by DAVID ROLINSON

Four parts. Writer: Stephen Gallagher; Producer: John Nathan-Turner; Director: Paul Joyce

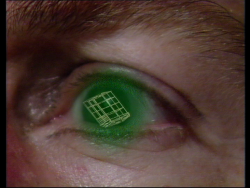

Warriors’ Gate was a visually inventive, conceptually ambitious and idiosyncratic Doctor Who serial, but also a fraught one for Paul Joyce, its director.1 The disagreements behind the scenes have been well documented, and are often discussed as a marker or consequence of the serial’s ambition.2 I’ve researched this serial in the BBC Written Archives Centre production file on Warriors’ Gate and the archive of writer Stephen Gallagher that is held by Hull History Centre,3 studying everything from multiple script drafts and notes on script meetings through to the specs for the set’s timber framed gimbal mirror and a list of supplementary payments for overtime and wig fittings (at productive moments in these archives it was of course difficult not to declare that “I’m finally getting something done!”4 ). However, this essay is not a blow-by-blow production history but a discussion of Joyce’s direction: partly showing how Joyce’s approach helps to convey the serial’s ideas, but mainly showing how debates about the future of Doctor Who’s production methods and the spaces of television circulated around Warriors’ Gate.

Doctor Who: Warriors’ Gate, tx. BBC1, 3-24 January 1981. ↩

See The Dreaming, a documentary on the Warriors’ Gate DVD (2009). The emphasis on creative ambition and vision differs from the ways in which other notably fraught Doctor Who productions have been discussed, such as Nightmare of Eden (1979). ↩

The BBC has made some basic documentation available online, including the Programme-as-Completed file on Warriors’ Gate. ↩

This is a line spoken with some intensity by the character Rorvik at a crucial moment. ↩