by DAVID ROLINSON

Writer: Steven Moffat; Director: Adam Smith

For me, Doctor Who literally is a fairy tale. It’s not really science fiction. It’s not set in space, it’s set under your bed. – Steven Moffat1

If you look at the stories I’ve written so far I suppose I might be slightly more at the fairy-tale and Tim Burton end of Doctor Who, whereas Russell is probably more at the blockbuster and Superman end of the show. – Steven Moffat2

Here are a few thoughts on the ideas at work in The Eleventh Hour, the first episode of the 2010 season of Doctor Who. It’s not a straight ‘review’, because there are enough of those on the internet already. But it’s also not the type of researched essay you expect from this site, because I’m interested in the episode’s ambiguities and the thoughts circulating in my head after seeing it, and don’t want to re-watch the episode to death or wait until the end of the season when some of those ideas will have been resolved. This piece will discuss the ideas relating to the ‘storybook quality’ that new lead writer Steven Moffat has talked about3, think about how style and imagery support characterisation and theme, and work out why my mind has made associations with the classic Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger film A Matter of Life and Death (1946). This piece contains spoilers, and, unlike other essays on this site, you will need to have seen the episode to know what I’m talking about.

Steven Moffat, quoted in Gareth McLean, ‘The man with a monster of a job’, The Guardian, Media Guardian, 22 March 2010, p. 5. ↩

Steven Moffat, quoted in BBC press release, available at http://www.bbc.co.uk/pressoffice/pressreleases/stories/2010/03_march/19/doctor_who2.shtml. ↩

McLean, ‘The man with a monster of a job’, p. 5. ↩

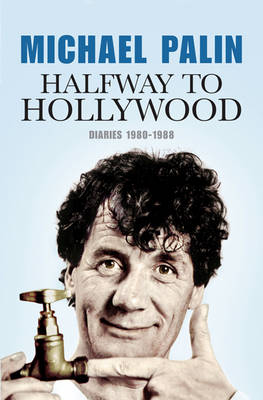

g, production, post-production, critical reception and awards nominations (plus Palin’s unusually scathing comment that the London Film Festival were ‘Snobs’ to pass on it).

g, production, post-production, critical reception and awards nominations (plus Palin’s unusually scathing comment that the London Film Festival were ‘Snobs’ to pass on it).