by DAVID ROLINSON

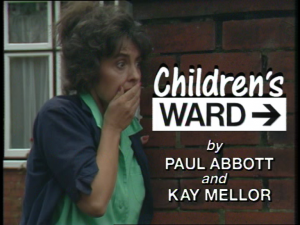

These days, teatime ITV means repeats of Midsomer Murders or reality formats so recycled that their pitches were delivered in a green caddy. But Children’s Ward is a reminder that this slot used to house children’s programmes, including three great drama series that started in 1989: Press Gang (on 6 January), Children’s Ward (on 15 March, after a 1988 one-off) and Byker (Byker!) Grove (on 8 November). Given that the 1990 Broadcasting Act entrenched deregulation, it’s tempting to see these shows clinging to pre-1990 public service values, and aiming to give children the same range of programming that was available to adults.

What would ITV do now to have shows in the same week written by Paul Abbott, Kay Mellor and Steven Moffat? That happened for the first few weeks of Children’s Ward’s run (Press Gang Mondays, Children’s Ward Wednesdays). Welcoming an Ofcom review of children’s programming, Mark Wright at Television Today argued that, despite there being numerous digital channels for children, there aren’t many “original, home grown shows that nurture not only young and upcoming talent, but bring new audiences” to television rather than encouraging kids to “sod off to the Internet”.1 As Wright notes, many of Children’s Ward’s alumni are now “among the premier drama writers in the country”: Abbott, Mellor and (from later seasons) Russell T. Davies, Matt Jones, and Sally Wainwright.

Mark Wright, ‘ITV denies the talent of the future…’, The Stage and Television Today, 14 February 2007, accessed here. ↩