the added complexity of Doctor Who‘s effects work, though a number of directors outwith Doctor Who also faced technical challenges). Of course there are clear problems with the way the television studio is used in various Doctor Who stories of the 1980s, problems that justify the complaints of the Davison commentary teams – but they’re not inherent in the form (indeed, they are quick to exempt Harper from criticism.) I’m also not denying that film did come to dominate drama from this period onwards and some programme makers fought to avoid video. (I mentioned Clarke, who made some great studio dramas, but he worked entirely on film after 1984 and was not disappointed to be doing so.) However, it’s wrong to say that the television studio neatly gave way to film at this point and that that was inevitably “progress”. Studio drama persisted beyond the 1980s and the movement away from it was contested, not least by Don Taylor (who also takes us back to An Unearthly Child in that he turned down the chance to be Doctor Who‘s first producer), who argued that, if you’re looking for the “kind of television drama that can be described as indigenous, in the sense that it is not available in any other form”, you should look at studio drama, because “Studio television is the only genuine and irreplaceable TV drama.”33 (Without getting into debates that belong in another essay, obviously there were plenty of programme makers who disputed this.34 )

There is an alternative history that the often-technologically-experimental Doctor Who could have played more of a part in. As late as 1982, the BBC’s Head of Plays (Keith Williams) cited Psy-Warriors as an example of how studio drama need not be a backwards step but a way “to put new energy and imagination” into drama (“the television play lies somewhere in that direction”), while the BBC’s “commitment to studio is substantial, both in terms of building and equipment, and in the staff we have”. (My book Alan Clarke goes into many of these issues and has been reissued in paperback and everything.)35 From John McGrath and Philip Saville to Dennis Potter and Philip Martin, the studio had provided a space for distinctively non-naturalistic drama, all the more attractive to programme makers because the public felt comfortable with studios as the dominant form of naturalism (for instance, soap and sitcom). Being able to play with those expectations explains, for instance, why Potter wanted the hospital scenes in 1986’s The Singing Detective to be shot in the video studio, but was talked out of it. By 1986, Doctor Who was seen by many at the BBC as a product of the past, and its production methods were part of that view. The decline from the huge celebration of the brand at Longleat in 1983 to attempted cancellation in 1985 has more sources than there’s space to go into here, but changing discourses on the studio’s place in definitions of the televisual played a part. Warriors’ Gate shows that things could have been different.

In the opening of Warriors’ Gate, Biroc tests the space around him, and perhaps Joyce does the same: exploring the studio. Whether a space for vibrant studio drama that wasn’t taken up, or a space for tatty multi-camera anachronistic-SF-in-the-age-of-Star–Wars, the space seen by Biroc/Joyce may be witnessing the end of Doctor Who as we know it, or even realising that the end has already taken place, like the heat death by which the Doctor is confronted in season eighteen. Even if we accept that Doctor Who’s fate was connected with failing to deal with the aesthetic tensions identified in the battles faced by Bickford and Joyce, we should be more careful than to automatically blame the workmen’s tools. Joyce described his approach as “filmic”, but as we’ve seen it’s problematic to separate film and television approaches in essentialist terms.

By the end of Warriors’ Gate, when Romana walks away in colour through a transitional space represented by a monochrome photograph, it’s a filmic reference and a televisual achievement. This is a story in which the studio is put to often exciting use. While Full Circle was being broadcast, John McGrath’s The Adventures of Frank made experimental use of video effects on BBC1. While The Keeper of Traken was being broadcast, Philip Saville’s The Journal of Bridget Hitler had characters interacting distinctively with photographs as part of its interrogation of, and play with, subjective historical testimony.

Therefore, to say that Warriors’ Gate is of its time is to simultaneously regret its restrictions and cherish its modernity. The studio is the perfect place for the opening of Warriors’ Gate: a transitional, liminal space, full of tensions. Past (a form of drama from which Joyce and television wanted to escape), present (the video studio’s present-tense immediacy) and future (or lack thereof). Lighting rigs and mics in shot, confinement and boredom, boundaries and dream time. At the end of the sequence, on a (television) screen, we see the TARDIS – visualised, dreamed.

Originally posted: 23 November 2013.

Updates:

24 November 2013: minor corrections to expression; reinstated accidentally omitted Taylor material.

5 December 2013: clarified one Miles and Wood reference; added foregrounding of camera quotation; clarified sentences surrounding the latter.

This piece combines, rewrites and extends two previous pieces:

‘What Was Ahead: studio as gateway in Doctor Who – ‘Warriors’ Gate’ (1981)’, a conference paper delivered at the University of Reading in the conference Spaces of Television: Production, Site and Style (September 2013).

‘Opening the Gate’, an article in the fanzine Plaything of Sutekh, Issue 2 (Winter 2012).

Thanks to John Connors. Plaything of Sutekh is available here.