by FRANK COLLINS

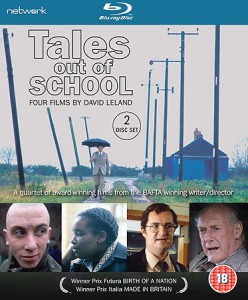

Writer: David Leland; Producer: Margaret Matheson; Directors: Mike Newell, Edward Bennett, Jane Howell, Alan Clarke

Because this site’s editor, Dave Rolinson, was involved with the Tales Out of School DVD (writing its 12,000-word booklet), it seemed fairer to ask a guest writer to review it: so here’s a review by Frank Collins, who writes the excellent, highly-recommended film & TV review blog Cathode Ray Tube. Many thanks to Frank for letting us reproduce this review.

David Leland’s quartet of dramas from 1983, under their original umbrella title of Tales Out of School, gets a very welcome release from Network this month. All four films, Birth of a Nation, Flying into the Wind, RHINO and Made in Britain, were commissioned by Central Independent Television, the ITV franchise that emerged from the restructuring of the original ATV, and were produced by Margaret Matheson, who had become Controller of Drama after a successful if controversial time at the BBC where she had produced Alan Clarke’s banned television play, Scum. After a steady career as an actor during the 1960s and 1970s, Leland’s reputation as a writer willing to tackle socially sensitive subject matters grew through his work in 1981 on Play For Today, on Psy Warriors and Beloved Enemy.

Both plays had also brought him into contact with director Alan Clarke whose work, radical and realist in tone, had become fiercely political and controversial (he had directed the banned production of Scum for Matheson and the later cinema version). Their paths would all cross again on the production of these four films, with Clarke directing the Prix Italia award-winning Made in Britain, the final film of the quartet. As Leland outlines in both of the excellent documentaries that supplement this release, he had been concerned with the structure and power of mass education for some time.

Tales Out of School firmly belongs in the tradition of social realist drama that stretches back to the work of Loach, Garnett and Sandford on Cathy Come Home in 1966, and was contemporaneously in 1982, in what was seen as a very politically and socially divisive period, perhaps then exemplified by Bleasdale’s recent Boys from the Blackstuff. In his four films Leland traces a number of still contentious ideas about education, questioning the institutional roles and teaching practices within schools, the power of the education system, the law and the judges and courts that dispense order and structure within a complex web of relationships between pupils, teachers, parents, education officers, the police, magistrates and social workers. By doing so he asks us to consider how these institutions, and schools particularly in the first two films, shape the futures of young people, perhaps through a repressive and conformist curriculum that is more concerned with processing young minds for the job market above all else. This also brings in themes about identity, marginalisation, oppression and race, class and gender.